A sign outside the shrine read, “No pictures of the Buddha, please.” Okay, I thought, at least it will be warm inside.Fingers chilled by the freezing January mountain air just after an overcast, humid dawn, we walked up the gentle road to the quiet temple. We left our shoes at the door, next to rocks covered by moss and ferns. As our sock-clad feet slid easily across the polished wooden floor of the outer hall, we smelled an ancient combination of incense, mildew, and lacquer. The sun rose.

Looking up, we saw the three 16-foot high wooden Buddhas that could not be photographed. They were magnificent. Each figure was covered with gold leaf. Each one smiled.

Why were these particular Buddhas off-limits? Their temple housed a sacred mausoleum to Tokugawa Ieyasu and contained an inner hall open only to priests. These three Buddha figures were themselves sacred representatives of three local mountain peaks that had been worshiped for over two thousand years. A priest named Jikaku had built the Sanbutsu-doh. (“Doh” meant “hall,” and “Sanbutsu” meant “three Buddhas,” we learned.) Since the figures were sacred, we shivered respectfully, and tucked our cameras away. No pictures of the golden Buddhas.

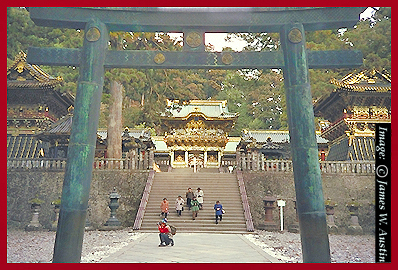

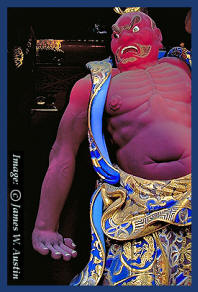

We had come to photograph the Toshogu Shrine, because five of its buildings were national treasures: Youmeimon gate, Karamon, the large bronze Torii gate, the Five Story Pagoda, and the Three Wise Monkeys. There was plenty to see elsewhere in the shrine and temple complex, such as the gate guardian (at right). Its fierce expression was meant to terrify. Guardians were placed outside temples to frighten away evil-doers. We gazed in awe at the two fierce guardians of the Youmeimon gate.

We had come to photograph the Toshogu Shrine, because five of its buildings were national treasures: Youmeimon gate, Karamon, the large bronze Torii gate, the Five Story Pagoda, and the Three Wise Monkeys. There was plenty to see elsewhere in the shrine and temple complex, such as the gate guardian (at right). Its fierce expression was meant to terrify. Guardians were placed outside temples to frighten away evil-doers. We gazed in awe at the two fierce guardians of the Youmeimon gate.

NIKKO (NĒ -KŌ)

Nikko rests right in the mountains, about 100 miles north of Tokyo, nestled serenely in a forest of centuries-old cedar trees. The Japanese have a saying about Nikko. Seeing Nikko’s treasures, it was easy to understand it. In English, the phrase is “Don’t say Magnificent until you see Nikko.” Because of its history, sacred mountains, and unmatched views through its torii gates, Nikko became a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2000.

From Tokyo, we arrived on the Tobu-Nikko train line. We took just a few selected lenses, and left the tripod behind because of the steep steps up the mountainside temple complex. Nikko’s humidity was hard on electronics; we carried all equipment in Ziploc bags with moisture absorbing pads. Cameras were allowed most places, with signs posted where they were prohibited. We went in winter, when the mists settle on Mt. Nikko, but fall and spring are considered the best times for photography.

While we explored, a park attendant offered hot buncha tea to ward off the chill. While we wanted rice wine, we arrived too early in the year for the sake festival. Each April 13th, Nikko throws a 4-day festival called Yayoi Matsuri, the park guide said, when the town residents have a parade of decorated floats, and sake is ladled out of the barrels and put in square wooden cups for all. Being practical, the sake brewers held two festivals a year; one was to pray for a good crop, and the second rewarded an abundant spring rice crop. These colorful sake barrels (left) were wrapped in plastic and stacked for aging are near the Roumon gate of Nikko’s Futarasan Shrine. We were astonished to see, in addition to sake, stacked barrels of aging whiskey in the Futarasan shrine.

PROCESSION of A THOUSAND WARRIORS

Sennin Musha Gyoretsu

Hands now warmed by the hot tea cups, we climbed up to a series of surprisingly ancient temples. In our modern times, it is tough to imagine how Japan’s great warriors lived. Nikko’s mountains are often cold and wet, and the frozen roads of the 17th century had to have been dangerous. Trade prospered, however, and the ruling Tokugawa family (whose crest is at left) dominated Japan’s economy. In modern times, the Toshogu shrine hosts the affluent “procession of a thousand samurai” every October 17th. This festival features horseback-mounted samurai wearing bright red garb riding at the head of a procession of armor-clad marchers, in which Tokugawa Ieyasu’s remains are carried in a sacred palaquin.

Hands now warmed by the hot tea cups, we climbed up to a series of surprisingly ancient temples. In our modern times, it is tough to imagine how Japan’s great warriors lived. Nikko’s mountains are often cold and wet, and the frozen roads of the 17th century had to have been dangerous. Trade prospered, however, and the ruling Tokugawa family (whose crest is at left) dominated Japan’s economy. In modern times, the Toshogu shrine hosts the affluent “procession of a thousand samurai” every October 17th. This festival features horseback-mounted samurai wearing bright red garb riding at the head of a procession of armor-clad marchers, in which Tokugawa Ieyasu’s remains are carried in a sacred palaquin.

SUPER SAMURAI

We saw Ieyasu’s armor and swords as well as everyday household objects in the Nikko temple collections. They were marked with the Japanese kanji character for samurai (right). A great warrior and leader, Tokugawa Ieyasu gathered builders and craftsmen from all over Japan to build his mausoleum at Toshogu. They also built the Youmeimon gate (shown at left).

We saw Ieyasu’s armor and swords as well as everyday household objects in the Nikko temple collections. They were marked with the Japanese kanji character for samurai (right). A great warrior and leader, Tokugawa Ieyasu gathered builders and craftsmen from all over Japan to build his mausoleum at Toshogu. They also built the Youmeimon gate (shown at left).

Toshogu shrine, as mentioned, was a memorial to this famous man. The last of three warlords who unified Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu was the very same character that novelist James Clavell wrote about in his book, Shogun. Although Ieyasu lived from 1542 to 1616, at Toshogu Temple, he seemed to still be alive. His image was everywhere. So, too, were carvings of animals, like the three wise monkeys.

SEE NO EVIL, HEAR NO EVIL, SPEAK NO EVIL

To truly understand the expression, “See no evil; hear no evil; speak no evil,” you have to go to Nikko and learn some facts about samurai life. Samurai were total warriors. They were ferocious, especially when mounted on horseback. In feudal Japan, horses were rare. Caring for horses was a sacred duty. The horse stable at Tokugawa Ieyasu’s mausoleum (below right) is itself a national treasure. It held the panels of the Three Wise Monkeys, painted carvings over the stable doors that portray the saying, “See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil.” A Buddhist monk from China introduced the phrase to Japan, perhaps via India and China, in the 8th century. Tied to Vadjra, an Indian blue-faced god with three eyes and many hands, the three monkeys’ poses demonstrated the god’s motto, “If we do not see, hear or talk evil, then we ourselves shall be spared all evil.” In India, this phrase had nothing to do with monkeys. In Japan, however, the saying came from a play on words. The Japanese word for “monkey,” “saru” sounded like the word ” zaru” that meant the negative form of any verb– i.e. “don’t.” The Japanese saying “mizaru, kikazaru, iwazaru” meant “don’t see; don’t hear; don’t speak.”

A BRIDGE OF SNAKES

Thus admonished, we continued upwards along the mountain road to Rinnoji Temple, where stood a stunning sculpture of Shoto Shonin, Nikko’s founder. His statue rested on black rock that shone when it was wet. Next to his figure, a small plaque described “Statue of Buddhist Priest Shoto, who civilized the mountainous area of Nikko.” To photograph the statue, I emphasized the foreground, where ice had formed around a cast bronze dragon whose breath was a frozen water spout falling into the well. An old legend about Priest Shoto, we learned, was that enormous snakes appeared and transformed themselves into a bridge at the moment when Shonin wanted to forge Nikko’s Daiya river.

LOOK ALL DAY AND NOT TIRE

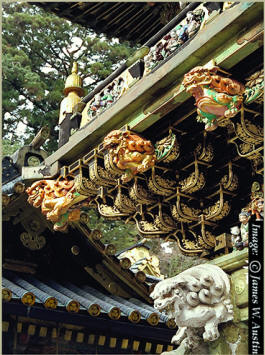

Dragons and monkeys and snakes–why was there a tsunami of weird animals at Nikko? In feudal Japan, people’s imagination invented many evils. Then, as now, the temples’ carved animals were considered good luck charms to ward off evil spirits. The Shinto shrine figures were there for protection, just like the gate guardians. One temple gate, called the Yomeimon for a gate in Kyoto, had 508 figures on it. Its Japanese name “higurashi-no-mon” meant that you can look at the gate until sundown and not tire.

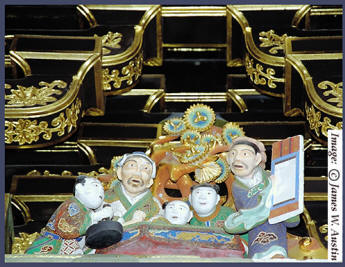

One reason you would look all day, our guide pointed out, was that many of the Yomeimon’s figures were parts of plays and story-telling theatrical scenes. (The play entitled “Calligraphy” is pictured below left.)

A bronze Buddha sat atop a grave site near a small shrine in central Nikko (below right). The cemetery stones were covered with green moss. We learned that this was one of Nikko’s oldest burial grounds.

STONE SPIRITS AND STAR WARS

Why can we find so much reverent artwork at Nikko? As well as Buddhist temples and mausoleums, there were many Shinto shrines built there. Art was a central part of Shinto. The term “Shinto” comes from two words: “Shin” means gods. The second part “tō” means “way” or “art.” Think of Shinto as “way of life” or “way of the Gods.” Shinto embodied a Japanese native belief system that cherished one’s ancestors and the spirits of nature called “kami.” Kami existed in both divine and earthly forces, including plants, animals, mountains, and stones. To Shinto believers, the world was good and people were good. While there was harmony in life, it was always threatened by evil spirits, who must be kept at bay. Does this theme sound familiar? George Lucas based his Star Wars themes on samurai and the culture of Japan. Lucas heard the Japanese word “jidai” meaning “age” or “time period,” and he came up with “Jedi” for his Star Wars knights.

PERSISTENT PAGODA

The Force was with us as we left our hotel room and braved the humid cold for another day of climbing Nikko’s mountains. Bolstered by a can of piping hot sake from a Pocari Sweat soft-drink vending machine, we pushed on to photograph the pagoda. Nikko’s five-story pagoda dates to 1650. After fires and earthquakes destroyed several previous versions, the present structure was improved, and it has survived. The 100-foot pagoda was constructed without individual floors, just a single open column in its center. A steel chain was hung from the height of the fourth floor to stabilize the building when earthquakes occurred. Photographing the pagoda was a challenge because of the sharp color contrast in the scene–a dark green forest surrounded the pagoda’s vivid red exterior.

BLESSINGS FOR CHILDREN & TRAVELERS

Leaving the cedar tree forest of the pagoda behind, we came across a stone park. One hundred carved stone figures rested in a long row in the valley near the Daiya river. These one hundred Bake Jizo (bah-kay-jee-zoh) were protectors for travelers and children as they journeyed to Nikko’s holy places.

Digging through the frozen soil to repair a statue, maintenance workers toiled, vigilant to protect their artistic heritage, while we looked on.

A STRIKING BELL

The Shōryōbell tower pictured here rang in New Year’s Eve just a few weeks before our arrival. Unlike bells of the western hemisphere, we learned that some Japanese bronze bells were rung from the outside; two horizontally suspended logs were used to ring the Shōryō bell. The bronze was cast so that two different tones emerged depending on which side of the bell was struck. The bell tower was carefully built with twelve pillars to hold the eight-ton bronze bell. Real and imaginary animals with mysterious powers adorned the bell tower: we saw cranes, flying dragons and even giraffes. We continued climbing up the steps to Nikko’s highest temple, as morning sun broke through the mist to illuminate it.

LIGHT FROM THE EAST

The Haiku poet Matsuo Bashō went to Nikko in 1689 and wrote this Haiku:

O holy, hallowed shrine!

How green all the fresh young leaves,

In thy bright sun shine!

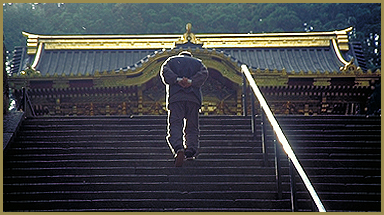

Bashō’s bright sun shine glowed on the last temple we saw, at left. A monk walked up the steps of a temple whose name meant “light from the east.” This rising light from the east symbolized the dawn of a newborn nation in the land of the rising sun. At it turned out, there was really no need to photograph the Buddhas, as sacred scenes were everywhere at Nikko. Taken as a whole with its Buddhist temples, hallowed shrines, racing river and misty mountains, it was clear that Nikko was a treasure. Its bright sunlight from the east seemed eternal. It shone through cedar trees on to old stone steps, slightly worn from the tread of countless reverent feet.

by James W Austin

Leave a Reply