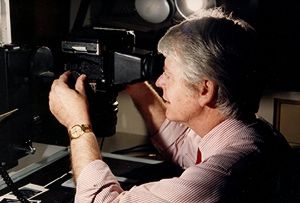

My name is Martin Golden, and I live and work in Denver, Colorado. At the risk of sounding like an old DRAGNET rerun, I carry a badge. You see, I’ve been a policeman for almost thirty years. The past eighteen years, I’ve been assigned to the Bureau of Laboratories working as a crime scene investigator and forensic photographer. My full title is Detective, but you can call me “Marty.”

My name is Martin Golden, and I live and work in Denver, Colorado. At the risk of sounding like an old DRAGNET rerun, I carry a badge. You see, I’ve been a policeman for almost thirty years. The past eighteen years, I’ve been assigned to the Bureau of Laboratories working as a crime scene investigator and forensic photographer. My full title is Detective, but you can call me “Marty.”

Photography is a vast field and has many related fields in which a living can be made. Forensics is as much a part of photography as fashion, freelance, or architecture. In Denver, which is the twenty-fifth largest city in the country, there are about four thousand forensic photos taken each year just for the Police Department, plus about fifty thousand identification photographs. There’s no end to job security!

What does it take to become a forensic photographer?

Over the years in my career, the question I’ve been asked most is, “How do you become a forensic photographer?” The question should be, “How can you become a cop?” As far as the cop job goes, you must know where all the sin is, yet not partake; work odd hours–including holidays; and spend most of your days off in court. You must school yourself (usually at your own expense) and study endless hours to keep up on new developments in the field.

I’ve been called upon to put myself at risk by photographing riots, documenting a homicide scene in a house full of poisonous snakes, photographing an accident scene with a high-pressure fire hose aimed at me (in case the vehicle burst into flame), as well as by fighting rats for possession of a victim. Yes, I’d do it again, if it means another bad guy gets convicted on the fruits of my labor. It’s well worth it.

Denver, as well as other jurisdictions across the nation, has been using civilian photographers for forensics instead of only police officers. In any event, whether you’re a cop or not, the main rule is the same: You must have a clean record. Among the civilian photographers in the field, no one would have any trouble passing an entry-level police test. In fact, many eventually do become officers.

How did forensic photography get started?

Historically speaking, forensic photography had its first case less than one month after photography was patented in 1839. Wouldn’t you know it, it was a divorce case! The plaintiff hired Louis Daguerre himself to photograph her husband and his girlfriend in front of the Paris Opera House. The court accepted the photograph (a Daguerretype) as evidence and awarded the plaintiff a divorce. (Incidentally, the court record and photograph were lost when they were destroyed by artillery fire during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870.)

As far as the American court system goes, photographs have been used since 1859, when they helped decide a Supreme Court case involving a runaway slave. The court ruled in favor of the runaway due to the injuries documented by the photograph.

EXHIBIT #1:

Forensic:(adj.) Belonging to, used in, or suitable to courts of law or open public discussion and debate.”

Thanks to Webster’s Dictionary, you now know more than the general public does about what “forensic” means. I’m particularly drawn to the “…open public… debate” part. “For anything, given enough time, can become forensic–even art; and anything forensic can become art.”

A prime example is shown below where a cave painting, which looks as though it was painted by Fred Flintstone, is one of the earliest art works in existence. This rendering done in the animal’s own blood is the center of a burning open public debate: Did early Man worship the animal this way, or was he merely trying to bring back the memory of a good meal with his picture? Or is the truth something else entirely?

EXHIBIT #2:

Likewise, the work I do can be seen as art.

EXHIBIT #3:

This is an unretouched photo of a fingerprint that shows either its owner’s sense of humor–or true, natural art.

Leave a Reply