The place was Perkins Cove in Ogunquit, Maine, and my lobster had just arrived. An intimidating looking fellow with toothed claws and heavily armored carapace, he looked ready to battle the world.

My weapons bearer ceremoniously deposited a cheap nutcracker and two plastic picks at my elbow, wished me Godspeed, and departed. In my mind, a fanfare of trumpets sounded; the joust was about to begin. I knew I had only one small advantage, one slight edge. My opponent was dead.

In Toronto, far from its native haunts, Maine lobster is served grilled, boiled, broiled, stuffed, and pasted, and the restaurants charge an outrageous price. It arrives split, cracked, broken, and open.

You could serve it at the Queen’s garden party, and no guests need (horror of horrors!) lick their fingers afterward. Now, facing this knight of the ocean bottom, it was hard for me to know where to begin. Picture yourself preparing to tackle a Sherman tank, or its modern equivalent, with a can opener.

During this contemplative stage of my prospective meal, the fellow at the table next to mine ordered boiled lobster, with all the assured confidence of an expert. I waited for him to begin his dinner, hoping to copy his technique.

He cracked a claw, and so did I. He tore a tail, and I, as well. (Why don’t they equip these things with zippers?) He used his nutcracker, and I squirted lobster juice all down my shirt. He stopped for a smoke, and I twiddled my thumbs.

Finally, the meal was completed, my thumb bleeding only slightly. My adversary was reduced to a pile of empty armor, and a marvelous memory. So this was what all the fuss is about!

Seaside Ambience

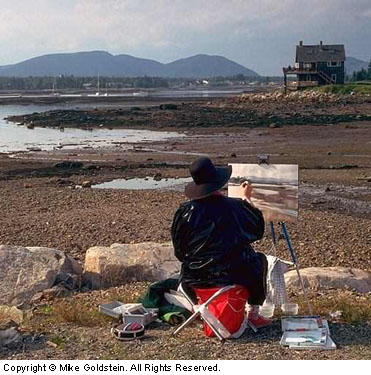

Being a photographer, I’m always up at the crack of dawn when on holiday, to catch the morning light. At sunrise, the only people around in Maine seem to be driving lobster boats, lifting or baiting lobster traps, or politely asking me what the #^*! I’m doing on their private lobster pier at such an ungodly hour.

I soon learned that, in every cove and gunkhole along the coast of Maine, it is not the cockcrow, but the thump of the lobster boat’s diesel engine, that starts the day.

On the Maine coast, there is an unusual way to render yourself alert for early morning photography, one never mentioned in the literature. You simply walk out to the end of the nearest lobster pier and inhale deeply. It is not the bracing salt air that awakens you in a hurry.

It is an assault on your nostrils caused by the aromas of yesterday’s baitfish, seaweed drying at low tide, and the effluvia of generations of seagulls. No wonder these young chaps who work here are such a hardy lot! … And they are young.

My image of the grizzled old-timer fisherman, his face lined with care and toil, quickly vanished. The only gray beard around the lobster piers seemed to be mine. (Was that why everyone was so polite to me?) Young the fishermen might be, but capable, as well.

No wasted motion, as they baited and loaded traps, fueled their boats, and tended their trap lines. I watched them for hours through camera lenses and binoculars, and their work was efficient through and through. Moreover, they seemed to be enjoying themselves.

Lobster piers offer a wealth of photographic opportunity. Inevitably, there are schools of dinghies, Zodiacs, and rowboats tied to them, their bowlines begging to be used as leading lines. Shooting down on them from up on a pier yields terrific pattern shots.

A polarizing filter will saturate colors and remove glare from the surface of the water. If the lobster fleet is in, (those elegant Cape Islander boats tied up, bow-to-stern), you can create interesting pattern shots of all the windows, or line up the bows of the boats with your telephoto lens. (Keep the sky out of the shot, and fill the frame with repeating shapes of boats.)

Colorful marker buoys adorn every wharf, catching the last rays of the sun, more brilliant still on a dark day.

Piles of traps throw tiger-striped shadows. There are coils of rope, rows of orange slickers, bright plastic bait barrels. It’s a wonder the lobstermen don’t have to work amidst hip-high heaps of artists and photographers.

The floats, or buoys, that you see everywhere are used to mark the location of each trap. When the trap is on the bottom, the buoy floats on the surface above it. Each fisherman has his own color combination and uses it on each of his buoys.

It’s the “brand” he puts on his “heifers,” Pardner. Each lobster boat carries a unique marker float, prominently displayed. This is not a status symbol or a banner, or intended to be a sign of membership in the distinguished company of lobster fishermen. It is a method of proving that the guy in the boat is hauling only his own traps and not his neighbor’s. Lobstermen may represent the last outpost of the “law of the open range.”

They’re known to solve their problems with vigilante justice, and woe betide the violator of accepted practice.

Follow the Gleam

One of the best ways to enjoy photography on the Atlantic coast is to “chase lighthouses.” Many of them are accessible by road; some will need a long lens to make them fill the frame. A boat cruise will sometimes take you within range of several.

For example, the boat cruise from Perkin’s Cove in Oguinquit will put you close to the Nubble Light. Remember to hand-hold your camera on a boat, as the hull will pass vibration from the engine to your tripod. It also rolls in the waves!

Often, Maine lighthouses are located close to picturesque fishing villages, complete with cozy restaurants, microbreweries, and tiny hotels. Photographers can easily create memorable vacations simply by trying to visit every lighthouse possible.

Lobsters Have Agents?

Tyler Hodgdon is a supervisor at Robinson’s Wharf, just outside Boothbay Harbor. Here, at a lobster agency, he told me how lobster is purchased from incoming boats.

The agency will pack them for you to take away, sell them to local restaurants, and/or ship them further afield to places like Boston and New York City. They’ll even store them, live, in a fenced-off cove, where up to 80,000 lobster might consume fifteen bushels of fish per day.

They pay the lobsterman up to three dollars per pound. On the same wharf, I paid eight dollars and fifty cents for a steamed lobster lunch, complete with a bag of potato chips and a cob of corn. That was the lowest price I paid for a lobster dinner in Maine. Usually, a lobster roll alone costs that amount.

Why does the lobsterman work so hard, if he sees himself with such a small share of this very lucrative market?

If he talks to you at all, he’ll tell you he works for the satisfaction of being an independent businessman. He is his own man, doing a job that might be traditional in his family, often with gear he builds and maintains himself. He will probably not tell you that part of the reason he stays is the challenge of wresting a living from the sea, but challenge has always attracted mankind.

The next unzipped crustacean I encounter on my plate will represent a small hazard compared to those faced by the men who “go down to the sea in ships.”

Trolley Trips

“Clang, clang, clang went the trolley; ding, ding, ding went the bell…” Standing on Shore Road in Ogunquit, Maine, you can almost believe that old song was written here. Every few minutes, from early morning to late evening, a “ding” and a “clang” announce the arrival of public transport.

Painted a fiery red and covered with local advertisements, Ogunquit’s trolleys are a tourist attraction in themselves. They’re not really trolleys, as they have internal combustion engines, and they go down tiny lanes and through hotel parking lots in the course of their travels. However, in shape, sound, and spirit, they’re the essence of a turn-of -the-century trolley car, and that’s what they’re called.

Toddlers stand, all agog, as the big red trolley pulls up. Customers climb aboard and pay their twenty-five cents to ride across town, to travel several stops, or to do a complete loop as a town tour. The drivers provide a constant barrage of commentary on the habits of other drivers and the crowds of pedestrians, as well as a wealth of local lore. “I work a seven hour day.

I’ve done it for five years, and I love it!” Sue, the trolley driver, told me how the town of Ogunquit initiated the trolley scheme to relieve traffic congestion during tourist season, and that it was an immediate success. Amazingly, the low fares cover all operating costs, including driver salaries. The trolleys are that popular.

The trolley route extremities are anchored by Ogunquit’s two main attractions, Perkin’s Cove and the beach. Perkin’s Cove is a small inlet at one side of the town, filled with boats and flanked by restaurants, tourist shops, and galleries.

It’s a successful Maine-style blending of the lobster industry and the tourist industry. Fishing and tour boats must navigate a minefield of lobster trap buoys that dot the little harbor, while lobstermen returning with their catch in the late afternoon rub shoulders with visitors carrying sling bags and cameras.

In Perkin’s Cove, you can buy a lobster trap, hire a fishing boat, take a cruise to the Nubble Lighthouse, or just relax and browse the art and antique galleries.

The Cove is a photographer’s delight. A thousand “still life” compositions may be found on a ten-minute walk. (Use a little flash fill for “people shots” on a sunny day, to chase those dark shadows.)

For the less sedentary, Ogunquit’s famous Marginal Way offers a walking tour right along the coast. This shoreline route, over a mile in length from the downtown area to Perkin’s Cove, was built over forty years ago. It’s great to arise in the very early morning and walk from your motel or guesthouse along the Way to Perkin’s Cove.

Seagulls hover, the air is sweet with the aroma of wild roses, and the ebb and flow of the sea is at your feet. At the end of your walk, a grand breakfast, alfresco, awaits you at Jackies Too, a charming eatery with a very large patio right on the shore. The light reflected from the water is brilliant, and the morning sun is already hot enough that you welcome the shade of the canopy.

“Anyone for Roberto’s? The Marginal Way? Ogunquit Square?” The trolley drivers call out each stop, which can include favored restaurants, shopping areas, and even the larger hotels. Parking is costly and hard to find. Only the local bloods drive in this town, doing the usual small-town cruise in the evenings.

A fun way to photograph the trolleys at night is to fire your flash at the front of the trolley as it goes by, then “drag the shutter,” on a time exposure, letting the brightly lit windows and colorful lines along the hull burn onto the film.

Ogunquit Beach, the other star attraction, is the terminus of each trolley route, featuring breakers large enough for surfing, hard-packed sand ideal for jogging and walking, and miles of beach to accommodate the largest crowds.

When the tide is out, you might encounter a “speed sailor,” which looks like a windsurfing sail installed on a large skateboard. Strangely enough, true windsurfing does not appear to be a popular sport here. (Break the horizon with the people you photograph here, and try to make the shoreline into a diagonal that splits the frame. Be careful of using auto-exposure, as there’s lots of glare from the water and the sand.)

My journey continues on the Victory chimes….

by Michael Goldstein

Leave a Reply