Right here in front of me, I have a small pair of plastic tubes that I got back in the early 1950s. One tube is slightly longer than the other. Inside the tubes are thin brass reeds. When blown, the small tube mimics the high-pitched death squeal of the cottontail rabbit, while the larger tube produces the lower squeal of the jackrabbit. These were the first predator calls I had ever seen. Today, there are dozens of predator mouth calls on the market; my favorites are those made by Johnny Stewart, Haydell, Circe and the Burnham Brothers.

Although predators can be called in my home area of the Northeast, wildlife in the South, Midwest and Far West respond more readily to calls. It may be that, because the Northeast is more densely populated, predators are more wary. Also, the Northeast doesn’t have as many predators as the more rural and wilderness areas.

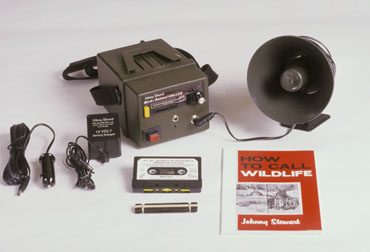

Today, more and more photographers are using electronic calls and calling cassettes. These are illegal to use for hunting because they’re actual recordings of the live species, and you just can’t get any better than that. But it is legal to use such callers for photography in most areas, although not in some national parks.

I have more than 50 calling cassettes produced by Gerald Stewart, Johnny’s son, that can be used to call just about any predator species in North America. The Stewart electronic caller has a detachable speaker and, by using extra lengths of wire, I can get it out about 75 to 100 feet from where I’m hidden. This is extremely important because you don’t want the predator looking at you; you want its attention to be diverted elsewhere, so you can move your camera when you have to.

Most of the calls are recorded squeals of prey species. The predators think that they can catch the prey species or that they can take the animal away from whatever did catch it. Although some predators may come galloping right in, most don’t throw caution to the wind. They come in very cautiously, very stealthily.

You don’t want to call on a windy day because the sound will be blown away behind you. You’ll have to sit facing the wind because many predators will circle the call trying to get the scent of whatever is making the call. That’s another advantage to the long speaker cord; in circling, the predator may pass behind you. You should photograph from a blind or dress completely in camouflage and have your camera covered, too. Place your blind or sit in front of a large clump of brush when possible so that you and the blind blend into the surroundings and aren’t silhouetted.

Some callers sprinkle fox or coyote urine or skunk scent near the speaker to help mask human odor. It also pays to give the predator something to look at in order to focus its attention away from you. Toy fur bunnies work okay, but the greatest device is the Rigor Rabbit put out by the Carry-Lite Decoy Co., a foam-molded rabbit that moves periodically. Its action is so lifelike that all kinds of predators, including hawks and owls, have been known to carry it off.

To be successful, you have to call in areas that your quarry frequents. You can ascertain this by observation, tracks, scat or by being told by the farmer or rancher whose land you have permission to be on. It’s useless to call in areas where quarry is heavily hunted; they become too wary to respond.

When you have everything set up and your settled in your you blind, wait least 15 minutes for everything to return to normal. The electronic game caller has a volume control; when you start to play the cassette, play it softly for about 30 seconds so as not to scare any predator that may be close.

If you don’t get a response in 10 minutes, turn up the volume a bit more and play it for another 30 seconds. Wait another 10 minutes. If there’s no response, turn up the volume full blast and let ‘er rip. If you still don’t get a response in 10 minutes, you might as well pack up and try another site.

If you spot a predator approaching, turn the volume way down and whisper a few more calls. The predator will hear it and the sound will keep its attention focused on the hidden speaker, which is where you want it to be. The noise of your camera shutter may alarm the incoming predator or it may be so engrossed in the call that it pays no attention.

Be alert for other species, as well; I’ve had deer, javelinas, hawks and an armadillo come in to a call.

Another reason to be backed up against a bush or tree is so that a predator doesn’t inadvertently stalk you. A number of hunters and photographers have been jumped by bobcats, coyotes and cougars in cases of mistaken a identity. Don’t call in areas frequented by bears and other potentially dangerous wildlife without taking the proper protective precautions.

A little less exciting, but a lot of fun, is to use the Stewart game caller, with its screech owl tape for small birds. With it, wind direction means nothing because birds can’t smell. Position yourself so that the light is favorable.

I place a dead branch or sapling in front of a brushy patch. The brush gives the birds a feeling of security because the owl they hear calling can’t get to them. The bare sapling gives the braver birds a place to sit, so you can get as chance to photograph them without a their being hidden by foliage.

Place your blind about 15 to 20 feet from the speaker, which I place at the base of the sapling. You don’t need to hide it as you would do when using it for mammals. I once had a Carolina wren land on the speaker and peer into the bell looking for the owl that it could hear, but couldn’t see.

Birds will mob an owl if they hear or see one during the daylight hours, putting forth a concerted effort in an attempt to drive it from the area before dark. Cardinals, flycatchers, jays, orioles, catbirds, thrushes, finches, wrens and sparrows are just a few of the species that respond readily to calls. Some photographers also place a papier-mâché owl in the sapling, but I’ve never found one to be needed. The call alone works very well.

On one occasion in Texas, while photographing scissortailed flycatchers that were responding to a call, a western kingbird landed on my head.

Never did get that photograph.

Try calling animals in; make your own action.

By Leonard Lee Rue

Leave a Reply