My father had a blue Opel car and, even though two others that looked the same drove about in the neighborhood where I grew up, I could recognize his from far away–even without reading the plate. I was reminded of that odd fact several years later when I recognized my daughter’s moped among many like hers standing in front of her school…..

Her moped didn’t have any scratches or original stick-ons–no identifying mark that could have guided me. I just knew which one it was. I stood in front of the moped wondering whether things communicate who they are rather than what they are and whether another parent would have had the same perception of his daughter’s moped.

It was as if a feeling had developed between the object and its owner, a feeling that could be perceived by the one who shared something with the owner.

Did I recognize my father’s Opel car just because he was my father? Did I recognize my daughter’s moped because she is my daughter? And if this happens, indeed, does the object acquire an illusory personality thanks to a sort of emotional transfer that turns into a message?

I did perceive that very message, though without knowing how.

I am a photographer, and I realized I might photograph that emotional transfer. I might photograph the message the material sent rather than merely the material itself. I started looking around in a completely different way, using a new awareness, trying to pass through the inanimate.

What increased my fantasy more than anything else was the image of washing drying on a line. I thought about the way in which it was arranged. I could figure out a family’s life by reading it. My fantasy listened to the clothes and pants; they told about the personality of the one who had hung them out in the sun, of his habits, of his relationships, of his shyness, ostentation, reluctance…. I have even photographed clothes and pants trying to render these perceptions.

Step by step, I realized I was not photographing material at all; I was actually shooting what I could see in it. Nevertheless, I was still unable to find a kind of fil rouge to link up all those attempts. I was photographing my fantasy; I was not releasing what was in front of my eyes.

I was trying to listen to “the message” coming out of all that I was looking at. This inevitably brought me to feel muddled and rather disorganized while making a choice.

Historically speaking, photography has usually been employed as a means to document reality as well as to emphasize it, following a constructive process that maintains that the element to be reproduced lies in the material, a constructive process that keeps the conceptual originality.

The use of the camera has enabled the photographer to overcome the technical hindrances of painting. However, the different constructive process of painting has changed the photographer’s conceptual approach together with his interpreting skills.

Painting means touching by the hands as well as by the eyes; it means to feel the image forming under the strokes. The thing is not yet completed; it gradually comes out after a process that first of all belongs to the mind.

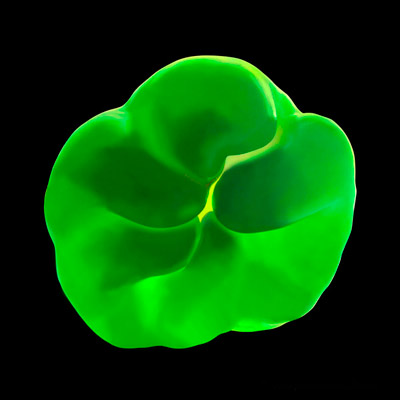

Photo of pepper titled “Comfortable” by Piero Leonard

I was actually searching for a key to help me perceive what I have always thought to be the painter’s emotion when he paints his work. Why can’t the photographer undergo the same creative process? Is it so perhaps because the camera keeps the photographer away from the subject, whereas paintbrushes allow the artist to create it by touching it?

Or is it the mind that gives life to it through the paintbrush? Does the time taken to accomplish the work help the artist as well as the photographer with the process?

While I was trying to focus my reflections, I approached Duchamp’s work, his “ready-made”, the deep sharing with Man Ray and the process the French painter underwent for Conceptual Art. I was fascinated by the raising of common objects to works of art.

They were dégagés from sentimentalism as well as from bonds of affection. And it was thanks to “ready-made” that I realized my father’s Opel car or my daughter’s moped were objects tied up by strong bonds of affection which I shared. The clothes and pants hanging out in the sun were tied up by the same strong bonds, since they belonged to someone.

I gradually started rearranging my research, which I did not consider as such yet. I kept on examining the world through an interpretative glance, trying to overcome the visual impact of superficial looking to reach a more hidden essence.

I tried to shoot the passing of time on the bark of the trees, to click the rest in a heap of worn tires, to release the cool in ripples or in the shade of an oak-tree. All and each I saw was leaving its material aspect, turning into the vehicle of that very sensation.

“Pepperlife” has been the first factual result of my newborn visual approach. It came to life by chance. I was buying peppers in a supermarket. Fruit and vegetable racks have always attracted my curiosity–loads of different, colorful forms that, after having grown up distant from one another in the open air, now definitely lay together, often one on top of the other.

I remember I was holding a pepper in my hand and while I was swirling it in the light, I saw a woman’s body through it. Then I started finding other ones that could prove to me they were not merely peppers. The neon lights in the store were no longer that which revealed them; it was my emotional light that did so.

While I was observing them, Duchamp’s conceptual approach to his art came to mind again–no more bonds, no more choices in the process, because any instrument would have produced the result.

Peppers were just this–common objects that anyone might have seized; they didn’t belong to anybody. Suddenly my perception towards them changed again. I didn’t just scan their shapes; I didn’t sense their likenesses anymore.

Now I saw them as if they were sleeping bodies searching for somebody who, among all the indifferent clients searching for other things to buy, would finally pay attention to them. I picked up the ones that seemed to call to me. There again a message came from apparently lifeless objects.

This time no affective transfer was working. My physical approach changed, too. I grasped them, turned them upside-down and scanned them more carefully. I realized that in order to strengthen my perception of their personalities, I was actually trying to identify myself with a pepper.

I kept on scavenging in the heap, searching for “my artistic objects-subjects,” trying to see beyond the shapes as well as the colors, trying to listen to their personalities. The message turned out to be unequivocally clear.

On the way back to my studio from the supermarket, I thought about the relationship between Photography and Painting, about the time the two artistic expressions take to create the image, and I had half a feeling that my photo had started being shot in the supermarket. I had started forming the image far away from the studio and from my equipment, as well. Was I following the painter’s time process then?

“The Scream”

“Dancers”

The observation went on in the studio. I placed a light and came back to scan the peppers. I passed through them using my imagination. I sectioned them and touched them with both my hand and my mind. I arranged them side-by-side and one in front of the other, trying to listen to the message they were exchanging.

The images slowly came to life in my mind. They were helped by what my fantasy was listening to, by what my fingers did touch, by their soft and winding, sensual and colorful, shapes. There my own process started to transfigure reality.

“Life”

“Dancer Ghost”

The use of the camera was just the epilogue. Suddenly, that expensive device rich in technology had lost all its technical value, simply turning into a vehicle capable of describing my imagination. Time as well as visual scans have been the paintbrushes that have accomplished the picture.

by Piero Leonardi

Article: © 2011 Piero Leonardi. All right reserved.

All photos: © 2003 Piero Leonardi. All right reserved.

Leave a Reply