Eureka! Gold! With that cry in 1849, the rush for riches was on. Today, remnants of towns and communities from this rough-and-tough time are scattered throughout the West. Most are related to the great gold rush and mining booms of the westward expansion. Many are in various states of decay; some in stages of “rebirth”; others are preserved and protected; and a limited few have been turned into tourist/amusement-park attractions.

Eureka! Gold! With that cry in 1849, the rush for riches was on. Today, remnants of towns and communities from this rough-and-tough time are scattered throughout the West. Most are related to the great gold rush and mining booms of the westward expansion. Many are in various states of decay; some in stages of “rebirth”; others are preserved and protected; and a limited few have been turned into tourist/amusement-park attractions.

In California and western Nevada, it is possible to travel the routes the forty-niners walked as they searched for that ever-elusive glory hole. With a little patience and a discerning eye, photographers may be lucky and find what they are looking for.

Unless otherwise noted, all of the towns and sites mentioned in this article can be reached via paved or graded gravel roads. Good advice is to check with locals for weather and road conditions before traveling off the main roads. Distances between accommodations, food, water, and gas are vast in Nevada, so it’s always wise to fill up whenever possible and carry emergency supplies.

WESTERN SIERRA NEVADA AND MOTHER LODE COUNTRY

Highway 49 follows the main gold trail in the Mother Lode as it winds between the old mining camps and towns among the western foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Once a quiet byway, today this busy highway still meanders through rolling hills of oak and pine. Roughly divided into three sections, the Mother Lode can be traveled as short day trips or as an all-inclusive extended excursion.

The southern section begins at Oakhurst (at the Junction of Highway 41, one of the gateways to Yosemite National Park), and continues northward for approximately 57 miles through many small settlements. Mariposa, a good headquarters for exploring this section of Highway 49, is a typical town mixing the new with many Gold Rush relics. Take the side loop road off Highway 49 to Hornitos. At one time it had a population of 15,000, and was one of the most noted of the “hell-raising” towns in the Mother Lode. Today it is very rural, with ruins and parts of buildings that speak of its past. The road into this small, beautiful valley has several steep and winding sections, but it is paved all the way.

The southern section begins at Oakhurst (at the Junction of Highway 41, one of the gateways to Yosemite National Park), and continues northward for approximately 57 miles through many small settlements. Mariposa, a good headquarters for exploring this section of Highway 49, is a typical town mixing the new with many Gold Rush relics. Take the side loop road off Highway 49 to Hornitos. At one time it had a population of 15,000, and was one of the most noted of the “hell-raising” towns in the Mother Lode. Today it is very rural, with ruins and parts of buildings that speak of its past. The road into this small, beautiful valley has several steep and winding sections, but it is paved all the way.

The central section of the Mother Lode contains the majority of the mining camps. Sonora and Angels Camp are small cities with many remnants of their rough beginnings intertwined with modem-day businesses. Each Mother’s Day, Sonora hosts the annual Mother Lode Round Up and in July, a Mother Lode Fair. Angels Camp is the site of the annual Jumping Frog Jubilee during the third week of May. Frogs are painted on the sidewalks, and the main street is festooned with “unmentionables” from the era gone by

Columbia State Historic Park, a restored and preserved gold-mining town, is a major attraction in this area. It is a living museum of the past, with the main street closed to traffic. Enjoy the old buildings, stagecoach ride’s, shops, and shopkeepers dressed in the costumes of the Gold Rush heyday. Self-guided-tour pamphlets are available at Park Service headquarters.

In the vicinity of Jackson are several short side trips Off Highway 49. Mokelumne Hill has an old hotel worth a night’s visit that boasts of a ghost. Volcano, Fiddletown, and the Indian Grinding Rock State Historic Park all provide interesting glimpses into the past.

In the vicinity of Jackson are several short side trips Off Highway 49. Mokelumne Hill has an old hotel worth a night’s visit that boasts of a ghost. Volcano, Fiddletown, and the Indian Grinding Rock State Historic Park all provide interesting glimpses into the past.

North of Placerville is the Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park. It is near here that gold was discovered in 1849. A replica of the original mill is located here, however, the actual site of discovery is a short distance away (the river has changed its course over the years). The museum, normally open 8 a.m. to sunset, is excellent, and gives a good orientation to the gold-mining process. Opening times for other buildings vary with the seasons. Although summers can be hot and crowded, spring and fall are lovely.

In the northern section of Highway 49 are the communities of Auburn, Grass Valley, and Nevada City. Auburn and Grass Valley are modern communities, with several well-preserved buildings and historic landmarks. Among the points of interest are the Northstar Powerhouse Mining Museum and the Empire Mine State Historic Park. Both are worth seeing, and either have a small admission fee or ask for a donation.

The main section of Nevada City boasts of working gas lights. The National Hotel claims to be the oldest continually operated hotel in California. Rooms are furnished in antiques, with a lovely dining room and historic tavern. While meandering through town and along side streets, you’ll discover good restaurants, nice shops, bars, and places of interest, which have retained the feeling of an earlier era.

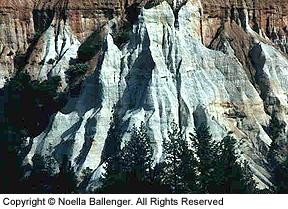

Not to be missed, albeit harder to find, are North Bloomfield and Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park. Best access is via Tyler-Foote Crossing road which junctions Highway 49 approximately 11 miles north of Nevada City. The first 15 miles are paved. After that, it is intermittently paved and graded gravel (with the road name changed to Cruzon Grade Road). Driving one way will take approximately one hour. Here, in the 1860s, in the world’s largest hydraulic gold mine, huge water cannons (called monitors) were used to wash away mountains, which created a man-made Grand Canyon and lake. Downstream, the mud-and boulder-choked water wreaked havoc on fields and farms. The constant threat of floods and silt-filled shipping lanes in the Sacramento delta caused concerned citizens, as far away as San Francisco, to fight the miners. After a ten-year struggle, laws were passed outlawing hydraulic mining, and forcing the closure of this site.

Not to be missed, albeit harder to find, are North Bloomfield and Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park. Best access is via Tyler-Foote Crossing road which junctions Highway 49 approximately 11 miles north of Nevada City. The first 15 miles are paved. After that, it is intermittently paved and graded gravel (with the road name changed to Cruzon Grade Road). Driving one way will take approximately one hour. Here, in the 1860s, in the world’s largest hydraulic gold mine, huge water cannons (called monitors) were used to wash away mountains, which created a man-made Grand Canyon and lake. Downstream, the mud-and boulder-choked water wreaked havoc on fields and farms. The constant threat of floods and silt-filled shipping lanes in the Sacramento delta caused concerned citizens, as far away as San Francisco, to fight the miners. After a ten-year struggle, laws were passed outlawing hydraulic mining, and forcing the closure of this site.

EASTERN SLOPE AND NEVADA GHOST TOWNS

The Eastern Sierra Nevada slope and western Nevada ghost towns are quite different than those seen in the Mother Lode. Instead of rolling hills and forested areas, they are found in high sage, basin, and range territory. in Nevada, there is hardly a true ghost town remaining. Today, you are more apt to see remnants of the old alongside the new. Modem mining techniques permit reworking old sites at a profit.

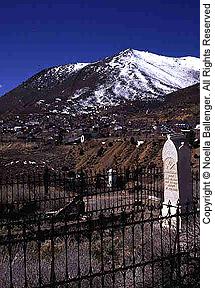

Virginia City on Nevada State Highway 17, close to Reno and Carson City, is an example of an old mining town, restored and commercialized, and now expanded by new workings. The original open pit at the south end of town has been re-mined and expanded, and stretches alongside the road toward Gold Hill and Silver City. The laughter and noise from the summer crowds are reminiscent of the boom days of the Comstock Lode, when miners, gamblers, and painted ladies walked the boardwalk. Other places of interest include Piper’s Opera House, the Mark Twain Museum of Memories, and the Castle. The historic cemetery is a must. You can only speculate upon the citizens of Virginia City who lie buried there. If only tombstones could talk!

Virginia City on Nevada State Highway 17, close to Reno and Carson City, is an example of an old mining town, restored and commercialized, and now expanded by new workings. The original open pit at the south end of town has been re-mined and expanded, and stretches alongside the road toward Gold Hill and Silver City. The laughter and noise from the summer crowds are reminiscent of the boom days of the Comstock Lode, when miners, gamblers, and painted ladies walked the boardwalk. Other places of interest include Piper’s Opera House, the Mark Twain Museum of Memories, and the Castle. The historic cemetery is a must. You can only speculate upon the citizens of Virginia City who lie buried there. If only tombstones could talk!

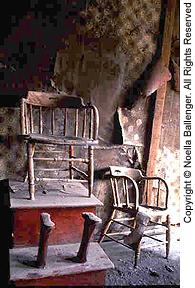

Driving south on Highway 395 in California, at the turnoff for Bodie, pull out and stop at the road edge. In the canyon to the west are slag piles, and heaps of rock which mark the site of Dogtown, a wild and short-lived mining town. Turn onto California State Highway 270 to Bodie. This historic park is the crown jewel of ghost towns. It is unique in that it is preserved in a state of arrested decay, and not restored or commercialized. Be sure to take food and beverage with you, as no services are available. A guided tour of the Standard Stamp Mill is offered twice daily during the summer. It is free, but tokens must be obtained at the museum.

Four-wheel-drive enthusiasts will enjoy taking the road out of Bodie to Aurora, once the county seat of Mono County, California until surveyors discovered it was in Nevada. Today, only traces and ruins remain of this once-prosperous gold camp. However, in contrast to the old, several working open-pit, heat-leach process gold mines are visible in the canyon approaching Aurora. This is a good place to contrast with the new what little remains of the old.

Several interesting ghost-town loops center around Tonopah, Nevada. Its mountains once produced millions in silver, and while it remains an active mining center today, it still sprouts signs of old mines and mining equipment. The old Mizpah Hotel is a sight to see. Memorial Day brings parades, mining contests, and burro and camel races.

From Tonopah, continue east on Highway 6 to state route 376. Turn north, and continue approximately 13 miles to the turnoff for Belmont. Continue approximately 27 miles on this sometimes paved, sometimes gravel road to the town. The stone and wood buildings are in various stages of collapse, but the photographer will find them fascinating. Most are fenced and posted “No Trespassing” for safety’s sake. Textures, edges, and details provide a special opportunity to use your long lenses to get “close.” The old courthouse is still intact and in the process of restoration. Continue north through the town to the mill ruins at East Belmont. A large, brick furnace tower and several massive sections of mill walls remain.

Backtrack through Belmont for about four miles until you see the turnoff for Manhattan. A ten-mile drive on a graded, gravel road, first through sagebrush then pinyon pines, will take you to Manhattan, a town of both old and new mining. The wooden church on the hill came from Belmont, by wagon, when that town closed down in the early 1900s. It is here in the narrow canyon that today’s collection of small houses and trailers are reminiscent of the early boom-town days. Rejoin state route 376, and retrace your path to Tonopah.

From Tonopah, go south on Highway 95 to Goldfield. Again, old and new mining mix in this sleepy county seat. There are several stone buildings, some still in use, that are quite magnificent. Look for the old bottle house on the main highway near the center of town.

Continue south for about 15 miles to the junction of Highway 266, the Lida road. Turn west, and drive approximately 12 miles until you come to a road with a sign reading Goldpoint. Goldpoint is about 10 miles south of 266, on a good, graded dirt road. There are many buildings in various stages of repair, slag heaps, and old mining equipment. The town was originally named Hornsilver, but was changed to Goldpoint by promoters in 1929.

Continue south for about 15 miles to the junction of Highway 266, the Lida road. Turn west, and drive approximately 12 miles until you come to a road with a sign reading Goldpoint. Goldpoint is about 10 miles south of 266, on a good, graded dirt road. There are many buildings in various stages of repair, slag heaps, and old mining equipment. The town was originally named Hornsilver, but was changed to Goldpoint by promoters in 1929.

Return to Highway 95, and continue to Beatty and Rhyolite. Rhyolite, a true ghost town in every sense of

the word, has seen dramatic changes in atmosphere and spirit in the past five years. The buildings have all been put off limits by a caretaker. A new, open-pit gold mine is being worked on the hill between the highway and town. In spite of this, it is still possible to view the old ruins, the glass bottle house, and railroad station from the main street.

The old store and museum at Bullfrog, just around the corner from Rhyolite, is nice to visit. The owner carries a very good assortment of booklets on ghost towns and mining.

The old store and museum at Bullfrog, just around the corner from Rhyolite, is nice to visit. The owner carries a very good assortment of booklets on ghost towns and mining.

Just west of Rhyolite is the turnoff for the Titus Canyon entrance to Death Valley. This one-way road, recommended for four-wheel-drive vehicles only, has steep grades and beautiful vistas. At the bottom of the canyon are tight, shear cliffs. Do not drive this road if flash-flood conditions exist. About halfway down the canyon is the encampment of Leadfield. Started in 1925 as a promoter’s hoax (the area having been salted with Tonopah ore), a few buildings remain.

Leave Death Valley by the southern route, to Baker, and drive back along Interstate 15. The ghost town/ amusement area of Calico (well-signed from the highway) is located north and east of Barstow. In the late 1800s, Calico was a large silver-mining camp. Today, it has been completely restored, and is now a Mecca for tourists, with its many curio shops, museums, and excursions into the mine.

NOTE: Because of the sensitivity of many areas where ruins, old mines, sites, and buildings are found, a word of caution is necessary. Much of what you will see has been severely abused by tourists, and looted by souvenir hunters. Strangers may not be looked on kindly, regardless of good intentions, or the camera in hand. Be a considerate guest. If the area has been posted: Do Not Trespass, use your long lens instead. Do not remove or disturb what you find-leave it untouched for those who follow.

PHOTO TIPS

In our search for ghost towns and relies of the past, we were either overwhelmed by what we found or exasperated by what we didn’t find. When photographing a site, our suggestion is to start out small. Concentrate on textures, patterns, and details. Once you get a feel for the minute, expand your point of view by using wide-angle lenses, and eventually look for the overview that will convey the essence of the place.

The strongest photographs are usually simple. You should therefore eliminate all but the essential. It’s better to take several photographs than to try to cram everything into one picture. Use different lenses to tighten your composition, and change your camera position for a variety of angles and lighting effects.

We planned ahead, estimating our driving distances, to give ourselves time to see and photograph in the “right” light. It wasn’t always possible to control where we were at the optimum time of day. We found that judicious cropping of scenes helped to eliminate the bright noon skies of summer, or the gray skies of winter.

Traveling the ghost-town trail gives the photographer the opportunity to express through images how the men, women, and children pioneered our west. Walking back in time to capture the sense of wildness, jubilation, despair, and hardship, as well as a sense of time and place, is a challenge well worth the effort.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION

There are excellent books available to assist you in traveling the ghost own trails. Our favorites include:

The Mother Lode, Automobile Club of Southern California, 1989; Ghost Towns of the West, by William Carter; A Sunset Pictorial, Lane Publish ing, rev. 1978; Sunset Gold Rush Country, Sunset Books, Lane Publishing Co., 1989; California-Nevada Ghost Town Atlas, by Robert Neil Johnson, Cy Johnson & Son (Box 288, 435 N. Roop Street, Susanville, CA 96131).

This article first appeared in Petersen’s Photographic magazine, September 1990. Please be sure to check with locals for road conditions or changes since this article was written.

by Noella Ballenger and Jalien Tulley

Leave a Reply