Every generation has escapist media. When I was a kid, instead of Indiana Jones, the Saturday afternoon matinee at the local movie theater was often a Tarzan movie. To impressionable youngsters like me, these films and movies were an escape from the boredom of schoolbooks, transporting us to exotic realms and vicarious adventure.

Even at the time, most of us realized that the Tarzan flicks were pure hokum, probably filmed on a Hollywood backlot instead of Africa. But it didn’t matter. They fired the imagination and, in my case, sparked enough interest to pursue many books on the subject of exploration and rare and unusual animals. Many a night I lay curled under the bed covers reading by the light of a dimming flashlight long after the turn out that light and go to sleep edict had been issued. Four decades later some of those adventure books had great influence on my own book on mountain gorillas and on my photographic explorations into the realm of orangutans as well.

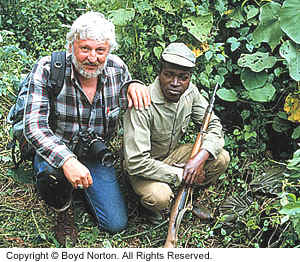

When my book The Mountain Gorilla was nearing publication in 1990, things were relatively peaceful in Rwanda and Zaire. I had made several visits to Rwanda and one to eastern Zaire in the course of getting photographs and doing research for the book. My travels there took place in 1988, 1989 and early 1990. Here, with one of the Virunga National Park rangers, we were just departing from a visit to the family led by Rugabo. This was my first trip to the region, in February 1988. By September 1990 when my book was due off the presses, civil war had broken out in Rwanda. I didn’t get back until 1994 when there was a lull in the fighting. However, only five weeks after I left from that visit, the incredible mass genocide occurred in Rwanda, leaving nearly 1 million people dead.

I shot this photo of the Muhabura Hotel in Ruhengeri during my ’94 visit to Rwanda. This is the room where I had stayed during my visits in 1990 – riddled with bullets. Little did I know that only weeks after my visit here one of the most incredible massacres in history would occur. The Hutu extremists responsible for those killings were eventually driven out and fled into eastern Zaire. However, only a little over a year ago Zaire underwent its own civil war and today this whole region is in a state of political turmoil.

What does this mean for the mountain gorillas? Serious problems. First of all important research on mountain gorillas, carried out by the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund, has been curtailed. The Karisoke research center itself has been destroyed and vandalized. Second, tourist income from visits to the gorillas has virtually stopped. In Rwanda alone, before the civil war, gorilla visitation provided a huge amount of income for this poor country. Because these animals were such a large economic asset, there was great incentive to ensure their protection.

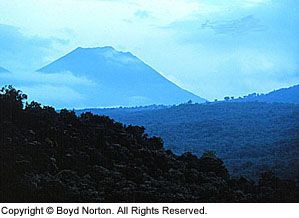

This is Mount Muhabura, 13,540 feet in elevation, one of the Virunga Volcanoes that form the border between Rwanda and Zaire. In these mist shrouded forests clinging to the slopes of these volcanoes are the last remaining mountain gorillas.

There are two national parks that preserve this habitat: Volcanoes National Park in Rwanda and, adjoining it, Virunga National Park in Zaire (now called the Democratic Republic of the Congo). Within these reserves there are an estimated 320 mountain gorillas. About 100 kilometers away in southern Uganda is the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest Reserve which has another 300 or so mountain gorillas. There has been some recent controversy as to whether the Bwindi gorillas are, in fact, mountain gorillas or a separate subspecies. Regardless, the fact remains that there are only a little over 600 of these animals left in existence. (The lowland gorilla, found throughout the forests of the Congo Basin, are much more numerous and, at the moment, are not as threatened as the mountain gorillas.)

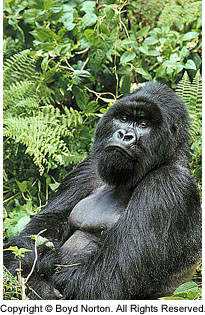

Mrithi, shown here, was the silverback leader of Group 13. During the work on my book, I made a number of visits to Mrithi’s family and I developed a strong kinship to him and to the members of his group. They were always relaxed in our presence and I felt privileged that they had allowed us to visit. We used this shot of Mrithi on the cover of my book. And because of the special attachment I had to he and his family, I was outraged when I learned that he had been shot and killed by Rwandan army troops in 1992. These “soldiers” (13-14 year old kids with AK-47s) had not been briefed on the existence of gorillas in the forest. On patrol they surprised Mrithi. He let out a warning scream (he had never been known to charge anyone). The troops panicked and started shooting. Mrithi was killed instantly. It’s fortunate that other gorillas weren’t hit.

Before visiting mountain gorillas, guides warn that you should never make eye contact with the silverback. Presumably this represents a threat to their dominance and may result in aggressive behavior on their part. I made eye contact often with Mrithi. It was hard not to. He never took offence. In fact, I often felt that there was silent communication between us. Or maybe he was just studying us, trying to figure out what these bipeds are all about. He may have come to some profound conclusions about our species. Now we’ll never know.

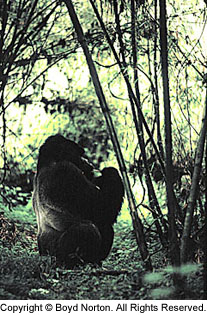

This is Mrithi feeding on bamboo leaves, a favorite food. Gorillas are vegetarian, feeding on a variety of plants: nettles, lobelia, bamboo (especially the shoots), wild celery, and vine called gallium, and sometimes certain mosses and lichens. In a typical gorilla day the family awakens at dawn (gorillas build night nests of bushy branches for mattresses). Often it is cold and misty in the dense forest. They feed leisurely, moving slowly through the forest. Midmorning is break time. Adults often snooze while youngsters, like all youngsters, take advantage of dozing adults to roughhouse and play. Mountain gorillas are sun worshippers. On those rare occasions when the sun breaks through the clouds, the whole family will find a clearing and stretch out to bask in the warming rays of sunlight (Pass the sunblock, dear.) The remainder of the day is more leisurely feeding. Food is everywhere. No TV, no phones, no crime, no hassle with jobs and the complexities of modern society. The only thing they need to fear is Homo sapiens, a species that hasn’t figured out how to live peacefully.

This is the toughest environment I’ve ever had to photograph in: dark, overcast skies, swirling mists, thick, gloomy forest, and animals that are nearly coal black in color.

Basic exposure? F/2 at two days!

There were times, when I was working on the book, when I had to give up on getting any photographs. Particularly those times when the gorillas were in very dense undergrowth with heavy forest canopy above and dark clouds above that. Ah well, it gave me time to catch up on my notes.

I used Leica cameras and lenses for 1.) their ruggedness and reliability (even in pouring rain) and 2.) the optical superiority. Most of the pictures for the book were done using the 70-210mm zoom wide open. And at maximum aperture, the Leica zoom was far better than any other zoom lenses I had tested.

At the time, the only decent higher speed film available was Kodachrome 200. I used a lot of it. And on many occasions I had to push it to 500. It did a good job, but I’d love to use the new Ektachromes today – E100S and E200 that push beautifully one and two stops.

Tripod? You gotta be kidding. Often I was standing on matted down vegetation – layers of it. A tripod resting on this mass would bounce up and down with the slightest movement by anyone nearby. Same thing with a monopod, though it was often easier to get it to rest on solid ground. Besides, when feeding, gorillas always move around in the undergrowth. You had to be ready to move and to shoot quickly when the opportunity presented itself. Most of my shots were hand held, sometimes braced against a tree if one was available nearby.

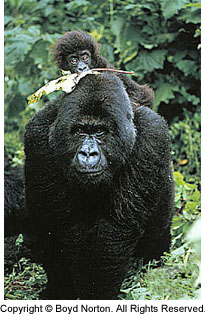

This female and youngster were a part of Rugabo’s family in Virunga National Park (Zaire). I made this photograph on my first visit to the region. Youngsters 3 months and older ride on momma’s back – until they’re too big and heavy to do so comfortably. A very small baby is carried by the mother by clutching it to her stomach when walking. The leaf was probably the baby’s plaything.

Gorillas are quadrupedal, walking on all fours in a stiff-legged gait. On occasion they will stand on hind legs and walk short distances bipedally through the forest, grabbing branches as they walk.

The biggest threat to mountain gorillas (aside from civil war and shrinking habitat) come from meat poachers. People set wire snares for small game such as duikers (a small antelope) and bushbuck. Gorillas can become entangled in the snares, resulting in wounds and possible fatal infections. Youngsters, in particular, are at great risk. Starting with Dian Fossey’s first work here, trackers from Karisoke Research Center and park rangers regularly patrolled and removed snares. Now, with Hutu extremists hiding in the forest and staging raids, it is too dangerous. This puts the gorillas at great risk.

Female with a youngster perhaps only days old. This is part of the Suza Group in Volcanoes National Park, Rwanda. This family lives high on the slopes of Mt. Karisimbi, often roaming even higher – to 10,000 feet and above – in search of favorite food. This high elevation creates certain risks for gorillas. The cold and dampness increases likelihood of respiratory infections.

Life expectancy of mountain gorillas is considerably shorter than that of human beings. Silverbacks may achieve the age of forty to forty five years, females from thirty five to forty years. Family sizes range in number from just a few individuals to up to 30 or more. The dominant silverback is, of course, the leader. But there may be other subordinate silverbacks in large families. Gorillas do not defend a territory but do have home ranges that may be dozens of square miles in area. Sometimes there is conflict when one gorilla family encounters another in overlapping home ranges. At these times each silverback engages in what Dian Fossey called “hootseries,” a series of low pitched hoo-hoo-hoo sounds, building in volume and ending with the silverback giving an impressive chest-beating display or beating the ground violently. Sometimes the displaying silverback charges through the brush, tearing vegetation and tossing it about. Eventually one of the silverbacks triumphs in this intimidation game and the other group leaves. Occasionally, however, there are violent confrontations and with their great power and large canine teeth, serious injury can be inflicted – sometimes resulting in death.

Imbaraga was the silverback leader of the Suza group (named by Dian Fossey for the Suza River flowing near the home range of this family). This particular family was one of the largest, with 32 members in it in 1989. This is not a display of aggression – he was just yawning. But it does give an impressive view of those large canine teeth – you wouldn’t want to tangle with Imbaraga. Actually, he was pretty mellow and gentle, a favorite of eco-tour visitors to the park. On the day I made this photograph it was raining so hard that everyone – gorillas and people together – sat under some huge hagenia trees for shelter. We still got soaked. Sadly, Imbaraga, this splendid and gentle silverback, died about 7 months after this picture was made in September 1989. An autopsy revealed the cause of death to be pneumonia. It was reported by researchers that, as he lay dying, the members of his family came to Imbaraga and touched him or lay with him or otherwise said goodbye to their leader.

Imbaraga’s hand. Gorillas are extremely powerful animals. An adult silverback can weigh as much as 400 pounds and they are very agile. (They’d make great defensive linemen and some NFL football teams could use them!) Adults rarely climb trees, but youngsters and young adults will often climb bamboo to feed on the fresh green leaves on top. Among family members they are gentle giants. The rambunctiousness of pesky youngsters is patiently tolerated by adults. Rarely do you see any intra-family disputes.

Despite their great size and power, I have watched giant silverbacks carefully and gently groom the fur of youngsters only a few months old. They seem to be very well aware of their strength, but with members of their own family they are gentle giants.

Rugabo was the silverback leader of a family in Virunga National Park in Zaire. I made this shot on my first visit to the region, in 1988. To me it depicts a proud poppa – and I don’t think this is being anthropomorphic. These are very intelligent animals and are undoubtedly capable of a full range of emotions. Sadly, Rugabo became another indirect victim of the senseless civil war in the region. He was shot and killed, along with three other members of his family, in 1996. It was suspected that the killers were poachers trying to capture a young gorilla for the animal trade – in apparent hope of making a lot of money selling the youngster(s) to exotic animal dealers. If this were true, it’s even more tragic because any captured youngsters were doomed. Mountain gorillas do not survive in captivity. Few, if any, exist in any zoos around the world. So the only mountain gorillas the world will ever have must exist in their natural habitat – if they can. They must be preserved.

For more information on how you can help, contact the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund: www.gorillafund.org

by Boyd Norton

Leave a Reply