The telephone rings; it’s Gourmet Today Magazine. They want me to spend time in Touristown, USA, photographing selected upscale eateries for them.

They’ve booked me into one of the classier B&B establishments for a few days, one located in the artists’ colony of town where the target restaurants are located.

As I pack my camera bag, I’m already thinking about other photo markets for shots I might do on my own time–artists’ studios, local hotels and inns, and–of course—bed-and-breakfast accommodations.

Most of these images will be interiors, so I take a moment to consider lighting and lenses as I pack. Later, on site, I’ll think about “the look.”

LIGHTING

The village church in East Barnard, Vermont follows New England tradition in being open all day, year ‘round,even when nobody is in attendance. The late afternoon light coming through the west windows makes the classic interior glow. As I wanted the light to follow the “leading lines” of the pews, no other lighting was used for this image. A 24mm lens was used here.

It would be great if this were a “no holds barred” kind of shoot, with time to set up multiple light stands and have total control of the lighting. In fact, this will be more of a “lightning tour,” with the restaurants in question fitting me in when and as they can. I expect to use a flash and pray for large windows and a low white ceiling.

I once shot a San Diego restaurant next to a marina using only the equipment I was carrying in a belt bag, and employing a monopod for camera support. Doing the restaurant shot was a very unexpected bonus to a day of walking around outdoors.

I balanced window light against interior lighting and bounce flash (un-metered!), and used my 24mm lens with the polarizer removed. We tidied up the target area, the restaurant produced a bottle of red wine and a cooked meal on amazingly short notice, and the resulting image was published twice!

With a more advanced notice this time, I pack my flash meter. Depending on automatic exposure of flash or camera makes me nervous when clients depend on me. I try to take interior shots on a bright day. I meter the room interior, with all possible lighting turned on, and that establishes my basic exposure.

Using a tripod allows me to opt for maximum depth of focus. Then, I measure the window light, actually pointing the camera through the window. If I’m lucky, the exposures are close, but often, I must allow the window light to overexpose.

However, I can usually “pump up” the interior exposure by bouncing my flash from a low, white ceiling or even a wall, to the point at which the two exposures are close. Bounce flash yields even, shadow-free lighting, so that you can rarely tell that flash was used.

Even if I’m using the features of a modern automatic flash (see my Apogee Photo article, “Intelligent Sunshine”), I like to check the flash exposure with the flash meter.

I use only outdoor daylight film for my interior shots, because the cozy warm glow caused by incandescent lighting on this film yields a nice effect that people like. I avoid fluorescent lighting like the plague. (“Fluorescent lighting, in my restaurant, M’sieur?”) Even an FLD filter can’t make it look warm.

LENSES

My “bed & breakfast” in Touristown, USA (actually photographed in Niagara Falls, Ontario) offered a bedroom ideal for photography. The strong window light was muted by pulling down the shade, and balanced against the light of several lamps in the room. Flash was bounced from the white ceiling. The corner of the bed, and the corner of the ceiling, give opposing leading lines, which make for a rather neat composition. I used a 17mm rectilinear lens for this photograph.

No need to pack long lenses for this shoot. Room interiors demand the use of wide-angle lenses, if you want to achieve a look of spaciousness. A 24mm lens is good.

The wide-angle zooms are extremely versatile for this kind of shooting. My favorite is my 17mm rectilinear wide-angle lens, which consistently allows me to photograph my own tripod legs, if I’m not careful. Use of wide-angle lenses usually requires that you be cautious about tilting the lens up or down indoors, to avoid the perspective distortion of leaning walls.

No need to pack lots of filters, either—except, perhaps, a color-correction filter (like the FLD), if you’re faced with fluorescent lights.

While you can use “indoor film,” I’ve never published an interior image with that film palette. Manual focus of lenses is usually a requirement for interior photography, with “depth of field preview” a necessity, to check that everything is in focus.

THE LOOK

Producing publishable restaurant photographs is not easy. Unless you bring your own professional models, and/or you’re handholding “grab shots” of the entire room at night, avoid including diners.

Blurred shots of waiters in motion can be effective for mood, but you have little control over the process or the resulting compositions. However, shooting diners at night can be effective, if you can shoot down on them from on high, using a “bird’s eye view.”

This gimmick works well if the floor has a distinctive pattern or if the tables are circular.

If you can shoot while the restaurant is empty, you can usually coax the owners into providing props–a bottle of red wine and a cooked meal. They won’t mind if you move things around a bit. Corral a waiter or two to assist you.

Try to isolate one table, with an outdoor window scene as your background. Angle the table so one corner is facing the camera; the sides of the table make great leading lines. Shoot a round table from a high angle with a wide lens, to emphasize its roundness and space for happy diners. Use plants, trees, and any color accent you can find to avoid that monochromatic look.

You can make a room appear larger by including mirror reflections where possible. If you can shoot only a mirror reflection of a room (like shooting only the reflection of the building’s exterior in a puddle), you’ll produce an unusual perspective that will capture attention.

When I’m shooting in museums or historic buildings, I try to make portraits of people in period costume, shooting only their reflection in a window or a mirror.

Most artists and artisans will happily pose with their creations, allow you to photograph them at work, and happily accept your offer of free shots for their advertising. (Ask for a photo credit!) Check the studio lighting, as it’s often the dreaded fluorescent.

Bounce flash is just as useful in this environment, where you’ll often be unable to set up your tripod. If your location is a hotel room or bedroom, treat them like restaurants. Use the corner of the bed in your foreground and make use of mirrors and window scenes.

My hostess at the Touristown B&B was amazed. Before I had even unpacked my suitcase, I set up my tripod and photographed my bedroom in the soft afternoon light!

More Photos and Captions

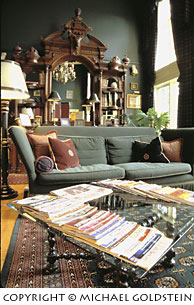

The lounge of the Ripplecove Inn, in Québec’s Eastern Townships region, made a challenging photograph. This is actually quite a dark room. The strong window light was offset by one lamp in the composition, and all other interior lights were turned on.

The ceiling was far too high for bounce flash, so direct flash was used, allowing the natural flash “drop off” to pick up the dark woods on the far side of the room. The magazine table, angled to present a corner to the camera, provides nice leading lines into the room.

This is a situation that does not demand a human figure, but is actually a portrait of the room itself.

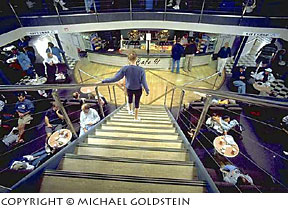

“The Cat” is a catamaran car ferry that is operated by Bay Ferries, from Bar Harbor, Maine, to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and which saves NS-bound motorists a full day’s driving. “Our way or the highway”, claims Bay Ferries, who offer a “two nation vacation”!

Not much control over lighting in this image, which was made using a 17mm rectilinear lens, hand-holding the camera.

The stairway and its rails offer great leading lines, pulling the eye to the figure, and beyond, and implying great space, a novelty in a boat! 24mm and 17mm lenses offer almost infinite depth of field, and the ability to hand-hold a camera with quite acceptable results in low lighting.

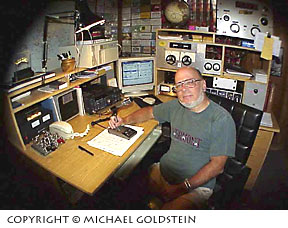

This portrait, of a radio amateur in his station, uses the corner of the operating table as the source of leading lines.

The perspective distortion, caused by using a very wide 14 mm lens, lends an unusual feeling to the image. The vignetting, which was unintentional and still not explained, added to this effect, and was retained.

Several desk lamps were used to direct light into the operating area, while flash was bounced from the low overhead ceiling.

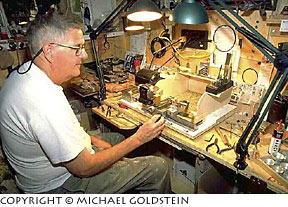

George James, the “Model Maker of East LaHave”, builds the most exquisite ships’ models you can imagine, in his tiny garage workshop in south-shore Nova Scotia, selling each one for the price of a top-line digital camera, and filling orders from all over the world. However, he hasn’t set up his workshop to be easily photographed!

I had George turn on all his available lights, and I filled in the foreground lighting on his shirt with metered fill flash.

The image was made using a 24mm lens and a hand-held camera, and I tried to portray the “ordered chaos” of an artisan who turns his own brass cannon on a jeweller’s lathe, colour-codes his tools, and works to a meticulous schedule.

This composition was made in the “La Grappe du Vin” restaurant cum wine bar, in Mont Tremblant, Québec. Window lighting, and the minimal interior lighting, was augmented by direct flash, bounced from an on-flash bounce card.

A 24mm lens was used, hand-holding the camera, and then I went back to one of the great lunches of my lifetime!

Here is a lighting challenge of the first order! Very little in the way of interior lighting, dark wood on walls and ceiling prevent the use of bounced flash, and a large window to reflect any direct flash back into the lens. Hmmm …

In the end, I exposed for the window light by pointing the camera through the window, then set my aperture to overexpose by one stop, hoping the slide film’s contrast range would bail me out. Essentially, only window light is being used here, and I moved the table and chairs as close to the window as I could. (Photographers make images!)

by Mike Goldstein

Leave a Reply