The pictures on our walls are a gallery of our thoughts. How we think is the foundation of our photography. My goal here, is to highlight a few contradictory ideas and their language, so we might be open to more flexible thinking in our photography.

CONTRADICTIONS

I saw a street performer this week who, dressed up like a short Marcel Marceau, squeezed his entire body through the open, unstrung head of a tennis racket and called himself the world’s only talking mime. A talking mine? Thinking over his description made me wonder about contradictions.

There are many contradictions in photography: The more I know about photography, the less I know. Reality is only appearance, comprised of what we pay attention to. For someone taking pictures while travelling at the speed of light, there is no such thing as time. A photographic idea, and its opposite, can both be true.

There are also contradictions within a single photograph. A photograph may a) be both sharp and blurry and b) show a moment in time that no longer exists and can capture and freeze the death of that moment. The key is understanding that contradictions are not lies. What causes these contradictions? While our brains search for patterns and meaning, at times these can not be reconciled into neat categories.

Physicists, for example, talk about light in probabilities: light is neither a particle nor a wave, but shows wave properties, and particle properties, depending on how you measure it. The key is understanding that these contradictions are not lies, they are a function of our brain.

Also, two contradictory ideas do not have to be true at the same time. An idea may evolve over time, and gradually balance out what at first seemed like an irreconcilable contraction. The idea of a smaller camera for quality images, for instance, did not catch on when Thomas Edison introduced a portable film camera in 1896, but after Leica tackled the problem, small cameras became the norm with the passage of time.

COUNTRY OF THE BRAIN

Our brain is not a computer. When we describe brain functions as default, reboot or left and right brained, we are using generalizations from machine learning, and thus missing most of what our brain is doing. Instead, let’s think of our brain’s structure as a huge, ever-changing country with an enormous population.

Metaphorically, the people in the country are the brain cells, or neurons. We think their population numbers about 86 billion, the number of neurons in the brain, but this is a WAG (wild ass guess). In this country of the brain, there are towns, villages, regions and self-governing states.

It is not the number, but the relationships among these regions that is most important. It is the person- to- person connections that truly count.

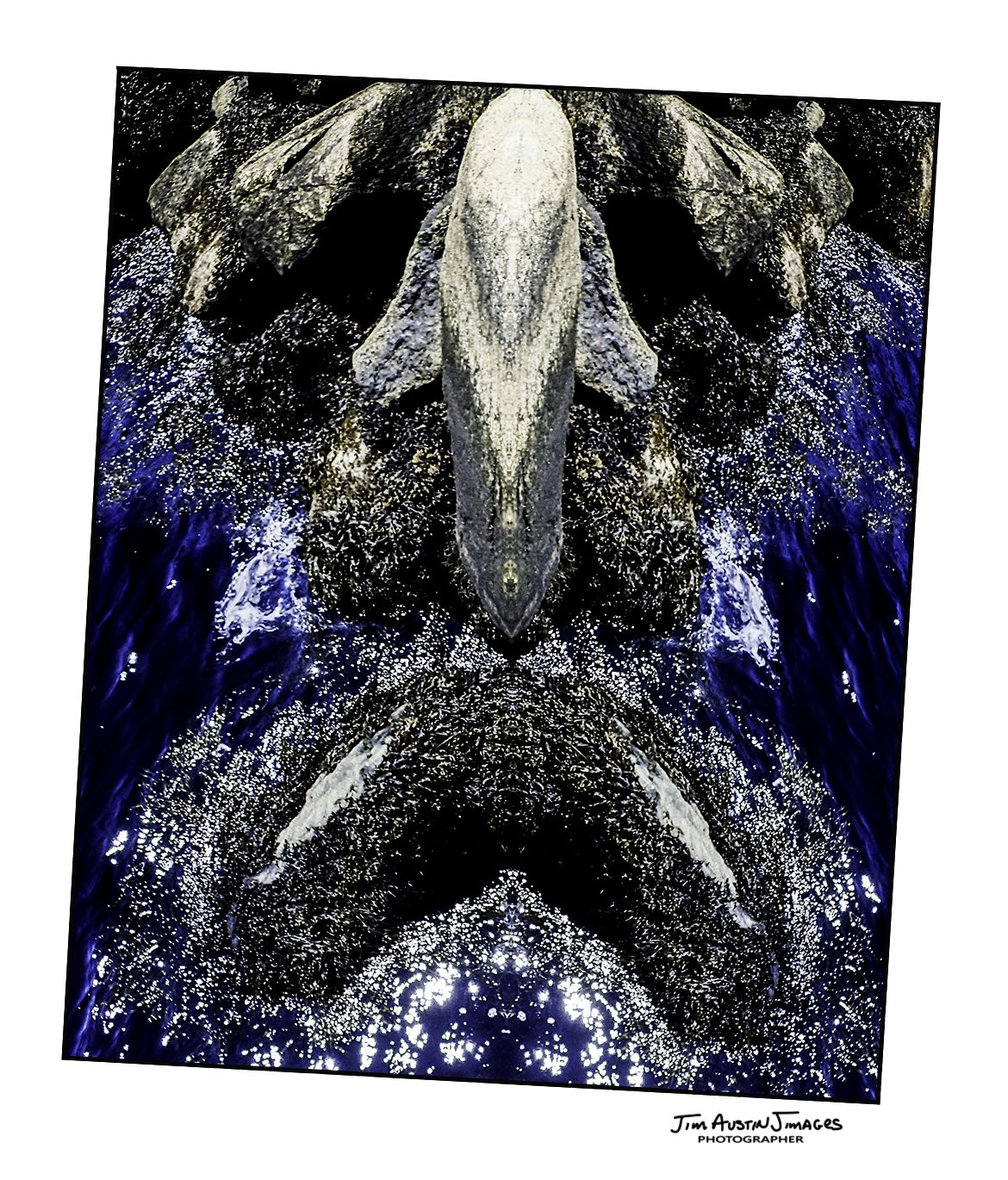

Above: Photograph of shore-side rock and kelp, expanded in Photoshop into an abstract human face.

THE SEARCH FOR BEAUTY

So, at one level, we have brain cells. They bundle together. The cells are organized into regions. These regions form lobes, and the lobes form hemispheres. Using the country metaphor, the land of our brain is not uniform, some parts are much more tightly packed than others. Our left hemisphere both inhibits and excites the right hemisphere. The right excites the left hemisphere, and suppresses it. Our consciousness, and our awareness as we search out photographs, is a dynamic collection of sensations, perceptions and memories.

We know very little about our brains, and metaphors fall short, because the map is not the terrain. There is not much resemblance between the reality of our brain and our current models of how we think it works. What does this have to do with photography?

It is misleading to talk about right brain and left brain in photography. We rarely speak of the ocean as the “right” or “left” ocean. We call one area Atlantic and one Pacific in our speech, but these are generalizations. The oceans is one, a whole much greater than the parts.

The huge country of the brain is not some mass of brain cells, because the structure of the cells matters a great deal. Function follows form; we do not take a picture with a random hunk of glass, metal and plastic, we take a photo with a camera. We need a useful framework that incorporates these details of sensations, includes our emotions, and gives us a firm sense of meaning.

SEARCH OUT OPPOSITES

My goal here is to highlight contradictory ideas and their language so we might teach ourselves how to think differently. Just as we learn language, we can consciously search for contradictions that invite novel imagery. Our brain is the basis for our attitude. It has, at times, only imprecise, contradictory language to communicate, so we can use the verbal ideas to train our vision. Creative images might arise from training our brain, though its thoughts, to learn new visual language.

We can do this by searching out emotional experiences and, over time, framing them with meaning.

There are no shortcuts in photography. Learning to search out things that are the opposite of what we expect takes will and a curious and open attitude. Because there is an irreducible complexity inherent in photography, at times our images will capture contradictions that can not be resolved. When we search for the opposite of what we expect, we often touch upon the mysterious.

NO THINKING DURING THE SHOT

A photographic idea is not fixed. Like time itself, ideas are relative. Expanding our idea of space-time does wonders for how we see, despite what Henri Cartier-Bresson believed: “And no thinking. Ideas are very dangerous. You must think all the time, but when you photograph you are not trying to prove a point or demonstrate something.”

In the years since Bresson’s work, his imagery has been widely used to create and support the belief system of the “decisive moment” in photography. The flip side is that all moments are decisive, and many of us do try to prove a point, create a project, or demonstrate an idea with our photography. Could the contradiction behind a “decisive moment” be a trick to make us think about space and time in a fresh way?

A common habit we photographers share is to stick to our story or our project. We deny things outside our project when we’d feel things more deeply if we actively seek them out. It’s cozy to stay with what is familiar, our own personal photo project.

That’s what makes Google and our online world so comfortable. Web tracking Cookies feed us the sugar of the familiar, They prompt us to read stuff that fits our existing models of the world that we, incorrectly, believe to resemble reality. It is warmer in our cave by the fire. We want to tell stories there and stick to our narrative. For instance, a photographer might only look for what is beautiful, or what we see so we can record it.

DISCOVER, EXPERIENCE, QUESTION.

Think of questions and answers and let them be about the future, the present and the past. Be playful. Find the unfamiliar and the contradictory. Try to live outside your own bubble and contradict your narrative story.

By “narrative story,” I mean that we tend to see what we are prepared to see. On a photo walk, for instance, if I have a tightly constrained visual sense of what is going on, I miss most of what is actually going on. My frame, beliefs, visual skills and attention put boundaries around what I am able to perceive. My emotions take hold. If I see a poisonous snake in the water in the morning, I am going to be watching out all day for snakes, and perhaps not swim in the water that day.

Not a bright idea for someone trained to observe. Later, when I find out the snake I saw was not a water moccasin but a harmless brown water snake, i feel foolish. So, Henri Cartier Bresson’s point about ideas is relevant, because we can teach ourselves to photograph the opposite of what we believe, to help rattle our preconceived beliefs that limiting how and what we see.

No matter how much you believe something to be true, keep asking questions in your photography like “Is the opposite also valid?” and “If I pretend the opposite is true, what happens?” There are many ways to photograph, and they can begin with how we think. The reward of practicing this is that I free up abundant energy to create, especially when I look for contradictions.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jim Austin is a photography educator, workshop leader, and Apogee Magazine’s Photo Coach. He is the author of Ruins and Rust, and a founder of the Slow Photography Movement. Find him at Jimages.com and on Facebook.

Leave a Reply