© Dennis Cordell. All rights reserved.

I consider myself to be a portrait photographer, as opposed to a travel photographer. However, I have been photographing in India for over 25 years and this country is for me what Yosemite was for Ansel Adams or the American West was for Richard Avedon. India is a photographer’s paradise. Whether you work in color or black-and-white, India has a photograph-in-waiting wherever you turn.

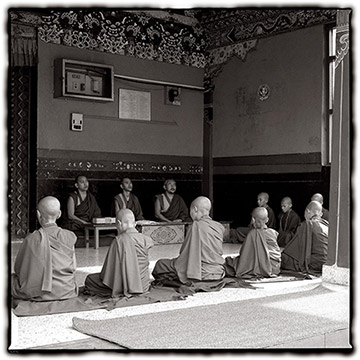

The majority of my photos were taken either in Bodhgaya in eastern India or at Tashi Lhunpo Monastery in south India.

Bodhgaya is the modern name for Buddha-gaya, the site of the Buddha’s enlightenment. The town of Bodhgaya is situated on the banks of the Nairanjana River, a southern tributary of the Ganges near the ancient Indian city of Rajagrha. It is at Bodhgaya that this seat of enlightenment, known as the bodhimanda, is located. Seated beneath the Bodhi-tree approximately 2,500 years ago, the Buddha Shakyamuni gained enlightenment. It is at Bodhgaya where both the Bodhi-tree, which is now grown from the sapling of the original tree, and the bodhimanda are enclosed within the gates of the Mahabodhi Temple. Today, thousands of Buddhists pilgrims from all over the world flock to the Mahabodhi Temple to recite prayers and mantras, and make offerings to the Buddhas.

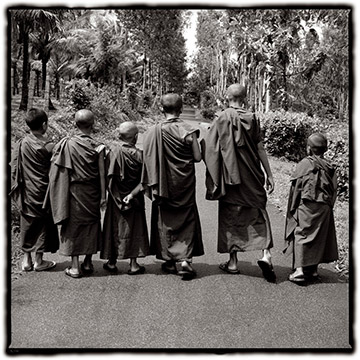

Tashi Lhunpo (bkra shis lhun po) Monastery was one of the principal monasteries of the U-Tsang Province of Tibet. The monastery, founded in 1447, is one of the six great monasteries of the dGe lugs pa tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and became the largest and most vibrant monastery in Tibet. It was, along with other monasteries, destroyed by the Chinese invasion of 1959. Tashi Lhunpo Monastery was reestablished in Bylakuppe, Karnataka State, South India in 1972, and despite a history of many obstacles, today there are over 350 monks in residence and the monastery is once again an important center for the preservation of Tibetan Buddhist culture.

© Dennis Cordell. All rights reserved.

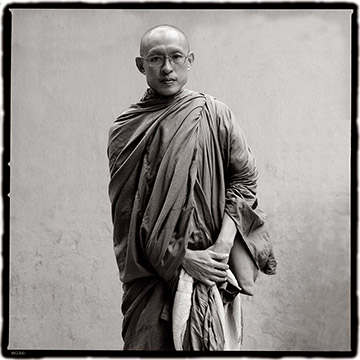

Like many photographers, I was trained as a painter. I bought a Nikon FM about 30 years ago to aid me in painting portraits. I would photograph my subject and then use a grid to transfer the image to canvas for painting. I soon realized that I liked shooting photographic portraits more than painting portraits and eventually moved from the 35mm format of my Nikon to the 120 format of the Hasselblad. These days I shoot film primarily with a Hasselblad 501CM using a 100mm lens.

I prefer the square format of the Hasselblad as opposed to the rectangular format of 35mm. A camera lens is round (like the Japaneseenso, the Zen circle, ofhitsuzendo, the “Art of the Brush”) and can perfectly contain the equilibrium of a square (creating the format of themandala), whereas a rectangle creates stress when part of the lens has its view “cropped” by one of the rectangle’s sides. A sense of order is maintained by a circle and square format. The perception of symmetry, or order, has, for me, an exemplar in the Sanskrit termrta–the natural cohesion that regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it. Its meaning is both “order” and “truth” and may be collectively referred to, in its ordinances, asdharma, and individually, in relation to those ordinances askarma. Rtais the opposite of chaos.

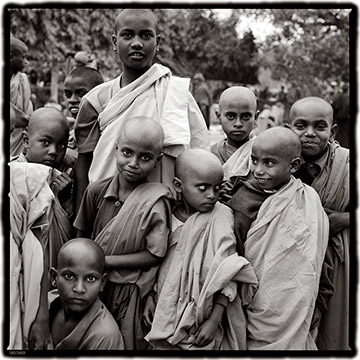

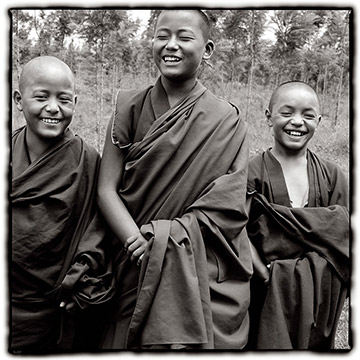

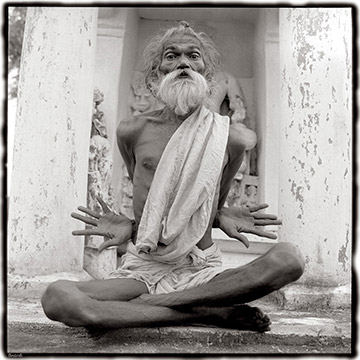

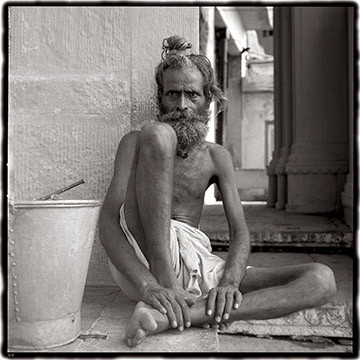

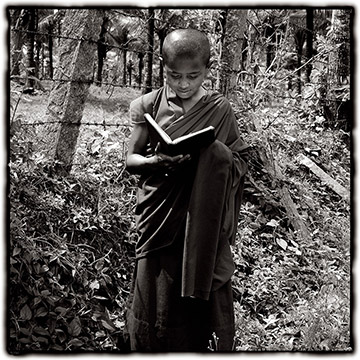

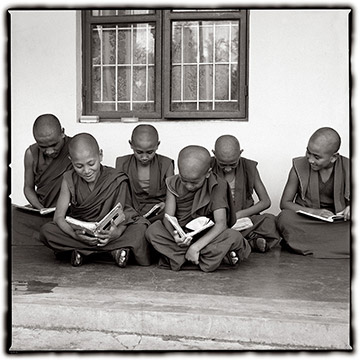

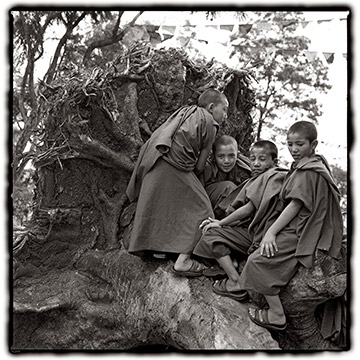

My favorite subject matter, in either painting or photography, has always been portraiture. I love the human face. Many of my earlier shots were of Sadhus, the holy men who frequent the temples and ashrams. Later I became intrigued with Buddhist monks with their wonderful shaved heads and flowing robes. They are happy to pose for a photo and they aren’t concerned with whether their portraits are cosmetically appealing. For them, a photo of themselves is simply a memento to gloss a particular occasion. Westerners often ask for “photoshop favors” such as bag, wrinkle, or chin removals. Buddhist monks know that wrinkles are just part of the impermanence of the phenomenon we call life. Future lives will bring more than enough facelifts!

© Dennis Cordell. All rights reserved.

© Dennis Cordell. All rights reserved.

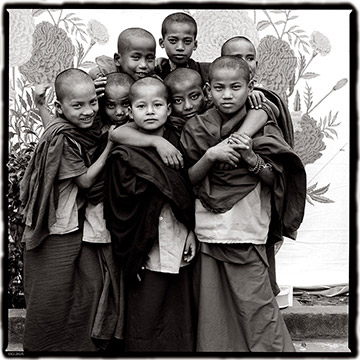

The younger monks used to seem mystified by my camera, especially when I would load film. At first I thought it was because they had never seen a camera, then I realized that the younger generation (even those who are not monks) simply had never seen film!

Monks, especially the young ones, are more eager to help as an assistant, and I often have three or four young monks helping me carry tripods and camera bags and work as “stylists” for all my portraits. Also they love to practice their English.

© Dennis Cordell. All rights reserved.

For me, composing the portrait through my viewfinder is homologous with the Indian notion ofdarshan.Literally,darshanimplies “to see” or “sight.” But, more specifically,darshanis concerned with an event in consciousness that creates an interaction between the seer and the seen. Thusdarshanheightens consciousness. Another term israsa, literally meaning “juice” or “essence.”Rasadenotes an essential mental state dominated by a primary experience of the viewer by that which is viewed. For merasais a vital component in photographic composition, similar to what Roland Barthes has called the photograph’snoeme. Photography is like meditation: the film roll is the string of prayer beads, while the sound of the shutter is the orison of the mantra of what is here and now. The shutter closes to create the silence of a history in which the narrative became the past tense.

I shoot film because it is easiest for me. I don’t like all the configurations and buttons necessary to operate a digital camera. A light meter involves enough computation. I don’t need an entire dashboard. Likewise, I shoot in black-and-white…again because it is easy, both in development and postproduction. I also like the abstraction that black-and-white creates on a paper’s surface. Similar to viewing the work of painters like Franz Kline or works by great calligraphers working in black ink, the viewer’s imagination is called into play when it encounters black-and-white photography.

This is how I “view” it: There is a wonderfulminimalismto black-and-white photography. The mind isn’t immediately told that what it “sees” is a “realistic” image or message. The mind first must decipher the tonality and contrast of the viewed subject in order to gain a meaning. The highlights and shadows of a black-and-white photograph are the warp and weft that create the “fabric” of the photographic tapestry. The greater the range of tonality between black and white, the greater is the image. A photo can never have too many shades of gray. Grays are the mid-tones that create the designs and textures woven into the photo.

© Dennis Cordell. All rights reserved.

I see myself as an artist who uses “lens-media”. I have always felt that using black-and-white film in my photos of India is neither optimistic nor pessimistic. A photograph is just an image on a piece of paper…it can be blown away in a gust of wind. It is minimal, even in color photos. It definesbrevity. It defines a moment…it is a visual Haiku (an unrhymed verse form of Japanese origin).

The photographer Diane Arbus stated, “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you the less you know”. And Robert Frank stated that within a photograph, “the visual impact should be such as will nullify explanation.” Put more succinctly, “a picture is worth a thousand words” even if those words are kept secret. It is photo minimalism that has the appearance of truth.

The nineteenth century British photographer William Henry Fox Talbot referred to the camera as the “pencil of nature.” My camera is more of a Pandora’s box. When the shutter opens, all the darkness in the box flies out into the world, but light enters and captures the “hope” of a good photograph.

by Dennis Cordell

Leave a Reply