Copyright © David Johnson

Camille Howard sing the blues,

Primalon Ballroom,

Fillmore District, SF, c. 1950

At age 83, David Johnson shoots straight and strong. A professional and accomplished photographer, he is also a multiple role model. He made a boyhood passion and dream his reality: to become a photographer, the first African American to study with Ansel Adams at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. Johnson is fulfilling his declared mission and has become a primary photographic chronicler of African American life.

He is a man who has risen above extreme prejudicial treatment as a child growing up in Jacksonville, Florida, and an adult in San Francisco in the 1940s and 1950s. And he is an octogenarian who sees no limits to chronological age. Johnson continues his drive to learn and create, excelling at his profession, mounting frequent shows, and sharing his expertise and wisdom with younger artists.

Fueled by his love of photography Johnson broke a racial barrier at age 19 in 1946. Living in Jacksonville, he saw an article in the local paper announcing that Ansel Adams, already a nationally renowned photographer, would head the photography department at the California School of Fine Arts. Johnson wrote to Adams, requesting permission to join the class and stating that he was a Negro. In Adams’ reply, he admitted Johnson to the school and added that his race did not matter. When Johnson enrolled, Adams welcomed him into his home, where Johnson lived during his photographic studies. Adams counseled him early, “Photograph what you know best.” This wise advice led to Johnson’s enduring and wide-ranging chronicling of African American life.

As the selected accompanying photographs attest, Johnson’s photographs document African American culture of the last six decades, including the civil rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s and the poignancy of daily life. His work also celebrates individuals in politics and culture. When employed by a local newspaper, he photographed many celebrities, including Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, Paul Robeson, Jackie Robinson, and the poet Langston Hughes. He also captured entertainment idols, such as Nat “King” Cole, Eartha Kitt, blues singer Ruth Brown, and jazz guitarist “T. Bone” Walker.

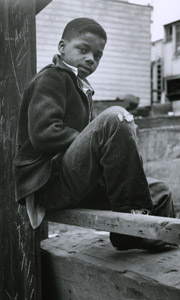

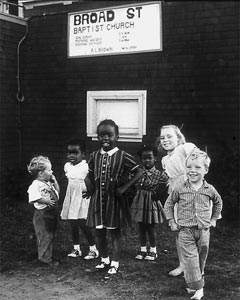

Equally compelling are Johnson’s images of ordinary African Americans. These speak today—a young boy sitting pensively on a fence; weary civil rights marchers in Washington, DC; a father watching his daughter on a carousel. As forceful are images of a man lounging in a shop doorway, proud deacons at a storefront Baptist church, and children of two races delighted to pose together, oblivious of their different skin colors.

Copyright © David Johnson

Boy sitting on a fence, Fillmore District, SF,

c. 1950

Copyright © David Johnson

Man at Carousel

Copyright © David Johnson

Black and white children,

Broad Street Baptist Church

When young Johnson arrived in San Francisco after World War II and a stint in the U. S. Navy’s segregated Stewards Department (for “colored” people only), he moved to the Fillmore District. In this area, an African American population had relocated from the Southern states to seek work in war-related industries, and the Fillmore became their accepted neighborhood.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the Fillmore District became a mecca of African American jazz, attracting such stars as Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Billie Holiday. Johnson has always loved jazz, and he started visiting them and photographing what he saw. In clubs that were long famous but have sadly vanished (such as the Blue Mirror, Jack’s Tavern, and Primalon Ballroom), his photographs document the vibrancy and joy of the music and nightlife. We see Camille Howard singing the Blues (lead photo above) and a couple dancing on Saturday night.

Copyright © David Johnson

Couple Dancing, Fillmore District, SF,

c. 1951<style=”font-size: 10.0pt; font-family: Georgia”>

The Fillmore District, currently undergoing massive urban redevelopment, is regaining its reputation as the historical jazz center of African American culture. It is now officially the Fillmore Jazz Preservation District, and Johnson’s role in preserving the District’s history is acknowledged in a PBS documentary about San Francisco. And at the Gene Suttle Plaza, an inscription with Johnson’s name is engraved into the sidewalk alongside other important African American figures.

Johnson is the only living photographer represented in the book Harlem of the West: The San Francisco Fillmore Jazz Era (Elizabeth Pepin and Lewis Watts, Chronicle Books, 2005). His images are featured in several other books, including San Francisco’s Lost Landmarks (James R. Smith, Word Dancer Press, 2004) and The Moment of Seeing: Minor White [Johnson’s acclaimed mentor] at the California School of Fine Arts (Stephanie Comer, Deborah Klochko, and Jeff Gunderson, Chronicle Books, 2006).

Copyright © David Johnson

<style=”font-size: 10.0pt; font-family: Georgia”> Paraplegic man on skateboard<style=”font-size: 10.0pt; font-family: Georgia”>

Johnson is clear about his mission. “I always felt the drive to record my people’s hopes, dreams, and struggles. As an African American experiencing racism and discrimination, I felt that I empowered the people I photographed to see themselves more positively–like the man on the skateboard. He could have never afforded a prosthetic, and he’d hit on a perfect way to get around. He must have sensed my admiration and allowed me to take his photograph.”

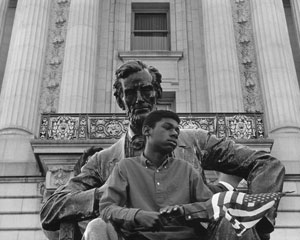

Johnson’s images capture this admiration, a deep empathy for his subjects, and a subtle symbolism. On Lincoln’s stone lap, a boy looks sidelong, as if his physical presence on the icon can help fulfill the promise of equality. Another boy pulls a wagon with a smaller boy in it under a waving American flag, and one can sense the struggle up a perpetual uphill street.

Copyright © David Johnson

Boy with Lincoln statue

Copyright © David Johnson

Boy pulling wagon

Copyright © David Johnson

An elegant African American lady looks oddly unpretentious even in her finery.

Johnson’s photographic career spans over 60 years, and he has broken through many racial and age barriers in other areas as well. He was the first African American to run for San Francisco County Sheriff, and he was a university personnel administrator and a civil rights activist. At age 71, he received his master’s degree in social work from an Eastern university and practiced for several years with underserved populations. In his 70s also, Johnson realized another long- held ambition. He took acting classes and appeared in 35 television commercials and several first-run films. And on his recent 83rd birthday, he got married.

Copyright © David Johnson

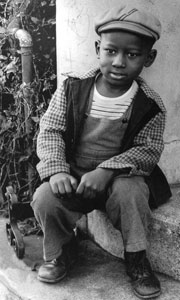

The sweet and mischievous Clarence (Johnson’s signature photograph) is apparently untouched by society’s injustices.<style=”font-size: 10.0pt; font-family: Georgia”>

<style=”font-size: 10.0pt; font-family: Georgia”>

Johnson has no intention of slowing down. “As we progress in the twenty-first century, I will continue to document the lives of African Americans.” He continues working with community groups to document and preserve the Fillmore District’s rich history. In late 2008, a large retrospective show of forty of his works opened at CaliforniaStateUniversity, Chico. In June 2009, Johnson had an exhibit of his works at the Togonon Gallery in San Francisco, which represents him. Current projects include several shows at universities in California and others in conjunction with Black History Month in February 2010. A DVD is in production entitled “David Johnson: His Life and Work in Photography.”

Reflecting on his mission and role, Johnson likens himself to a West African “griot,’” a tribal elder entrusted with transmission of the tribe’s history and wisdom. “By documenting past eras, I am giving people a glimpse of what life was like, maybe for some reawakening painful and proud memories. My work teaches through visual images. They reflect what I have experienced and continue to observe and become a legacy for present and future generations.”

David Johnson has not only broken through racial barriers but also the “calendar ceiling.” He proves that expansion of learning, enhancement of craft, and the drive to create and contribute know no age boundaries. He clearly articulates his legacy of the African American experience. But he may not have envisioned his additional legacy—as an inspiration to artists of every race, age, and genre.

by Noelle Sterne

Leave a Reply