This is a story about swans. In particular, it is a chronicle about a pair of mute swans. Its moral? The blessing of photography is the process, not the picture itself.

In Rhode Island, there is a large pond known as Point Judith Pond that covers about 500 acres. Overhead, clouds that look like angels float southward toward Narragansett Bay. Local fishermen rake quahog clams up out of the Jell-O thick, black bottom mud at low tide and sell them for a quarter apiece. Riding the water, at high tide, white swans mate and raise their young in between the wakes of fishing boats from the towns of Galilee and Jerusalem.

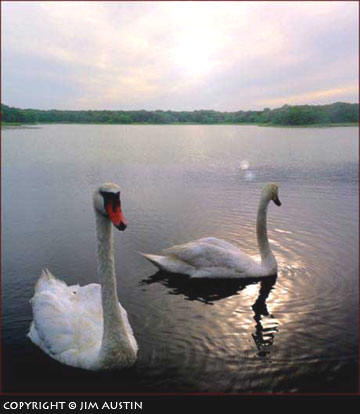

Sailing to Rhode Island in June 2002, we anchored a catamaran on Point Judith Pond. The boat, at rest a couple hundred yards from shore, provided a stable platform from which to take eye-level pictures of the swans. When two mute swans came by, I made Photo 1 (left). This picture represents two digital frames combined. I photographed the swans, and, a moment later, I shot the green tree line and sky and added them to the image using Adobe Photoshop. Then, I added a lighting effect. In June 2004, two years after Photo 1 was made, I took a second trip to the pond and found myself looking at another two mute swans that approached the boat at anchor.

On this second rendezvous, the swan parents brought five cygnets, or baby swans, (pictured below-right) with them. These little ones kept up a lively peeping call, not living up to their name as mute swans.

Perhaps the same adult swans we’d seen in 2002 had mated in the intervening two years. In any case, their reappearance was encouraging and suggested an unbroken circle. Maybe time and tide do wait for swans.

When seven swans paddled cautiously over to the boat, I made Photo 2 (at lower right). Something was not right with the picture. To put it plainly, it lacked contrast and was ho-hum. There were no pure whites. Also, the color difference between the babies and adults was not clear because the light was so flat. Happily, the next morning the family swam by again while the sun was cloudy-bright. What brought them back? Perhaps the white fiberglass boat looked like a giant swan. Their return seemed mysterious.

Unbeknownst to the swan family, they became a center of attention, and Photo 3 (below left) happened on their next visit. That morning, the sun was out and the pictures had good contrast. So far, every encounter differed from the previous one: the swans approached from a different direction, the overhead lighting changed, and the water conditions varied. The variations made each encounter flow by quickly. The swans appeared. They vanished.

I am puzzled when people ask me if I shoot film or digital. This question is like asking a bird if it sings classical or folk music.

Connecting with these birds, I thought that photography is as much about staying with your subject over the years, as is it about any other skill. Shakespeare said, “I am a kind of burr, I shall stick.” Did the swans stick to me, or was I stuck to them? It didn’t matter. What counted was the process took over, and my sense of self faded as the swans’ beauty grew. In the presence of such magnificent birds, I felt humility.

When people ask if I’m religious, I say, “ Yes. I am a devout photographer.” Sharing the rise and fall of tides on Point Judith pond with mute swans, piety seemed to play a role. When you practice photography as you practice breathing, one of its joys is connecting with your subjects without effort, and feeling as if you’re the first to see them, even though others have been down the same path. When you make pictures daily, good pictures emerge, and wild creatures share graceful moments. People become sidetracked about whether the image is digital or film. The essence is not simply about the image. It’s about the integrity of the process–especially if you’re a photographer who cares more for your living subject than for images of it.

Sometimes, unique moments in your image-making happen when you let go of your self. Lasting photographs surface when you stop trying to capture splendid pictures, and let go of being a heroic photographer, when you stop trying to be crazy or brave, and are simply wholly in the present with your subject. Then the attention you give your subject is its own reward, and making images becomes timeless and full of bliss.

The picture at the lower right came after two years, on the fourth day of being with the swans. A baby swan climbed on its mother’s back for a “swanny-back” ride. To see this happen two years after first observing these swans brought me full circle.

The baby swan had a warm, soft ride, nestled in its mother’s unruffled feathers. It saw a huge white neck ahead of a horizon of sky and water. It rode the waves on its mother’s back for a while before swimming off on its own.

We were out in the middle of a serene pond with the swans, far from people, traffic, and noise. Using a digital camera meant that most of the photographs were made consciously as warm-ups, nothing special. They were meant to be exercises and a way to be ready. As the seven swans kept moving continuously, there was only a single frame out of many in which all the birds arranged themselves in front of the 50 mm lens. This frame was received as a blessing.

Blessings seem to come from letting go and waiting. As you grow older as a photographer, and have less time to live, your ability to wait may grow. Said Elizabeth Taylor, a British writer, “It is very strange. . . that the years teach us patience; that the shorter our time, the greater our capacity for waiting.” Photographing swans from several feet away with a wide-angle lens inspired me. I had a two-year wait before I could share the next moments with these superb swans. So, what is the message? It’s okay to wait for photographs. You don’t have to race top-speed after them.

Waiting for the muse in your picture making, you’ll have periods in your life that are productive, and some not so. There are high and low tides to your image making. Some days will feel like the flood tide streaming shoreward and others like ebb tides returning to sea. Be loyal to your photography process, and this devotion will surface in your images.

Oceans have tides, produced by lunar cycles. In digital photography, movements and changes are like the tides. The following are eight current trends, tidal changes in the world of digital imaging:

1. A trend towards smaller, lighter, faster cameras and combination cameras with dual functions similar to those of cell phones.

2. The association of cameras with violence. Digital cameras are used to capture tragedies as they happen, i.e. Princess Diana, the Gulf War, and the Iraqi prison scandal. This trend gives rise to digital war photography with inane metaphors of the camera as a gun. For example, the June 2004 issue of PEI magazine has a quote on the cover, “The brave ones were shooting GUNS. The crazy ones were shooting CAMERAS.” This is a dead metaphor. Its use goes back many years to a time when cameras captured the Civil War.

3. Web sites and TV shows becoming a driving force behind making, storing and exchanging still images.

4. As funding permits, digital photography slowly replacing film-based facilities in academic programs (RIT, NYI, and California).

5. Portable personal computers acting as portable light rooms, replacing the chemical dark room.

6. The growth of a digital thinking paradigm in photography: multiple imaging, time lapse, blended still imagery, multi media photography, digital processes for increasing exposure and depth of field.

7. The dominance of software to the point where a culture springs up around it (i.e. Photoshopping or 3-D).

8. The extension of digital photography to a performance medium (i.e. street performers with computers just like artists with spray cans).

“My poor fellow, why not carry a watch?”

… Herbert Tree, British actor, remark made to a man carrying a grandfather clock.

These movements persist. They even allow for some predictions. First, given the ease of the digital process, more pictures have been taken since digital photography began than in any decade since photography was invented in 1839. However, fewer digital prints are made per frame taken than before, because it’s expensive and time consuming for home users to print digital pictures. Second, film and its disciples will be around for many years. Just because there are steel and fiberglass boats doesn’t mean wooden boats are extinct. There is a special feeling with a wooden boat, and so it is with film.

Many film photographers I know are still carrying cameras that are grandfather clocks. That effort is just fine, because it’s the good times that matter, not the timepiece. It’s about the process. While some are carrying four-ounce digital cameras, others will lug 30 pound 8 x 10 plate cameras. It’s all photography.

Celebrate the practice of your picture making, not just the pictures themselves.

by James Austin

Leave a Reply