There are very few photographers who can go to an assignment without a camera in hand and still get work done. E. David Luria (“David” to his friends) is one of them. On a warm Saturday afternoon in March, Luria, 68, along with his co-instructor Dennis Ettlin, leads a group of nine amateur photographers on what he calls a “photo safari.”

There are very few photographers who can go to an assignment without a camera in hand and still get work done. E. David Luria (“David” to his friends) is one of them. On a warm Saturday afternoon in March, Luria, 68, along with his co-instructor Dennis Ettlin, leads a group of nine amateur photographers on what he calls a “photo safari.”

2

Luria came up with the idea for a “photo safari” in 1999. He noticed there were field trips for serious photographers but nothing for amateurs who wanted to learn how to take better pictures of their families or on vacations. Thus, he created the Washington Photo Safari to include sessions that ranged from two hours to all day, mostly during weekends and holidays. He took students around the District of Columbia to photograph monuments, museums, and neighborhoods.

3

He titled his first workshop “Monuments and Memorials,” directing students everywhere from the Lincoln Memorial to the White House. (A half-day workshop costs $69, and the full day version–which includes Adams Morgan–costs $119.) While each photography workshop has a different theme, students on this one take abstract pictures of the Adams Morgan area and its colorful and diverse architecture.

4

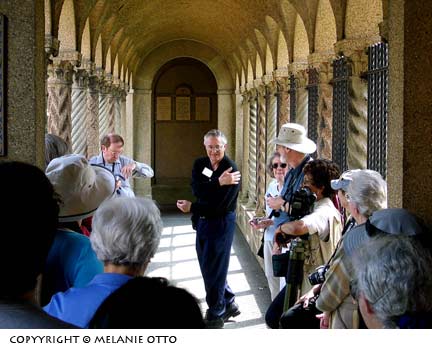

As the workshop begins, Luria hands out a sheet of photography guidelines, noting that this workshop encourages “out-of-the-box thinking and making pictures out of nothing at all.” Luria’s students range in age from the twenties to the fifties and arrive in sneakers, light jackets, and faded jeans, carrying bags of camera equipment slung across their shoulders. Luria keeps his hands free of equipment, so he can help individual students with their technique.

5

The first stop is Champorama Park on 18th Street and Kalorama. “That playground’s like a treasure trove,” Luria tells his group.

6

Soon the students scatter, some clustering around a mural, others focusing on the playground equipment. A red slide rests in the middle of the playground. To slide down it, you need to climb up the yellow steps and crawl through a purple tunnel. One student climbs the steps, crawls into the tunnel, and takes pictures of the steps from inside the tunnel. When she descends back down, Luria points to a piece of sky-blue string on the ground. “How about that?” he asks. The student squats and takes four consecutive shots of the string, leaning in closer to the ground with each shot.

7

Luria watches her for a second, smiling. Then he moves on to another student. She’s having problems holding the camera correctly. He tells her to make a “table” with her left hand as a base on which the camera can rest. “It’s fun to see people learn,” he says. But it wasn’t always easy for Luria. He became a full-time photographer when he lost his job at an international non-profit organization in 1995. During his first year as a photographer, his income fell by ninety-percent. Four years later, he started the Washington Photo Safari, but business was slow. His only advertising appeared at a local camera store. Then in 2000, he got his big break. He was featured on a segment of “The Today Show” about people who successfully changed careers late in life. “The segment was about late bloomers. I was 59 when I started blooming,” explains Luria.

8

Since then, Luria’s business has increased more than twenty-fold. He moved from six clients per month in 1999, to 140 clients per month in 2004. He has had 5000 participants since he began six years ago, including 1400 repeats, ten people who have taken ten safaris, and one person who has participated in forty-one. Phyllis Maguire, the veteran of forty-one tours, says she keeps coming back because of Luria. “I learn something new with each safari–whether it is inside or outside, daytime or nighttime, raining or sunny–and different subjects–people, buildings, paintings, etc. David’s classes are better than reading my camera manual.”

9

Maguire first participated in a session in September 2002, doing a tour of the monuments, which she says is still her favorite safari. Luria has a different recollection of their first session together. “I forgot to show up,” he tells us sheepishly. “ Then I got a call at 10 a.m. and raced down Connecticut Avenue at ninety miles an hour.’’

10

Back in Adams Morgan, Luria’s co-instructor Ettlin divides his time between helping students decide on focus and filters and taking pictures of his own. Ettlin participated in his first workshop two years ago. “Dave’s a great teacher and loves his art,” Ettlin says. Seeing Ettlin’s fondness for abstract photography, Luria asked him to co-instruct his class on abstract photography, and Ettlin has done so for the past year.

11

Luria’s clients on this safari are a mix of newcomers and old hands. One first-timer James Barnett says he never really tried his hand at abstract photography before. Barnett repeatedly adjusts his brown baseball cap and finally decides to wear it backward. He takes a picture of a broken notice board with its jagged glass edges and yellowing wood with nails and staples sticking out of it. He angles his camera upward and takes a picture.

12

Farther down the street, Carol Lawrence crouches to take a picture of a white metal fence, each metal bar twisted and shining like a piece of salt water taffy. An accounting professor on sabbatical, Lawrence says she participated in her first photography session last fall because it was the best way to learn about DC.

13

Midway through the workshop, in an unexpected turn of events, a group of motorcyclists stops and parks on 18th Street. “Oh, motorcycle heaven!” Luria exclaims before five students surround the motorcycles—some crouching, some leaning in toward the motorcycles, others standing perilously close to traffic. The motorcyclists wait on the sidelines, shaking their heads, their helmets in their hands, laughing at the scene.

14

The crouching on streets receives points, stares, and snickers. “ Is this going on exhibit?” one passerby asks. Another wants to know if the photographers are part of a television crew. Yet another man, who happens to be holding a camera, points it at the students, and grins.

15

“I tell people that they’re paparazzi in training. This is the struggle that artists face for their art,” Luria comments.

16

By the end of the two-hour session, all nine students have taken dozens of photographs of restaurant signs, fences, scrap metal, and doorways. Luria and Ettlin decide to walk half a block and pick up some homemade ice cream. Despite taking people to the same spots, week after week, Luria claims he hasn’t tired of the routine. “I’ve never thought of retiring—it would kill me, because I need to do something, and this is my something.”

by MISHRI SOMESHWAR

Leave a Reply