(Editors note: Part one of this article appeared in July. All pictures seen below, as well as additional images, can be seen in a larger version by clicking on the link at the end of the article.)

After the return of my wife and I from Sarajevo, my friends wanted to know what we went through during our yearlong stay in Bosnia. They wanted to hear the stories the Bosnian people shared with us regarding their lives before and during the war. They wanted to ask what hopes and apprehensions fill the minds of the people as they look toward the future.

After the return of my wife and I from Sarajevo, my friends wanted to know what we went through during our yearlong stay in Bosnia. They wanted to hear the stories the Bosnian people shared with us regarding their lives before and during the war. They wanted to ask what hopes and apprehensions fill the minds of the people as they look toward the future.

Words have never helped me express my feelings. When I become emotionally charged, I take issues to a personal level, an action which produces a different effect from what I envisioned in my mind. I talk too fast, and my mouth works faster then my brain. My cameras, on the other hand, give me a chance to process my thoughts before I register them on film. My images are a form of language for my expression of love, happiness, concern, injustice…. My photos produce the same results I have sought with words. I feel safe communicating with my photography, because I am committed to never allowing my Leica or my images to be a weapon. I believe they are a constructive tool to bring light to even the most unjust of conditions. In Bosnia, I learned the importance of communicating with words and the need for constructive dialogue. My Bosnian friends showed me the ugly side of aggression.

I now feel that it is important for me not only to show you the faces of the Muslim, Croat and Serb people I met in Bosnia, but also to tell you with words about the everyday heroes who will never have their fifteen minutes of fame. Only the dead, the burning buildings with the smoke-blackened sky for a background, the fear in people’s faces as they ran “sniper alley” made the news. Those images sold prime time commercials! The more the people bled, the higher the flames and smoke, the more tears, the tighter the frame.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina, where all the material aspects of the country were totally destroyed, I expected the human spirit to be scarred beyond recognition. But, to my surprise, I found a generous, giving people who put aside their sorrows and hardship to make my wife and I feel welcome. I realized immediately after our arrival that inside the bomb-torn buildings, the human spirit was very much alive.

I believe that it is important to understand that in Bosnia, during as well as after the war, people were forced to divide along ethnic and religious lines. In places like Sarajevo, Muslim, Croat and Serbian people who refused to accept the lie, heroically defended the principles of human civility with their lives. It is important, also, to separate the war criminals from the population of a nation. In Germany, we do not call all Germans Nazis, and it would be tragic to think of all Serbs as criminals.

With Homage to the Cemetery

My wife and I met citizens who had been shot at, their families torn apart, their relatives raped, and their homes demolished by a group of people gone insane. We also came across those who believed the lie told by charismatic leaders who used religious and ethnic differences to gain power, territory, and money–a lie, unfortunately, that we in the West readily embraced for our own geo-political conveniences. There were many people talking about reconciliation–young people, especially–dreaming of returning to the magic they once had, longing for places like Sarajevo to be once again a city of tolerance, unity and love.

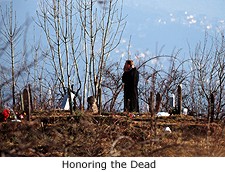

We found a house on the hillside overlooking the city of Sarajevo. What made this home special was the location: next to us, there were two Muslim cemeteries. What a beautiful tradition the Muslim people have in Bosnia–to bury their loved ones near their home. People stop and greet their loved ones every morning as they walk to work and wish them good night on their way home. The ceremony the Muslim people perform for the dead as they walk by is a very simple but powerful gesture. They acknowledge the dead by extending their arms in front of them with open palms towards the sky, and then placing their hands to their face. After a brief moment of prayer, they continue walking down the hill toward town for another day of work.

From Death, Life

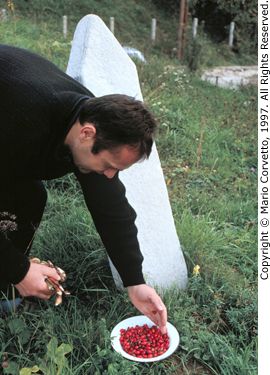

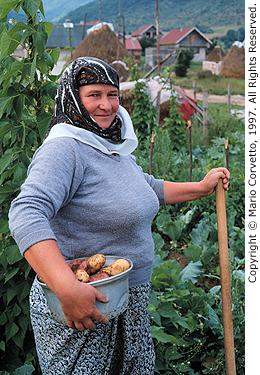

Because of the war, every little space of land available in these small cemeteries has been taken to bury family members. Ironically, the graveyards have assumed a secondary, yet very important role. The fertile land helped keep people alive during the war. The people from the neighborhood turned the area into vegetable gardens during the three year Serbian siege. Now, with unemployment running between seventy and ninety percent, the people in the neighborhood continue to cultivate potatoes, cabbage, spinach, carrots and even wild mushrooms. As a welcoming gesture, our landlady came to our home one day with a harvest of potatoes and carrots from the cemetery. Another neighbor came with a plate full of cooked wild mushrooms. It is ironic for us “Catholics” to have Muslims help us realize the true meaning of Communion.

Because of the war, every little space of land available in these small cemeteries has been taken to bury family members. Ironically, the graveyards have assumed a secondary, yet very important role. The fertile land helped keep people alive during the war. The people from the neighborhood turned the area into vegetable gardens during the three year Serbian siege. Now, with unemployment running between seventy and ninety percent, the people in the neighborhood continue to cultivate potatoes, cabbage, spinach, carrots and even wild mushrooms. As a welcoming gesture, our landlady came to our home one day with a harvest of potatoes and carrots from the cemetery. Another neighbor came with a plate full of cooked wild mushrooms. It is ironic for us “Catholics” to have Muslims help us realize the true meaning of Communion.

During a visit to a farming community in Bosnia, I met Radgi, a man who had lost his arm from a Serbian shell that hit his home. When I asked him about the possibility of his Serbian neighbors returning to their homes, he replied, “One man, not a nation, took my arm. If I do not allow my Serbian neighbors to return home, I will be not only physically incomplete but also spiritually (incomplete).” These words took me by surprise, but I soon learned that to have peace–not only in Bosnia, but throughout the world–the people must forgive and show love toward the ones who inflicted so much pain. This difficult task is the key to the rebuilding of a civil society, and it was our lesson in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

As time passed, and we met the people in our community, we became part of their family–not just a friend or acquaintance. It was as if they had waited for our arrival, as they would await a lost member of the family. It seemed to them that we had been gone for a very long time. We were the only persons to whom they could tell their stories, because everyone around them had gone through the same nightmare. They felt as though they had waited for five years to catch up on things.We had to be strong. We had to be good listeners. It was our turn to feel the pain, the losses. We were the only ones left with room in our hearts for the anguish. If we shared some of their pain, maybe it would make room in their hearts for joy and hope.

But, the truth is, I am not strong. The stories made me want to cover my ears before they were finished.

I feared that I was going to start hating the “enemy.” Why? My wife Jeanine and I always felt that it would be important to look the “Beast” in the eyes. I am convinced that the hate of war is not a beast; he looks just like me, just like you. He has a home everywhere. He lives inside every one of us. I am afraid! This is why I needed the strength of my Bosnian friends during my stay. They taught me not to hate, not to be manipulated by prejudice, to open my heart. The people in Bosnia-Herzegovina gave more sense to our lives than we could have ever given to theirs. The dilemma for me is how to show these images to the world without hurting or betraying the trust of the people who opened their hearts and their homes to us. I hope, with some luck, our friends have begun the healing process.

One Family, One Story

You walk into a friend’s home; it looks so very normal. You have some wine, talk about the cold weather, the children. The hosts joke about the missing parquet flooring–they had to burn it for heat along with their couch, table, chairs and clothing. We laugh about the way we gave the taxi instruction in the local language to get to their homes. Conversation never starts with a question. We don’t ask about the war.

You walk into a friend’s home; it looks so very normal. You have some wine, talk about the cold weather, the children. The hosts joke about the missing parquet flooring–they had to burn it for heat along with their couch, table, chairs and clothing. We laugh about the way we gave the taxi instruction in the local language to get to their homes. Conversation never starts with a question. We don’t ask about the war.

I can tell you about Jasmina, Samir, and their children. Our friends have two beautiful children; their names are Anna and Fouad. Anna had just turned eleven when we met her. She speaks a little English and Italian, has a great sense of humor, and is an extrovert. You would have to look very hard to see the effects of the war in Anna. She has decided to not let it interfere with her life. She is very strong. For Fouad, things are very different. The war started when he was four months old. Jasmina’s family lives in an area call Dobrinja, a suburb of Sarajevo. This neighborhood happened to be next to the airport, and it became a front line during the war. The Serb army surrounded the area and told the people of the neighborhood to leave their homes or be killed.

The people of Dobrinja a middle class bedroom community made a historic decision. They told the Serbs to go ahead and bomb them. They were not going anywhere. For the first six months of the two-year siege, Dobrinja was totally surrounded and cut off from Sarajevo. No food could come in. They had no running water, electricity, or gas to heat their homes in the winter. They were hit by artillery every day for six-months, non-stop–day and night. Snipers killed people gathering water at the river or cutting trees for fuel. They hit them with mortars as they worked digging the trenches that would allow them to move from one building to another without being shot.

Not everyone understood the danger. A group of children, tired of being locked in, sneaked out to play a game of soccer in an abandoned warehouse. When the Serbs heard the children playing, artillery stopped the game forever.

Jasmina and her husband Samir had to take cover in the basement of their apartment building, because they were taking direct artillery hits. You can still see a hole in their neighbor’s apartment. You could drive a bus through it–no problem. In this basement, all the tenants had their little storage spaces. This was to be their home for the next two years–four people in a space about four-by-five feet. Forget about lying down. Because of the broken pipes, water was ankle deep, so Fouad slept in his mother’s lap for two years. Fouad grew up in darkness listening to explosions, screams, chaos and crying. But he also learned about life and love. His curious mind was nourished by the many beautiful stories that were told by Jasmina and Samir. He also learned about songs and laughter. This was his world, an underground community, people helping each other, all in the same situation. A community always on the verge of hunger was being kept alive with 1963 Vietnam rations. Fouad grew up in this very cramped but intellectually nourishing environment. He was always held. His feet never touched the ground. It has been difficult for him to adjust to his new life–a world of light, open spaces, and individuality. Fouad’s imagination has been greatly stimulated. You can see it in his artwork. Slowly, he is opening himself to a world of light and space. He has inherited the gift of storytelling that most children his age will never learn, because they were born in the era of TV.

What was Samir doing during all of this chaos? He is a pharmacist by profession. Before the war, he had his own pharmacy. If you take a close look, Samir weighs about 140 pounds and looks very fragile. I have never seen him eat. He doesn’t have the muscles to meet the profile of the so-called “heroes” we are accustomed to seeing in U.S. movies. Dobrinja didn’t have a hospital before the war. They only had a dental and a first aid clinic. The community realized they had to organize and create an emergency hospital. When the shelling started, there was no place to take the wounded. Dobrinja was surrounded. No one in. No one out. Samir was in charge of collecting all the medicine available in the community. From shops to private homes, Samir collected medicine, avoiding being shot by snipers and artillery. He tells me that he has no idea what made him do this. “I am a very calm person. If, during the war, I would have had time to think about the bullets flying around my head, I don’t think I could have run between the buildings. I would still be in one of those trenches”.

The hospital was started in a shopping center. Doctor Youssef Hajir (I could write twenty pages just about his story) started operating on the wounded with dental tools. After two years of siege in Sarajevo, the doctor and his staff performed over10,000 major operations on only one operating table in Dobrinja. None of the patients developed an infection. If you consider the conditions under which the hospital was operating, it is a miracle.

The hospital was started in a shopping center. Doctor Youssef Hajir (I could write twenty pages just about his story) started operating on the wounded with dental tools. After two years of siege in Sarajevo, the doctor and his staff performed over10,000 major operations on only one operating table in Dobrinja. None of the patients developed an infection. If you consider the conditions under which the hospital was operating, it is a miracle.

The glass of wine and the wonderful smell of food bring me back from the war. Jasmina get ups and puts on some music. Before she fully returns to the present, she tells us about the time she decided to leave the basement in the middle of the night. She walked up to her apartment to look for her portable cassette player. It was the first time she had been in her apartment in two months, and she was putting herself in grave danger. Using the batteries from her flashlight, Jasmina decided that she must listen to Pavaroti. She felt that if this was not possible to do, she would go crazy and might as well die. So, at full volume–with the shelling and shots for background–Jasmina played a recording of an opera in her apartment while she sang along with the Maestro.

Once More, With No Feeling

Looking back, I wonder how much things have changed. Now we are watching the events in Kosovo, where more bloodshed is occurring, led by the same leaders who started the war. The European and American leaders are once again paralyzed by this. I have to wonder if we have learned anything at all. How many lives does it take for the international community to react?

Cemetery Harvest

One of my neighbors harvesting mushrooms and berries from the neighborhood cemetary.

Catholic Survival

An image from a Sarajevo cemetary in the middle of the city.

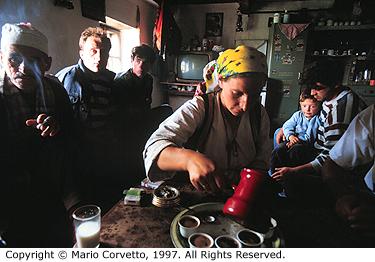

Coffee Grinder Lady

Grinding coffee in a farming community outside of Sarajevo

Coffee Time

Serving coffee is an important part of hospitality. This is an example of the openness of the people. Even though they suffered and their homes were destroyed, we were always welcomed with bread, cheese, and coffee.

Honoring the Dead

Everyday he came on his way to work and back. Right outside my dining room window a man acknowledges his lost relatives.

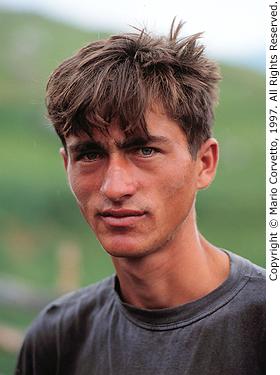

Igman Man

This man represents the face of young men who have seen to much. He had fought in the front lines.

Potato Lady

Portrait of a lady. In this community, the only help they wanted was to get tools and seeds. They did not want hand-outs; they wanted to work. They were a proud people and didn’t want to feel like beggars.

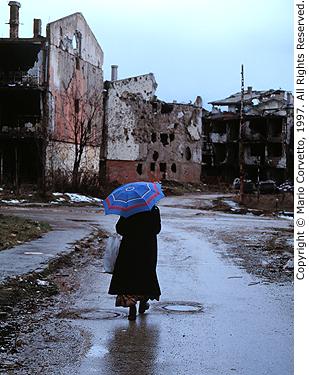

Save it for a Rainy Day.

When I first walked into this neighborhood, I felt that the people of this community would be tense and not very open. Instead they were very welcoming. It was as if they had waited for our arrival, as they would await a lost member of the family. It seemed to them that we had been gone for a very long time.

Two Franciscan Monks.

During the Pope’s visit, there was a very positive energy. The Pope brought a tremendous uplift to all of the people. It was more than a religious event. Muslim, Serbs, and Croats alike welcomed him.

The Mechanic

With help from the American Refugee Committee, this man was able to set up a shop for building and fixing wheelchairs. Although he was not injured during the war, he had found a place helping others who had been.

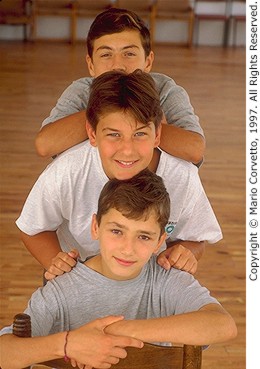

Three Kids

These kids saw their school being burned. When I photographed them, the school had been rebuilt. They were ready to go back to school and find their friends. This was taken in one of the youth clubs run by the Catholic Relief Services.

Art Students

These men are studying at an arts academy. Everything was destroyed during the war. Nonetheless there was an excitement about returning and continuing their studies, getting back into a routine, and being surrounded by fellow students.

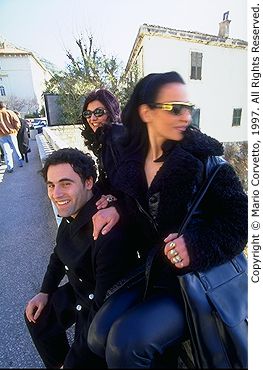

Leather Jackets

The Adriatic Coast. Young people could now dress up and congregate. The war was over.

by Mario Corvetto

Leave a Reply