In September of 1996, Mario Corvetto accompanied his wife Jeanine on a trip that would redefine the human spirit. They went to live in Bosnia for a year. Jeanine was assigned as a consultant for the U.S. Department of Treasury Office of Technical Assistance to advise the Bosnia-Herzegovina government on rebuilding infrastructure. Mario decided to donate his skills as a photographer in the hopes that his images might help the relief organizations to increase world awareness and raise funds for the rehabilitation of a country, its cultures, and its people. What follows is the first in a series of three articles dedicated to the silence after the bombs have stopped–and, in that silence, a heartbeat that signals the survival of the spirit. This segment focuses on the children of war. (Portions of the text were taken from an oral interview.) – Susan Harris

THE SPIRIT OF HUMAN STRUGGLE: BOSNIA

by Mario Corvetto

When my wife was offered a job to go to Bosnia, we felt–we have such a fortunate life in the United States–this would be an opportunity to give something back. For my part, it was an opportunity for me to utilize my photography as a tool to help the community. In an area like Bosnia where all the material aspects of the culture were totally destroyed, I expected the human spirit to be destroyed, as well. But what I found was the human spirit was very much alive. We met people who had been shot at, their families torn apart, their relatives raped, their homes demolished by hate. And these people were trying to love their enemies. Jeanine mentioned that it’s not easy to give love to people who don’t love you back, but that is the answer to the problems. And we found that there.

I want my photographs to show that bullets will not kill the spirit. You might damage it. You might transform it for a while, but always the spirit will reinvent itself in a way and come forward. This is what we experienced. We found a spirit of reconciliation–especially in the women. The women were the first ones to cross the forbidden lines to talk to the other women, because they were neighbors all the time. And they are the ones who may eventually get the communities back together. It’s going to be a formidable problem. During a visit to a farming community in Bosnia, I met a Muslim man who had lost his arm from a Serbian shell which hit his home. When I asked him about the possibility of his Serbian neighbors returning back to their homes, he replied, “One man–not a nation–took my arm. If I do not allow my Serbian neighbors to return home, I will be not only physically incomplete, but also spiritually (incomplete).”

I was in Bosnia for a year. As time passes and you hook up with the people, you become part of their family, not just a friend or acquaintance. Then you realize–and by that time it’s too late–that sooner or later you must leave, because Bosnia is not your home. But you feel that you’re abandoning a family, your children. You realize that your leaving will be even more dramatic for them than for you, because you have become one of the pieces they’re missing in their lives. We were the only persons to whom they could tell their stories, because everyone (else) had gone through the same nightmare. Trying not to feel the guilt of abandonment is our burden right now. On the other hand, we came out with a gift. They gave us a lot more sense to our lives than we could ever give them. The dilemma of sharing my images is how do you show these images to the world without hurting again these people who are already going through a process of healing? The last thing you want to do is to betray the gift that you have received.

It’s not trivial. It’s not easy. And it’s not easy to talk about. I feel that it’s important for me to tell you about the everyday heroes who will never have their fifteen minutes of fame. Only the dead ones made the news. They sold commercials! The more they bled, the tighter the image.

This experience is not one about which someone can say, “Hey, Mario, how was your trip to Bosnia?” I can only write from my heart and from my experiences and observations. A difficult task considering that I write with my eyes, not with a pen.

How much time do you have?

What do you really want to hear?

That is the difficult part.

“ALBRIGHT’S GIRL”

I photographed this young girl for the American Refugee Committee during the inauguration of a USAID funded playground at a preschool in Sarajevo. I was fascinated by the girl’s personality. She was so dynamic, open, and perceptive–even though she had lost her family during the siege of Sarajevo and was now living with her grandmother, her only living relative.

Ironically, I returned to the playground some time later with the Secretary of State Madeline Albright during her visit to Sarajevo. The little girl presented her with a flower arrangement. Neither Madeline Albright nor the crowd of dignitaries was prepared for what happened next. The little girl hugged the Secretary of State and, through a translator, told her please not to leave, not to abandon her or her friends. That really shook up Ms. Albright. During the entire visit at the playground, the little girl refused to release her hold on the Secretary. Everywhere Ms. Albright walked, there was the little girl clinging to her dress. Later, I photographed her and Madeline Albright exchanging kisses. I named the image “Albright’s Girl” as a tribute not only to the girl’s spirit but also to a diplomat who recognized the need to meet with the Bosnian community during her stay in the country, choosing to spend time with them rather than with high level officials.

“CHILD’S CROSSING”

Coming from a place like Colorado, I’m accustomed to seeing signs riddled with bullet holes, and–to be honest–I’ve never paid much attention to them. But in Bosnia, this crossing sign really put into perspective the whole “Sniper Alley Experience” that the people in Sarajevo had to endure. I was working in an area were sniper activity had been very active during the siege. The surreal energy I felt standing on that street made the sign come alive. I watched children running for their lives. I could hear the screams, see the image of the young boy found dead on the pavement who–just minutes before–was collecting water to take home. It was as if the pail of water he was carrying had hit the flame of a lit candle and now there was only darkness. I’ve never been affected by a sign the way this sign affected me, and I have not experienced that energy again after my return home.

“CHILD’S PLAY”

I have a series of photographs of children playing in the Muslim cemetery located across the street from our house. To me it was amazing that the children chose the cemetery as a playground for war games. They seemed to have an incredible appetite for playing with guns–something one could probably see all over the world, but here, after the war, I didn’t expect their parents to encourage or permit violent play. On Friday nights, from our bedroom we could hear men shooting their automatic weapons into the air. Guns were even present at funerals. After having to endure such a cruel siege, perhaps the guns gave the people a greater sense of security.

In an effort to create mine awareness among children, the UN began a poster campaign featuring Superman saving children from the dangers of mine fields. On one of my visits to the schools, I asked the children what they thought of Superman. They told me one of the reasons they didn’t like Superman was Superman was a wimp. They wanted somebody mean and strong, someone who could really go out there and “kick ass,” so they weren’t interested in nice people. They wanted someone who could protect them. They wanted their parents and their older brothers to have bigger and more powerful guns. After three years of war, their heroes are all soldiers. “NATO soldiers have no capes, but (they) carry big guns and they protect us.”

“CLUBHOUSE”

“CLUBHOUSE”

The clubhouses I visited are operated by Catholic Relief Services (CRS) and opened their doors in 1996. CRS recognized that while many humanitarian organizations were addressing the needs of young children, orphans, and the elderly, the teenage youth in Sarajevo were not receiving sufficient support in coping with the traumatic consequences of the war. The CRS Youth Clubs provided a variety of programs in education, self-esteem and community service.

These clubhouses and playgrounds (in which the American Refugee Committee is involved) also give kids a safe place to play, because there are many mine fields. Typically, their houses are totally destroyed. There’s a lot of stress in the family. This is an area where kids can play with other children. Maybe they’ve been separated from one another for a long time. Maybe some of the kids in the neighborhood are refugees and don’t know anyone. The clubhouse is a place to learn languages, get involved with computer classes, take art classes, acting, dancing, music, art. It’s a way for the children to deal with their trauma. The atmosphere is wonderful there.

One of the things I heard from the children was that returning to their damaged houses was like someone turning off the lights. They felt that going to the houses was going back into a situation that was devastating. The club was clean, painted, and it had lights. It always had a really positive attitude. There were support people there to make sure the children could go through the process of rehabilitating themselves. A clubhouse is where children can start expressing themselves again and feel comfortable.

I was overwhelmed by the way these children received me with open arms. Even after all the suffering, they were still able to give affection without expecting anything in return. If I learned anything in Bosnia, it’s that the children are the most resilient humans, and we adults have much to learn from them. I found these two young girls hugging on the steps outside the club. After three years of hiding in basements apart from one another, physical contact is one of the ways in which the young people support and nourish each other.

“CRIME PAYS” –drawing

This is a drawing by one of the school children participating in a program offered by World Vision International. The program, called Creative Activities for Trauma Healing, was designed to facilitate healing from war trauma. Drawings such as this one can be done in the clubs, or the psychologist and the group of people who are working with the children can go to the schools. Once or twice a week, this team of experts–local experts who’re also dealing with their own trauma–put their pain aside to go help the children. When the children are doing the drawings, the parents are there in their classes, because what the experts are realizing is the children have become more aggressive at home because they’ve experienced a lot of trauma. However, the children aren’t the only ones who need help. Their parents have been traumatized, as well. So, this program is attacking the problem from all different directions. The ironic part of it is these teams are the folks who have to struggle to find funding. The type of psychological support a community needs that will make sense, that helps get people back to a sense of normalcy, that is the most difficult money to receive.

The drawing is an interpretation of how war is profitable for war criminals and organized crime. It depicts how an unscrupulous group of individuals have benefited from the war through the selling of food, medicine, and weapons in the black market. Many of these criminals have high level political positions, send their children to elite private schools in western Europe, drive luxury cars, and eat in the most expensive restaurants. Another idea of this drawing is that the people who are being given the money to reconstruct the country are the same people who started the war. So, this is a fourteen-year-old kid who has come to the realization that the war has rewarded the bad people. That’s why the drawing is called “Crime Pays.”

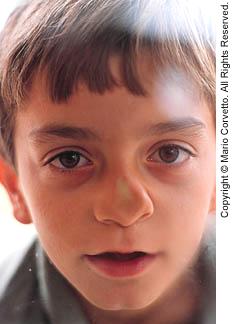

“CRYING GAME”

On the surface and at first glance, the children in Bosnia appear to be very happy kids—like kids anywhere. With time, they began trusting me. Then I began seeing the other side, the dark side caused by the trauma. Many times when they were unaware of my presence, I saw the children going back inside themselves, to a place where an innocent child no longer lives.

When I photograph children, it’s imperative for me to look into their eyes. On the surface, the first reaction of children anywhere in the world is to give. So they’ll always give you that smile. After the smiles are put aside, it’s the shine of their eyes that tells me the truth. Like a book, I’m able to read if they’re healthy and happy or if life for them is a nightmare.

This image represents that window on reality–her eyes.

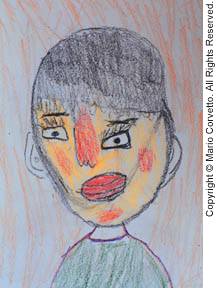

“CRYING GIRL” – drawing

“CRYING GIRL” – drawing

The self-portraiture drawings by children answer the question, “How do you feel about yourself?” I was disturbed to see how children painted themselves very ugly or crying. At that moment, you allow the children to express who they believe themselves to be inside, because the smiles are hiding everything outside. The drawings are very honest. The children don’t feel good about themselves. They don’t like who they are, because of what they see around them and what they see their future as adults may be. They realize their family has been devastated. They realize their innocence is gone. I talked to a seventeen-year-old young woman who, at the time the war started, was fourteen. She went from being someone who was totally afraid of seeing bugs, to being someone who could see brains splattered on a wall and be unaffected by it. So that individual doesn’t like herself. These are people who have taken the destruction inside. They’re not blaming anyone. They’re blaming themselves. There’s something inside that says, ” Maybe I’m a part of it. Maybe it’s my fault.”

“RED-NOSED” DRAWING

“RED-NOSED” DRAWING

Just by looking at this picture, you can see that this child really feels a lot of stress, a lot of tension. Note the wide eye, the red nose, and the twisted mouth. Plus, he considers himself to be a person who is very ugly inside. Images such as this one demonstrate the terrible emotions disturbing children from within.

“FAT BOY IN WINDOW”

I assign this child a label because no matter where you are in the world, it seems that kids who are overweight are picked on. The other kids make fun of them. These kids are often shy. This boy was very curious about what I was doing at the club, after seeing me there some four or five times. He would follow me, but he repeatedly created a barrier between us. At the moment I photographed him through the window, he had his face pressed against the glass. He was watching me as I was photographing a group of young women making masks. In a sense, I felt a connection with this child and our exchange of smiles from a distance was a form of communication and friendship.

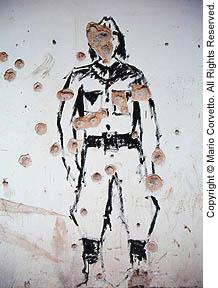

“HEROES FOR IDIOTS” – drawing

This drawing was on a wall in a city called Mostar, a city divided between Croats and Muslims. Probably the worst hand-to-hand combat that occurred during the entire war happened in Mostar. For a time, the Croats and Muslims were fighting together against the Serbs, but for very complicated reasons the allies turned on one another.

The title “Heroes for Idiots” just came to me on the spur of the moment. I saw children playing bootlegged versions of violent computer games such as Mortal Combat. The pumped-up steroid action figures were the children’s heroes. I found this disturbing, particularly since there was so little separation between the game and real life. It was not a computer game anymore.

“MASKS”

Creating masks as an art project was an idea put into action by a team of psycho-social workers teaching art and crafts at the clubs. To me, the masks provided a way for the kids to become someone else, maybe to escape. Being able to hide behind the masks gave them the freedom and security to exhibit different behavior or communicate the feelings they were holding inside. I think people, in general, wear masks in different stages of their lives. The blank mask in the image had a powerful effect on me. In a way, the mask revealed to me the uncertain future that awaits the young people in Bosnia. For them, it’s very difficult to see ahead; their future is blank. Only time will tell how the war children will react to the therapy and support they are receiving at the present time.

“MINE VICTIMS”

The children in this image have all suffered physical losses due to land mines. The goal of my photography was to convey a sense that although their bodies might be incomplete, these children still have their minds and spirit. If they’re treated properly and given the right support, they’ll become an asset to their society. In a sense, these children taught me that maybe I am incomplete, since I live in a society so preoccupied with the physical and material aspects of our lives that we don’t realize we are spiritually handicapped.

Walking into the computer room where the children were taking a class was overwhelming. There I was with my camera, the children looking directly at me with such self-confidence, their eyes asking the question, “Why are you here and what do you want from us?” The staff told me the children would be the ones making the decision to allow me to work with them.

The children are very much involved with computers and the club’s activities. The staff at the club will make no special concessions for them. All the children at the club are treated equally. In the clubs, the effort to provide the children with a chance for a positive future is tremendous. Now it’s up to the Bosnians to be prepared to deal with the overwhelming number of physically challenged people who have become part of their society–from the building of access ramps and adequate public transportation, to the establishment of schools and the creation of jobs that integrate the physically challenged into the work force. Only time will tell how the society will cope.

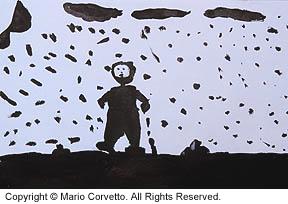

“RAIN SHOWERS”–drawing

This drawing of rain showers puts into perspective what the children must have felt for three years during the siege of Sarajevo, when they watched people being killed by shelling or snipers. The barrage of bullets continued day and night. One study found that the children who drew really graphic pictures were usually drawing not something that happened to their own family, but something they had witnessed happening to someone else. They couldn’t stand to report tragedies which had befallen their own families with so little reservation.

“PARENTS AND PARACHUTES” – drawing

Historians are calculating that six million rounds of artillery fell into Sarajevo alone in three years. When I looked at this drawing of parents missing legs and arms, a tombstone, a shell that’s exploded, and enemy soldiers coming down in parachutes, it made me think. I wrote a poem about how you never expect the mortal game to come alive and your parents to become your heroes.

HEROES

Never thought of them as heroes,

Your playgrounds turned to battlefields.

This was real, no “mortal combat” computer game.

To kill you, your parents, was the final aim.

Real heroes of flesh and bones.

She nursed, held you. He lifted you high,

Gave you your name when you were born.

Now your family is forever torn.

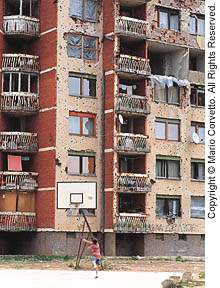

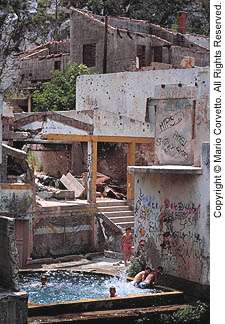

“PICKUP GAME”

I went into the neighborhoods to get a feeling of what the children go home to when they leave the nice, clean, reconstructed environment of the clubs. I found this boy playing by himself. Since the background is the essence of solitude and devastation, I began to wonder whether this boy was really playing basketball or merely trying to escape his reality.

“PLAYGROUND”

After spending time with the children in the clubs, I was upset by seeing them in the playgrounds. When the children are in the neighborhoods, they react totally differently to their environment. They’re confused. Everything they had at one time–their concept of what the family is, what the future could be, even who their friends are, is totally destroyed. As they look around the area where they live, they realize life is not going well. Although billions of dollars have been pumped into the country of four million people, the recovery of the individual families is agonizingly slow. What a difficult condition to live with–no electricity, no running water, and no jobs. The children are going to school, but the inevitable question is, “What am I going to school for?” They have many questions, questions with no answers. In the image of “Playground,” a child sits on a swing, which is supposed to represent fun. But all he’s doing is moving like a clock–going back and forth with his head down. His body posture says he wants only to escape the moment. The situation doesn’t say “fun.”

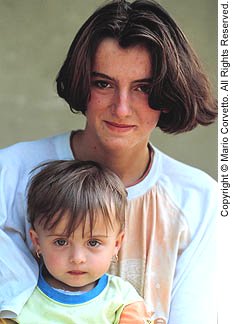

“PLUM TREE BABY”

This family calls their infants “plum tree babies,” because they’re members of a family that used to have a farm up in the hills where they tended over three hundred plum trees. They had a very good business. As a farming family goes, they were self-sufficient. When I met them, they were refugees. From the place where they were staying, they could see their land. But the whole place was mined, so it was not safe for them to go back–and probably wouldn’t be safe for years. The wrenching part for them was taking over someone else’s home, being refugees, because they had always been hard-working and self-sufficient. When they found out we were coming, they prepared a really incredible meal for us, hoping we could help them to reconstruct their home in a different area. The spirit that came out was just tremendous.

This family calls their infants “plum tree babies,” because they’re members of a family that used to have a farm up in the hills where they tended over three hundred plum trees. They had a very good business. As a farming family goes, they were self-sufficient. When I met them, they were refugees. From the place where they were staying, they could see their land. But the whole place was mined, so it was not safe for them to go back–and probably wouldn’t be safe for years. The wrenching part for them was taking over someone else’s home, being refugees, because they had always been hard-working and self-sufficient. When they found out we were coming, they prepared a really incredible meal for us, hoping we could help them to reconstruct their home in a different area. The spirit that came out was just tremendous.

They had been forced to flee, because they happened to be from a different ethnic group. I can probably show this picture to a million people and the last reaction I’d get is that this woman is a Muslim. (The young woman is about seventeen, and the little girl–her sister–is about two years old.) You come into a culture with an impression of what a Muslim is, but the fact is, Muslims are just like anyone else. It’s important to separate the war ciminals from the population of a nation. Every society has their struggles and their lives and the good and the bad. These people made me feel welcome. They were refugees, but they opened their house. It was amazing to me.

“SARAJEVO GIRL”

No other image I’ve done of children in Bosnia will represent what I felt there as poignantly as this child. She could be the poster child for what’s happened to that culture. This child in that specific moment had a look of anger, a look of sadness. I could see the story of Sarajevo and Bosnia just by looking at her. Her eyes told me the whole thing. She’s a Muslim child.

“SPINNING BOY ON PLAYGROUND”

One of the comments I heard from one of the facilitators at the clubs is there’s a very big difference between the children from the cities, and the children from the countryside who come as refugees into a place like Sarajevo. There’s a lot of tension in the neighborhoods, because you have people who consider themselves to be sophisticated, city people, and then you have the peasants. The two groups have totally different ways of living. The country children have a difficult time understanding how to play in an urban environment, so they act out. This image of the merry-go-round whirling around gave me empathy for how these rural children must feel going into an environment surrounded by buildings, their lives in two little rooms instead of being in the countryside. Many of the playgrounds are torn up and destroyed after only a month. There’s a lot of maintenance to be done because the children become very aggressive. Apart from the war trauma, they’re disturbed by being removed from a familiar environment. The question now is how to deal with this situation.

“WINDOW VIEW”

“Window View” demonstrates the shyness the children may exhibit, because many of them have been living in basements for so long. They’re curious and they watch to see what’s going on, but always from a safe distance, behind a pane–with their faces pressed against the glass. Ironically, although the glass allows people outside to see in, the children seem to feel its barrier loans them security. If I tried to photograph them without the glass between us, even though I kept my distance, the children would move away from me immediately.

“Window View” demonstrates the shyness the children may exhibit, because many of them have been living in basements for so long. They’re curious and they watch to see what’s going on, but always from a safe distance, behind a pane–with their faces pressed against the glass. Ironically, although the glass allows people outside to see in, the children seem to feel its barrier loans them security. If I tried to photograph them without the glass between us, even though I kept my distance, the children would move away from me immediately.

During the war, many buildings were exposed to artillery shells and sniper fire. So, the people took refuge in the only shelters they had–their basements. When they went out for water or supplies, they were ready targets for waiting snipers. The children often made the mistake of thinking they could sneak out and play soccer on an empty school yard or in an abandoned warehouse. But the Serbs, who were surrounding the city, would hear the activity and direct their shells to the sound. That was how many kids died. The children hadn’t developed a keen enough concept of danger to keep them safe.

So, the community survived in the basements. There, classes went on and the children were educated. Story-telling thrived, because without electricity, you don’t have television. Apart from all the terrible conditions of the war, the sense of community was enriched. In fact, now that the war is over, the people of Bosnia are realizing they have to function as individuals again, and they are struggling to make it. They miss the war for some of what it brought to them–the urgency of being one strong community in which the members are intimately dependent on each other. That sense of community is gradually disappearing. Life seems fragmented. The material aspects of life are gone–not only the old neighborhoods, but also the old networks of friends and families. Those who aren’t dead, injured, or traumatized to the point of no return may have relocated to another country. Now there are people dying of depression. For them, the reality of reconstruction may be the most difficult part of the war. I think everybody who knew would tell you that Bosnia–especially Sarajevo– was a magical place before the war, where everybody was tolerant of each other. The magic will never come back–that’s the fear people have of the future.

“ZOMBIE” DRAWING

To me, this zombie drawing represents how not only the children but also the adults are walking around in a state of shell-shock. They’re going through the motions of everyday life, because society demands that they survive. People are working. People are going to bars. People are smiling and laughing again, but in reality what’s inside is totally something else. I remember a friend who seemed to have weathered the war very well. He had one of the best jobs anyone could ask for under the circumstances. He was working for an American representative of the international community and was making money in precious American dollars. He spoke English and was working with computers. However, in reality, he said the thing he wanted most in life was to be able to afford a motorcycle, so he could drive so fast that everything he had in his memory would be ripped out of him by the wind. The people are going through the motions of living, but they are zombies inside. They need a lot of time to recover. They never expected this to happen to them.

So, the community survived in the basements. There, classes went on and the children were educated. Story-telling thrived, because without electricity, you don’t have television. Apart from all the terrible conditions of the war, the sense of community was enriched. In fact, now that the war is over, the people of Bosnia are realizing they have to function as individuals again, and they are struggling to make it. They miss the war for some of what it brought to them–the urgency of being one strong community in which the members are intimately dependent on each other. That sense of community is gradually disappearing. Life seems fragmented. The material aspects of life are gone–not only the old neighborhoods, but also the old networks of friends and families. Those who aren’t dead, injured, or traumatized to the point of no return may have relocated to another country. Now there are people dying of depression. For them, the reality of reconstruction may be the most difficult part of the war. I think everybody who knew would tell you that Bosnia–especially Sarajevo– was a magical place before the war, where everybody was tolerant of each other. The magic will never come back–that’s the fear people have of the future.

“MOSTAR POOL”

I was working in the city of Mostar, and I kept hearing a sound of someone playing in a pool. It’s some kind of miracle that this pool would hold water. Everything around was totally destroyed. Mostar pool expresses how we need to learn from children. It’s located in the Muslim side of Mostar, which is now, after the war, a city divided between the Catholic Croats and the Bosnian Muslims. In this pool all the kids come together to play–regardless of their ethnic background. I felt if the politicians would get together in this pool, they might get something done. Even after a war, children get along. To them prejudice is just ridiculous. These are the same kids who create the drawings and graffiti around the city, going against authority, what authority wants them to do, even what their families want them to do. They represent a hope for the future, hope that counters the rhetoric which holds that if you’re Christian, you’re different; if you’re Muslim, you’re different; and you must maintain that division.

by Mario Corvetto (as told to Susan Harris)

Leave a Reply