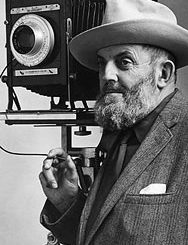

Editors Note: One of America’s most productive and distinctive portrait photographers, Arnold Newman has recorded the history of this century through his photographs. His sitters have included many of the most prominent and influential figures of the post-World War II era. Newman’s portraits are subtly complex. Although at first glance they are easily comprehended, through study, they engage viewers in uncovering his exploration of personality. Considered the innovator of the “environmental portrait,” he photographs subjects in their own environments instead of creating a controlled setting in a studio. Newman has always worked independently, preserving his freedom to react to accidents, respond to his subject’s environment, and solve technical problems. He has been a major influence on the art and practice of photography, particularly on the genre of portraiture, and is still in demand as a workshop teacher in this country and abroad.

They came bearing gladiolas. With the abundant peach-colored bouquet, photographer Arnold Newman and his wife Augusta, guests of honor at a dinner given by artist Mil Lubroth, made the final decorative addition to the oval dining room. A nice touch from the “father of the environmental portrait.”

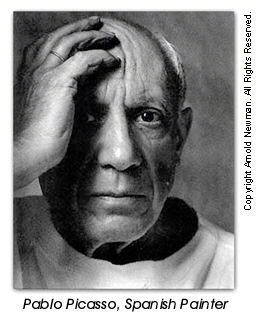

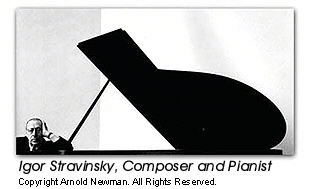

Newman was on the next-to-last day of his stay in Madrid, where his show “50 Years of Arnold Newman,” was one of the highlights of PHotoEspaña 1998. The show was funded by Fundación Barrié de la Maza and included 136 of Newman’s best-known environmental portraits, including those of Capote, Picasso, Mondrian, Stravinsky, and Max Ernst. The photographer delivered his exhibition lecture to a standing-room-only crowd that spilled out of the auditorium and into the street, where his commentary was broadcast on closed-circuit television.

“I felt badly that there was not enough room for everyone,” said Newman. “When I first saw the auditorium, I knew it was not going to be big enough, but I didn’t want to say anything to the organizers.”

Newman is a quiet star, which only adds to his charm and adds bodies to the lines of people wanting his autograph and wanting to know, in one minute and in 25 words or less, if one of “them” should keep working to become like “him”—-a Real (and Famous) Photographer. He both encouraged and advised. “Remember,” he told his audience, “photography is 1% talent and 99% moving furniture.”

It was easy to see why Newman has had such success in that very human art, portrait photography. He is earnest, easy to be around, comfortable to talk to and to listen to, and has a great sense of humor. He maintains all these pleasant qualities without losing his artistic authority—-that ability to say to his subject, “Sit still now or I’ll kill you.” Writer Jesús García Calero called Newman a “warrior-photographer who knows just how to disarm his subjects.”

Newman’s wife, Augusta, whom he met in New York when she was working for Haganah, the underground organization that worked for the establishment of the Israeli nation, is a good match for the artist–calm, poised, intelligent, and with her own brand of philosophical humor. I couldn’t take my eyes off her perfectly round, black-rimmed glasses, a bold visual statement if I ever saw one.

Newman seated himself on a plush couch, the kind that sinks the spine in softness and does not easily relinquish its prey. As the guests arrived, Arnold would look up at everyone, shake hands, smile, and say, “You know, I can’t get up. I just can’t get up.” It didn’t matter. People perched on couch arms, nearby chairs and foot stools, settling in a circle around the photographer-raconteur.

Twelve of us were in the lucky circle:

Natasha Seseña, a ceramics curator and author of numerous books on Spanish ceramics. (The Seseña family make the famous “capes of Spain.” The First Lady and Michael Jackson have been known to sport Seseña capes, among other celebrities.)

Jacinta Nadal, sculptor and dancer, wife of author Rafael Nadal. (Rafael Nadal was the last person to whom Federico García Lorca gave his poetry manuscripts before the poet’s death at the hands of Spain’s Guardia Civil.)

Journalist Gil Carbajal, amateur photographer and English-language reporter for Radio Nacional de España; British writer Gillian Watling; Margareta Schaeder, representative for the Swedish Chamber of Commerce and her husband, exporter-importer Bertram Schaeder; painter Pepe López and his wife Joan Keyser López, an international library consultant; choreographer Felipe Sánchez; and last but not least, hostess and host, artist Mil Lubroth and her son, photographer Adam Lubroth.

Newman has made several trips to Spain and has photographed Tàpies, Franco, Picasso, and Antonio Bienvenida, among other well-known Spaniards. Newman first came to Madrid in the 1950s on assignment for Holiday Magazine. He photographed Picasso in 1954.

“Picasso was too interested in posing,” said Newman. “After the photo session, he invited us to his house, but I don’t think it was because he liked me. I think he was interested in Gus (Augusta’s nickname).”

When it came time to do a portrait of Francisco Franco for Holiday magazine, the Caudillo played hard to get until the last minute.

“We knew our phones were tapped while we were in Spain,” Newman recounted. “In fact, this was the case in many countries I traveled to. The Franco staff kept postponing the photo session we scheduled. They always created some excuse. This went on until we got to the point where we were running out of time, and I was determined to get the photo done and still meet our publishing deadlines.

“Deadlines meant little to Franco’s people, because it was common to hold presses for changes and censorship authorized by the Caudillo. So, when I told them I had to get the photo done of Franco on deadline, they never took me seriously. I really believe they thought Holiday Magazine would wait on them. I decided to go for the phone.

“On a Friday, I called my editor and I told him, ‘Listen, I can’t spend more time here. I am going to leave next Tuesday. I’m sorry I don’t have a portrait of Franco, but it simply isn’t possible to get it done.’”

The editor, who also knew the phones were tapped, expressed his regrets, but agreed that Newman could not spend any more time in Spain. In a few hours, Franco’s office called Newman. On Monday he shot the photo. Newman was the first photographer to ever take a portrait of the Generalísimo in civilian clothes. Franco granted the photographer this one victory, but denied Newman a portrait he wanted even more, that of the young Prince Juan Carlos and Princess Sofía. Everything was arranged, when Franco canceled the shoot at the last minute without explanation.

Both Franco and Picasso were exceptions for Newman. More often than not, once the intense photo sessions are over, Newman and his subjects become friends. This was the case with Spanish artist Tàpies, with whom Newman has stayed in touch and with whom he has traded photographs for works of the artist. These friendships have arisen because Arnold Newman knows how to relate to his subjects with honesty, normalcy, and no small amount of understanding. “The heart and mind take the picture,” he said, “not the camera.”

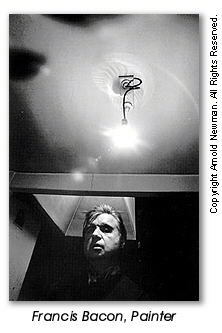

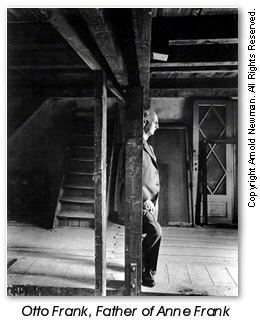

When Newman photographed Otto Frank, father of Anne Frank, he found his heart and mind hesitating. “How could I ask this man to pose?” he shared with us. “I couldn’t. Instead, I just waited, and Otto went into a deeply pensive mood. It was then that I took the photograph.” When the session was over, the two men embraced–and cried.

Through the course of the evening, we learned more about Newman. He enjoys doing abstract photography as well as portrait work. We learned he has a wonderful sense of humor born not only of wit but also of the depth of his personality and experience.

And we learned Newman takes snapshots. He pulled his little Canon from his coat pocket, and like sheep, we amateurs hauled out our little pocket replicas. I thought maybe, just maybe, the Master would give us a little free advice. He did. Newman handed his pocket camera to Gil Carbajal to take a photo. Carbajal focused and pointed the snapshot machine. Nothing happened.

Then the Master spoke. “You have to hold the button down,” he said.

by Ysabel de la Rosa

Leave a Reply