Because it’s there! That’s what George Herbert Leigh Mallory retorted when a reporter asked him why he wanted to climb Mount Everest.

Because it’s there! That’s what I say when people ask me why I adapted a classic Vest Pocket Kodak camera to fit my Canon 7D digital SLR. At least, that is the short answer.

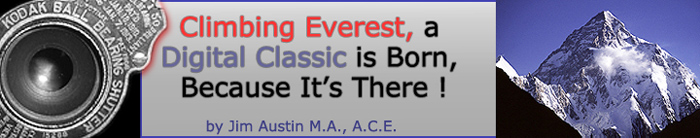

Top: Mount Everest

Middle: Mallory (left), Irving (right)

Bottom: In camp wearing oxygen

A more persuasive reason is because 2011 is the year of the Digital Classic, an emerging movement in Do-It-Yourself digital photography. Before we see how well a 1910 camera can work on a 2010 digital SLR, let’s get some background and relive a fateful Everest expedition to see how a Vest Pocket Kodak got lost on the mountain.

Part One: The Kodak That Crossed the Khumbu

Think of climbing the highest mountain in the world. It’s equivalent to five and a half miles or 2900 flights of stairs. You have to cross the Khumbu ice fall, a frozen trap of wide chasms, falling ice, and it has a reputation as being a climber’s graveyard. In bad weather, it can take a lifetime, and a life, to climb Mount Everest.

George Mallory was undoubtedly photographed by his climbing partner, Andrew Irving, when they crossed the Khumbu with Irvine carrying a Vest Pocket Kodak. Did they also make photographs on the top of Everest? That is a mystery, because no one knows if the two British climbers made it all the way to the summit.

Andrew Comyn Irvine, a 22-year-old engineer who learned to ski just months before the expedition, climbed alongside Mallory. The men took oxygen bottles when they both left camp at 26,300 feet, climbed another two thousand feet up, and vanished on the northeast ridge of Everest on June 8th, 1924.

Trying to gauge the weather on Everest is a little like trying to predict how many steps you will take in a day; taking their final steps, Mallory and Irvine disappeared in a deadly blizzard. Did Irvine’s Vest Pocket Kodak survive? Can its film be recovered and developed? No one knows.

The last person to see Mallory and Irvine alive was the expedition’s oxygen officer, geologist Noel Odell. His diary entry reads: “At 12:50 saw M & I on ridge nearing base of final pyramid.” Odell saw Mallory and Irvine just 800 feet below the summit. Although Conrad Anker found Mallory’s body in May 1999, and Irvine’s ice axe, Andrew Irvine’s body and his Kodak camera are still missing.

Part Two: A Digital Classic Travels 100 years in Time at the Speed of Light

Like Andrew Irvine, I photograph with a Vest Pocket Kodak. Unlike Irvine, I live in the digital age, so I am not limited to film.

My adventures with it just started this year when my boon companion Richard C. Giddings gave me his beautiful 2½ inch by 4¾ inch Kodak. I was enthralled. Opening the folding cloth bellows and freeing the ball-bearing shutter and lens, I was also curious to learn more about the compact Kodak–time for a web search.

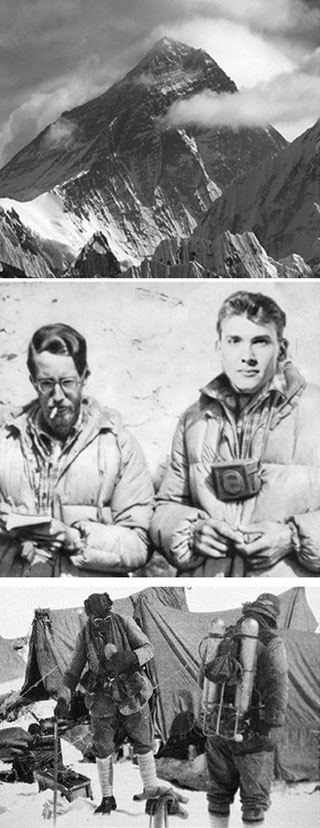

An eloquently engineered design, the Vest Pocket Kodak’s folding cloth bellows smoothly extends from its metal alloy body. The lens has a wide open f/7.7 aperture and a ball-bearing patented shutter with four speeds: 1/25th second, 1/50th second, Bulb, and Time Exposure. Some models are called “autographic” because their film type, A127, lets you autograph or write notes onto the paper backing of the negative with a metal stylus that you put through a metal flap on the camera back.

Kodak advertisements of the time said the Vest Pocket was: “As small as your notebook and told the story better” and was: “mechanically as right as a full-jeweled watch.” Kodak made the Vest Pocket camera series from 1912 to 1926 and it was a best seller. In part, that was due to the film.

I wondered what kind of film was used. Kodak’s savvy marketing strategy was to release a new film with their Vest Pocket model. Their 127 film, loaded through the rectangular metal side of the camera, made excellent black and white prints, color prints and color slides. This sleek, quick camera and film format made the Vest Pocket Kodak smaller than most 35 mm cameras and gave you eight 1? X 2½ inch exposures per roll. These were big enough to make contact prints. Prints that were 3¼ by 5½ inches cost about 15 cents. With the “super-slide” 127 color slide film, you could develop and project a slide that was larger and more brilliant than a 35 mm slide, at a 63 mm size.

The Vest Pocket Kodak was affordable. In 1912 you could buy a Vest Pocket Kodak for $6.00 or pay $10 to buy one with a Kodak anastigmatic lens. (An anastigmatic lens is able to form a pinpoint image. Its opposite, a lens that is astigmatic, has a defect such that light rays coming from a point do not meet at a focal point so that images are less sharp.) During WWI, the model was a hit with soldiers overseas because it took sharp pictures and could be carried in a pocket under a uniform.

After more on-line searching, I found a source for Vest Pocket film. Dick Haviland, a retired speech pathologist, has for many years hand made 127 films from combining salvaged spools and custom-printed backing paper. He sells these through on-line retailers. When I emailed Mr. Haviland, he called back within an hour and enthusiastically told me how to check for light leaks in the bellows of the camera and suggested using liquid black electrical tape to repair any leaks.

© 2010 Jim Austin All Rights Reserved.

Part Three: Birth of a Digital Classic…Because it’s there!

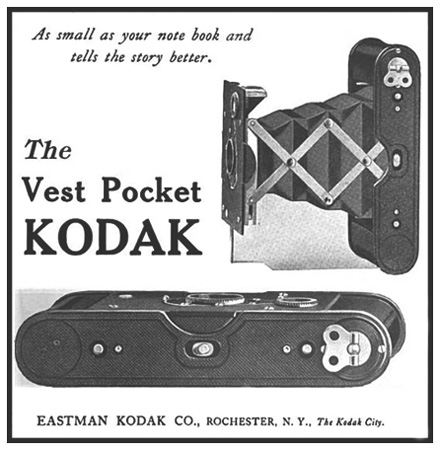

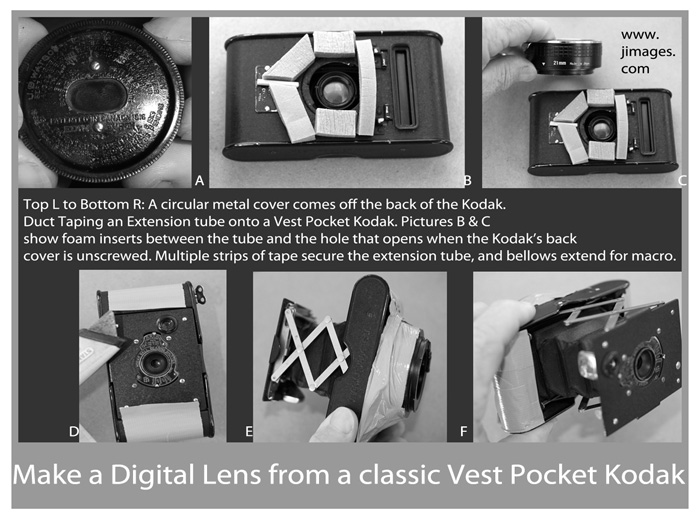

After talking to Mr. Haviland, it dawned on me that I could use an extension tube to join the Canon and the Kodak if I could remove the circular plate from the back of the Kodak. The Vest Pocket Kodak could become a lens for my digital camera. This idea was familiar to me, as I often adapt Nikon lenses to my Canon mount. My tool kit was teal-colored duct tape, an Exact-o knife, a 21 mm manual extension tube with the Canon EOS mount, and some small pieces of weather stripping foam. I taped the Vest Pocket Kodak to the extension tube and then mounted the tube to my Canon 7D digital SLR. I wondered, “Will this baby work?”

Mounted on the 7D, the Kodak’s anastigmatic lens acts like a medium telephoto. Setting the shutter to T with the aperture wide open to “Near View Portrait”, the Kodak’s small metal shutter worked flawlessly. The 7D’s exposure wizardry takes over, just as it does with any lens, but without auto-focus or aperture metadata information. Macro photographs are fun with the Vest Pocket and 7D; the Kodak lens becomes a macro telephoto when I extend the bellows.

Just in case my duct tape seal gives way, to prevent the Kodak from falling to the ground, I tie a safety line from the Kodak to my camera strap, using a seafaring bowline knot in honor of my sailor friend Mr. Giddings.

Why? Because it’s there!

© 2010 Jim Austin All Rights Reserved.

1910 Meets 2010: Live View and a Vest Pocket Kodak with extended bellow gives you a Macro/LOMO lens.

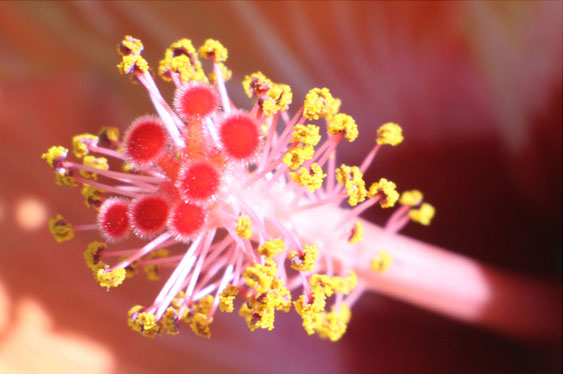

Making photographs with this digital classic is Fun–Damental photography. The picture is the thing. Sharpness, color accuracy, and exposure are not important. The subject appears – I extend the bellows to focus – and then release the digital camera’s shutter button in Program Mode. The 7D/Kodak hybrid creates lively conversations with other photographers, who ask me, “Why?” Well, because it’s there!

© 2010 Jim Austin All Rights Reserved.

Unsharpened and uncropped macro photograph taken with Vest Pocket/7D.

Original file 12.8 mb, 2592 by 1728 pixels

There is another reason. Economic hard times make photography even more expensive for many of my students. Do-It-Yourself projects in photography that can save money are popular now.

Also, as major makers release new designs, we’re moving back to classic camera designs, such as Fuji’s APS-C Finepix X100 digital camera, whose form and function resemble a 1930’s-era Leica only with digital capture.

Vest Pocket Kodak cameras are easy to get. They go for about $10 -$40 on eBay and even come in green-colored and art deco models. For those who cannot afford brand new camera gear, adapting a classic to your digital SLR saves money and returns you to a simple, direct way to get joy from your photography.

© 2010 Jim Austin All Rights Reserved.

Photos taken with the Vest Pocket Kodak camera joined to the Canon 7D digital SLR camera.

© 2010 Jim Austin All Rights Reserved.

© 2010 Jim Austin All Rights Reserved.

By Jim Austin M.A., A.C.E.

Mr. Austin is grateful to Richard C. Giddings, Dick Haviland, Apogee Photo Editor Marla Meier, and Bentley E. Smith for their help making this article possible.

Leave a Reply