When I began to photograph, I thought a good portrait was the result of technical knowledge, intuition and luck, and if the gods of silver gelatin were smiling down on you, they all came together at the moment you released the shutter.

But I was puzzled–how did one reveal the sitter’s personality, or even recognize it? I acquired technique, but the essence of a person wasn’t as clear cut as f16 at 250. And so I waited patiently for that fleeting, meaningful expression, and so often it eluded me.

I was fortunate to learn the reason why and began to ask the kind of questions every photographer should consider:Am I really interested in knowing another person deeply? Do I think their thoughts and feelings can add to me, make me more of an individual?

As I hope to elicit an emotion in my subject, do I hope to have a large emotion myself? My answers, at the time, unfortunately ranged from maybe to no. For example, when I had a conversation with someone, I often only half-listened when they spoke, as I was thinking about something more important–what I had to say.

This conceit didn’t change just because I put on my “photographer’s hat.” While I was usually more attentive looking at someone through the viewfinder, I was photographing under a handicap, because if you aren’t sure the depths of people are worth exploring, they’re not likely to show them to you; and if they do, that significant moment can easily pass you by unnoticed!

During an consultation many years ago, I began to learn that, like every person, I had an attitude to the whole world that showed in the way I saw people.I was asked: “If you have to give your attention to something else, as a photographer, what does it take your attention away from for a while?”I answered, “From myself.”

From that I learned that giving all of my thoughts to someone else for whatever the length of time I am photographing means the ‘self’ is not given a thought, and at the same time, it takes care of the ‘self’.

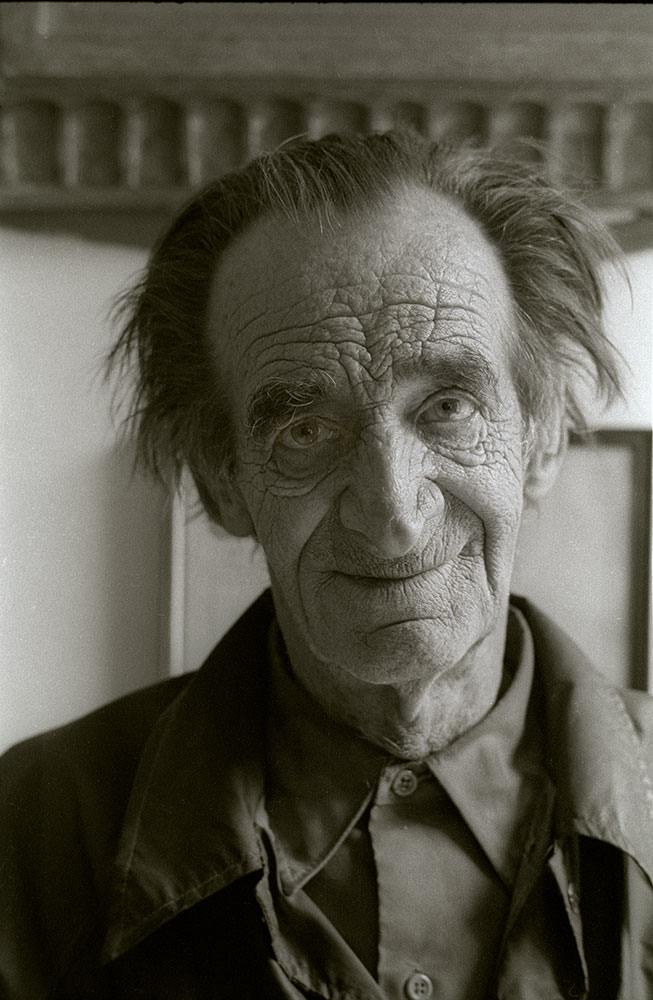

Portrait of Harriet

In the process I learned that I could express myself through being fair to what is not myself, and this is what I was deeply hoping for as a photographer and simply as a human being. In the days and weeks that followed, people and things took on new meaning for me. I was more excited than ever about photography, and began to have proud emotions.

In the Portrait of Harriet, the symmetrical composition and the even distribution of light and dark upon her features makes for serenity. But even as a woman sits reposefully, I learned, there is the motion of thought and feeling within her that takes in all of reality.

It is in her expression–thoughtful, keen, and friendly. The lively, dark strands emerging from her bound hair are important; just imagine the photograph without them–see how it gets too placid? I think they comment on, give outward form to, the dynamic self within.

The criterion for any successful work of art and why it moves us, was given by the American philosopher, Eli Siegel, when he stated: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

Surface and depth are opposites crucial to any portrait: the camera shows the surface of things, and a good photographer uses surface to be fair to an individual’s depths. This desire to be just makes for beauty, and it has only one enemy: contempt – that lessening the value of people and things makes us more important.

How often do you go down the street making fun of how people look, hoping to find flaws in them! When you look through the camera, you can’t just turn that off.

I was learning how the slightest twinge of superiority in a photographer cripples their ability to be fair to the subject. It is also responsible for the ordinary pain of domestic life, and the worst aspects of humanity.How much suffering has come from using surface appearance–the way a person looks or dresses, the color of their skin—to dismiss their thoughts and feelings and act superior?

Beauty itself arises from the kind, exact way of seeing people we need to have every moment, for the man or woman we stand next to in a subway car, or the person who waits on us in a restaurant, let alone a loved one sitting across from us at the breakfast table.

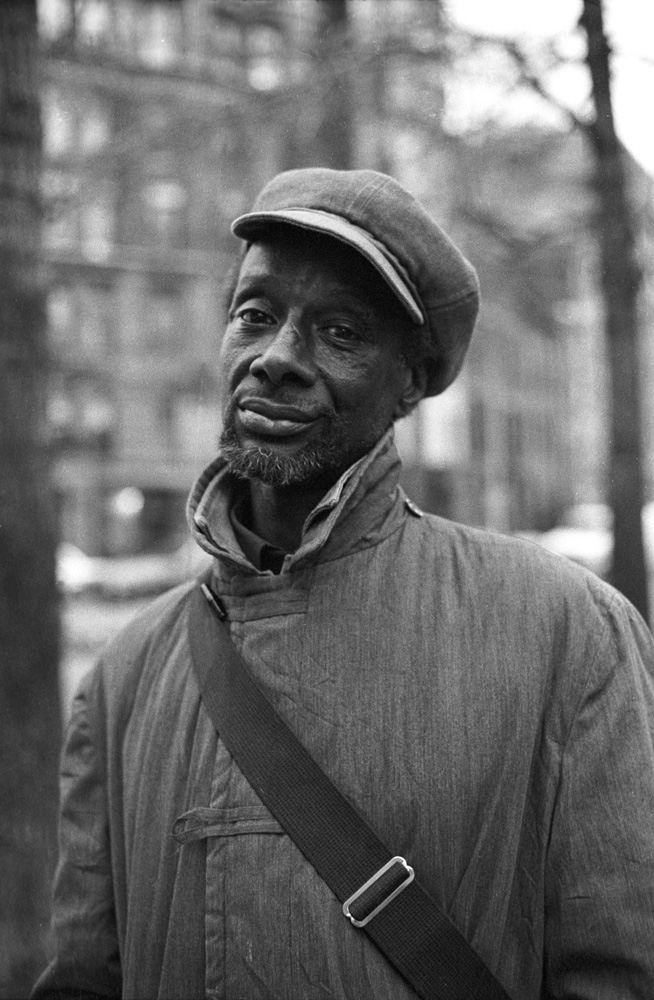

Korean War Veteran

When I saw this man on the street I felt he had stature, dignity and felt impelled to introduce myself and ask to photograph him. When he told me he had fought and been wounded in the Korean War, I felt at a loss and simply said that I had no idea what it must have felt like to be a black man in America in 1950 going off to fight in the Korean War.

His expression is a mingling of bitter weariness and yearning. There is an energetic line that sweeps upward through the diagonal strap across his chest, around the curve of his collar and tilted head and cap, leading our eye toward the brightest area of the photograph–a corner of sky in the upper right.

This effect counters the feeling of sadness and intensifies it.

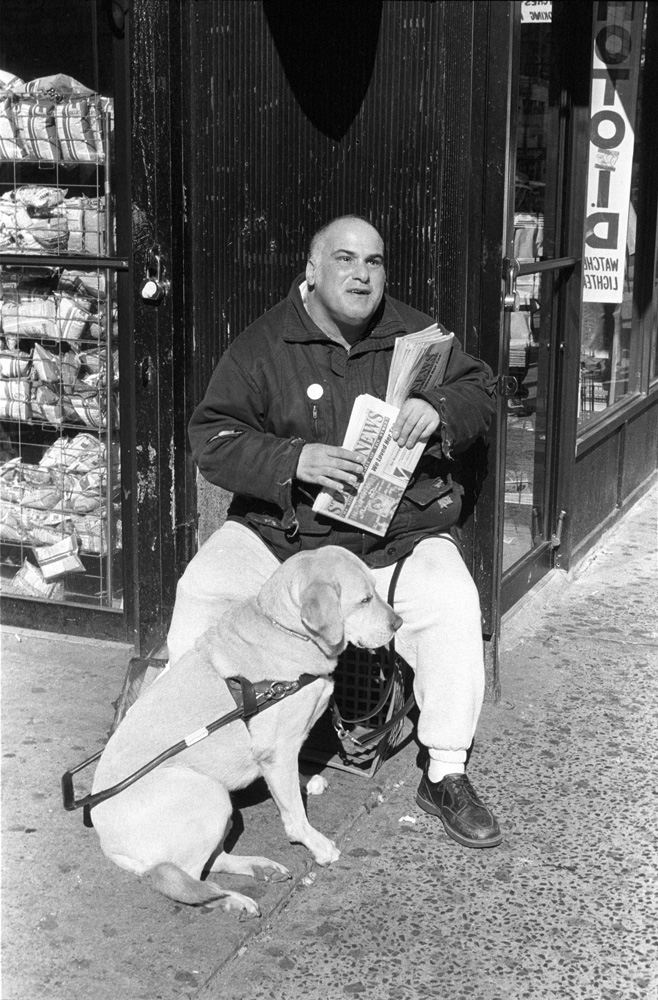

Man And Seeing Eye Dog

A question that can help us see a person’s depths, is one which Eli Siegel said a photographer could ask before taking his or her portrait, “What quality would you like to represent you in a photograph?” And that is just what I asked this man who affected me very much as he spoke about how difficult it was to earn a living, and that he wanted people to see he was proud of doing honest work.

In this picture I think his upward gaze has that quality of pride and, while he himself is blind, he seems to be looking at something quite beautiful. The seeing-eye dog, faithful and enduring, is contained within the outline of his form and this heightens the feeling they are so much of each other’s lives.

Young Woman Holding Cat

I have learned that men and women have essentially the same questions, trying to put the same opposites together in our own unique way.In this photograph [Young Woman Holding Cat] we see a young woman whose expression is thoughtful and penetrating; welcoming, with a touch of suspicion.

Does this sound like anyone you know?(everyone, ladies and gentlemen alike, should be raising their hands at this point!) And even the pussycat is gentle and sharp as it vigorously nibbles the hand cradling it.

Boy in Classroom

Like others, I often felt my individuality depended on separating myself, and I think this photograph [BOY IN CLASSROOM] criticizes that feeling. The child stands out sharply against a vague, complex background.

Yet, he is nestled by his surroundings: a white flower curves toward him on the right, and the bright geometry of counter-tops touches him at various points. His expression is strong and trusting, and he does not seem at odds with his environment, which includes books and people–rather, his relation to it makes for a sense of largeness, emphasizes what we see as the boy’s strength of character.

When I read these magnificently kind sentences by Eli Siegel my heart and my perception were stirred, and I knew I would never see people in the same way again. They are from one of a series of lectures he gave in 1951 on H.G. Wells’ The Outline of History:

[T]he very great technician, Nature, while working in a space of not more than twenty-five inches or so–that is, the human face–has come to have so many faces, feminine and masculine, child and adult. They are all different.

We can assume that every Paleolithic face was different, also Neolithic, also Roman face, Chinese face, Greek face, Mesopotamian face; and just how it’s done is remarkable. Any person trying to imagine five hundred faces will find it very hard, but somehow Nature has been able to have a tremendous variety, an inconceivable variety, in that field–which has to do with the relation of variety and oneness.

The implications of this beautiful description are far reaching. Where the difference of others has been used to wipe out our common humanity, here it makes for soaring wonder and respect. This way of seeing can only make for self-respect. And, as a photographer, I know it also makes for endless picture possibilities and the unique vision we hope to convey in our work.

Assignment: Find out how your subject hopes to be seen . . .

First, ask yourself, with or without your camera, “How much time during the course of a day do I spend thinking about myself, and how much time do I spend thinking about other people?”If you’re anything like I was, you spend more time on your own thoughts than on others’ (and when we do think of someone else, it’s usually in relation to us!)

Second, the next time you take someone’s portrait, ask them the kind question suggested by Eli Siegel: “What quality would you like to represent you in a photograph?”Three things will happen, if you ask with sincerity:

1) You’ll have a good effect on another person,

2) The privilege of trying to understand how another person hopes to be seen will be yours

3) You may make a photograph that is fair to the person and you can be proud of forever.

Aesthetic Realism is the scientific, kind study of art and ethics, based on these three principles stated by Eli Siegel:

One – Man’s greatest, deepest desire is to like the world honestly. Two – The one way to like the world honestly, not as a conquest of one’s own, is to see the world as the aesthetic oneness of opposites.Three – The greatest danger or temptation of man is to get a false importance or glory from the lessening of things not himself; which lessening is Contempt.

Leave a Reply