“See what is really there,” Dorothea always said. “Look at it. Look at it.”

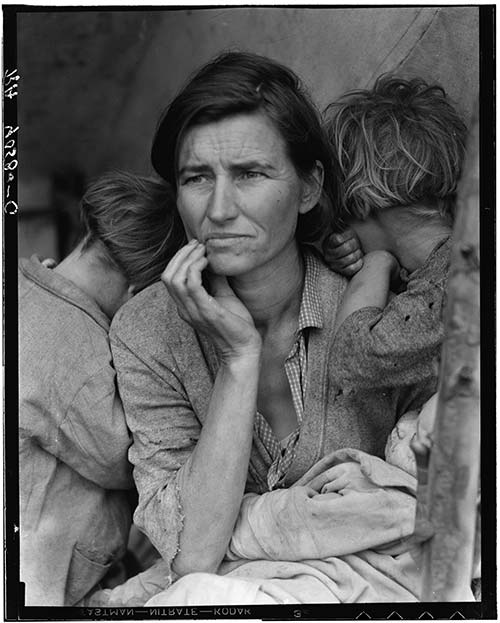

“Migrant Mother”

The Library of Congress caption reads: “Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age thirty-two. Nipomo, California.” Pictured: Florence Owens Thompson with three of her children. Photo Credit: Dorothea Lange, 1936

Her celebrated photograph “Migrant Mother” is one of the most recognized and arresting images in the world, a haunting portrait that came to represent the suffering of America’s Great Depression. Yet few know the story, struggles and profound body of work of the woman behind the camera: Dorothea Lange (May 26, 1895 – Oct. 11, 1965).

Dorothea Lange’s career spanned five decades. In 1919, at the age of 23, she daringly opened a portrait studio in San Francisco. Meeting her husband Maynard Dixon, 20 years her senior, exposed her to the bohemian art world and the wild southwest, where she photographed in Hopi country.

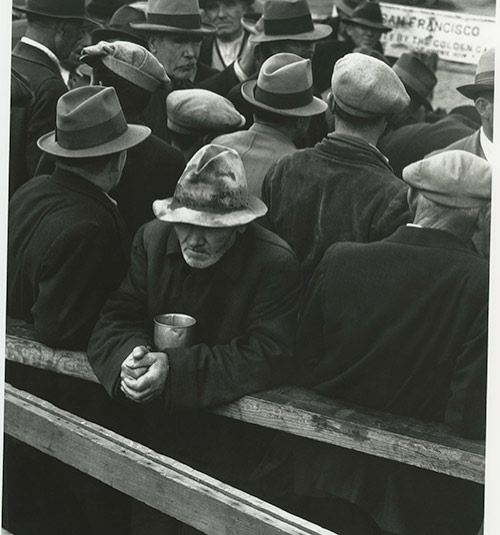

“White Angel Breadline,” San Francisco, California, 1933, as seen in “American Masters – Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning.” Photo Credit: Dorothea Lange, 1933

After living in Taos, N.M., with Maynard, their two sons and step-daughter, Constance, they returned to San Francisco at the height of the Depression. Stresses on their marriage and livelihood led to their divorce. With the advent of the Great Depression, Lange felt compelled to take her camera out on the streets of San Francisco. The resulting photographs lead to work with the Farm Security Administration as a documentary photographer.

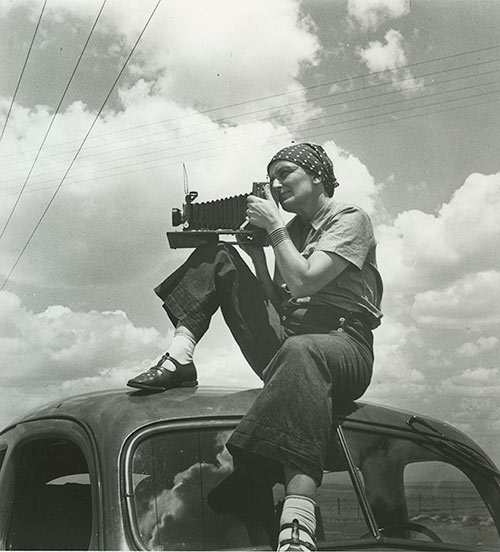

In 1935, Lange married Paul Schuster Taylor, an economics professor at the University of California, with whom she worked in the field. Taylor and Lange lived, loved and worked together in intense collaboration until her death in 1965.

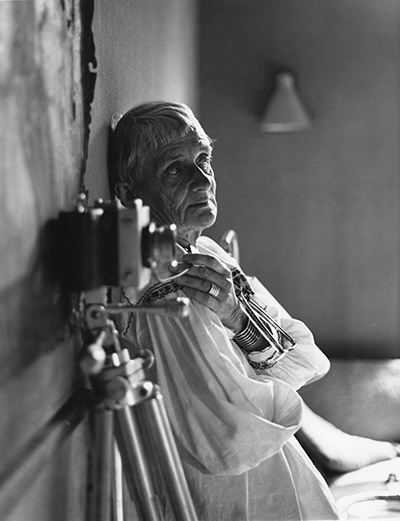

Dorothea Lange, 1937, as seen in “American Masters – Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning.” Photo Credit: Paul S. Taylor, 1936

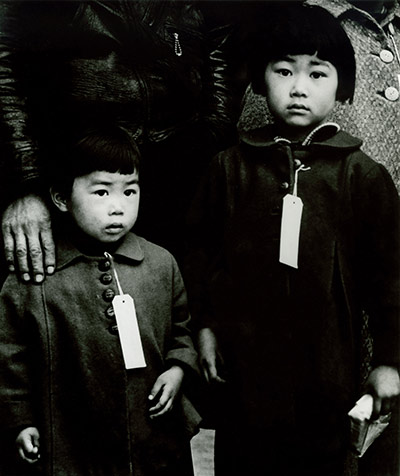

During WWII, Lange photographed the horrible dislocation and internment of Japanese Americans. An early environmentalist, she photographed in the 1950s what she called “The New California” — the massive changes and pressures on the Golden State.

Her increasingly poor health led to short bursts of work doing photo-essays for Life and Aperture magazines. On world trips to Asia, South America and Egypt in the late 1950s and early 1960s, she created an extensive, lyrical body of work.

“Enforcement of Executive Order 9066. Japanese Children Made to Wear Identification Tags,” Hayward, California, 1942, as seen in “American Masters – Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning.” Photo Credit: Dorothea Lange, 1942

Lange’s final years were astonishingly productive. She continued her photography on American women and on her theme “Home is Where.” Her journal reflected her personal debate over whether she was a craftsman or an artist and whether her efforts to document the human condition should be considered “art.”

Her ultimate effort came when she was dying of an inoperable cancer of the esophagus, in reviewing her life’s work, preparing a retrospective exhibit for New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Her one-woman show would be only the sixth dedicated to a photographer and the first for a woman photographer.

Dying Damera – Dorothea Lange in her Bay Area home studio, 1964, as seen in “American Masters – Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning.” Photo Credit: ©1964, 2014 Rondal Partridge Archives

Despite her painstaking work in selecting images for the exhibit, Lange would not live to see the finished result. She died on October 11, 1965, at age 70, shortly before the MoMA retrospective opened to widespread acclaim.

Director’s Statement by Dyanna Taylor

Taylor, who learned to see the visual world through her grandmother’s eyes, combines family memories and journals with never-before-seen photos and film footage to bring Lange’s story into sharp focus. The result is a personal documentary of the artist whose empathy for people on the margins of society challenged America to know itself.

Dorothea Lange was my grandmother. She was brilliant, charismatic, complex and her still camera was her muse. Growing up surrounded by her still photographs, which were everywhere — in stacks, in drawers, tacked up in her workroom — left an indelible impression on me, both personally and artistically. Ever since I began my career in filmmaking, I’ve wanted to make a film which would express the true breadth of her work and the ways she perceived the world.

“American Masters – Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning” filmmaker and narrator Dyanna Taylor (left) with her grandmother Dorothea Lange, 1963. Photo Credit: Paul S. Taylor

Over the years, as we spent time together, she taught me how to see — to understand that nothing is as it appears at first glance. When I was 10 years old in California, I collected a few rocks and shells in my hand and thrust them toward her, probably seeking her approval. Boasting, I said: “Look Grandma, look at these!” I did not get the response I’d hoped for. She looked at me with her deep, commanding gaze and said sternly: “Yes, I see them, but do YOU see them?” And she snapped a photo of the shells in my outstretched palm. I felt dismissed, but also challenged. From that moment on, my grandmother’s words in my mind, I perceived the world differently. To this day, along with everything I learned from her about composition and framing, I carry a sense of the truths found beneath the surface of things, as much an approach to art as a philosophy of life.

Most people know Dorothea from her penetrating Depression-era photos such as “Migrant Mother,” images that portrayed the anguish of the times and shaped the way America came to know itself. But beyond those familiar photos, Dorothea’s body of work, which spanned five decades, is equally powerful and compelling. She often said, “A photographer’s negatives become his biography.”

Dorothea Lange’s First Photo of Early Dust Bowl Migrants | Grab a Hunk of Lightning

Published on Aug 14, 2014 – American Masters: Photographer Dorothea Lange and her husband were among the first to witness and to understand the causes of the huge migration to California in the 1930s: families were escaping the Dust Bowl. In this film excerpt, Lange talks about the first car she photographed before the country realized what was happening. American Masters’ Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning

What few people know is that Dorothea’s ability to portray the challenges of the human condition came from her own pain and infirmity. As a child she contracted polio, which left her with a withered foot. Each day, this petite little girl would walk alone on the streets of the Bowery on New York’s Lower East Side to meet her mother, who encouraged her to “walk as well as you can.” Dorothea would hide her limp and make herself, in her words, “unseen” — safe from unwanted attention. Resourceful and courageous, she transformed the lessons learned from her disability into an artistic strength. Later in life, Dorothea would say she “wore an invisible cloak” when approaching her photographic subjects so her presence would not influence them or the resulting images

Grab a Hunk of Lightning also explores the confluence of artists at work and in love. My grandmother had two major relationships: first her marriage to Maynard Dixon, the Southwest painter, and later her 30-year marriage to and collaboration with my grandfather, Paul Schuster Taylor. He was an unorthodox economist who insisted that field observation was more important than studying statistics at a desk. His specialties were migrant agricultural labor, the survival and importance of small family farms and, as corporate agriculture expanded, critical issues surrounding access to and fair use of water. From the first time Dorothea accompanied him (as his so-called “typist”) on a trip to study field labor conditions, their personal and professional lives entwined. Some of Dorothea’s greatest photographs came out of their rare creative partnership.

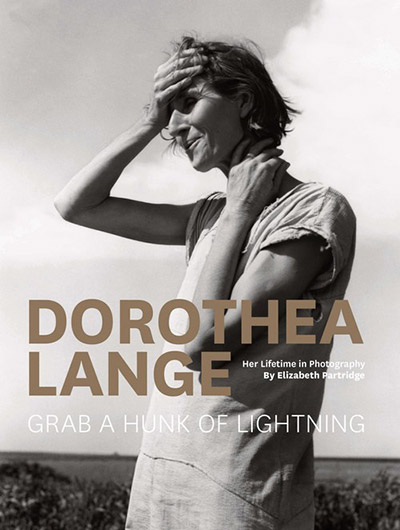

American Masters: A DVD will be available October 21, 2014, from PBS Distribution. The film features newly discovered interviews and vérité scenes with Lange from her Bay Area home studio, circa 1962-1965, including work on her unprecedented, one-woman career retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Showcasing more than 800 works by Lange, her first husband Maynard Dixon and second husband Paul Schuster Taylor combined, American Masters — Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning reveals the camera as Lange’s first muse and the confluence of artists at work and in love. Explaining the impact of these relationships on Lange’s life and documentary photography style, filmmaker/narrator Dyanna Taylor demonstrates the challenges of balancing artistic pursuits and family.

I have made a number of films about artists, their muses, struggles and vision, but it took me years to be ready to make this film. Before I could start, I needed a clear grasp of my grandmother’s impact, both positive and negative, on my personal life. At first, I had only my intimate childhood memories. Now, having completed my own journey of 10 years of extensive research, I feel able to present a balanced portrait of the public figure that was my grandmother. I’ve searched for Dorothea the woman through journals, diaries, family letters, negatives and footage, and expanded my understanding of her place in history and documentary photography through my conversations with scholars and artists. The resulting portrait is this film.

These days, everyone has a camera. What are we really seeing, trying to capture? As we enhance and alter photographs with elaborate techniques, I often wonder what Dorothea would say. Her images reveal her subjects with straightforward exactness. Her sense of the beauty in the unaltered truth of life stays with me. “See what is really there,” Dorothea always said. “Look at it. Look at it.”

The film’s companion book, Dorothea Lange: Grab a Hunk of Lightning by Elizabeth Partridge, is available now. The book can be purchased through Chronicle Books.

Presented by American Masters and WNET, Pulic New York Media

Text, images and videos approved for use by WNET, Public New York Media, 2014

Leave a Reply