by Rebecca Klein

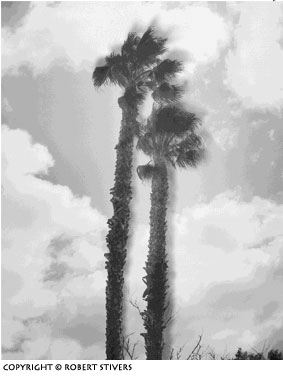

Robert Stivers is one of the best fine art photographers living today. His work is collected by museums from New York to Paris and Cologne and shown in galleries worldwide. His images sell for prices up to $6500. His career is going well. So, why is this artist, who has had so much success in one of the more difficult and coveted realms of photography, interested in pursuing the commercial world? For a man who started out studying the Science of Administration and ended up dancing with the Joffery Ballet – it makes perfect sense. That is the Ying and the Yang of Robert Stivers’ life.

What is a Good Man?

Robert Stivers’ life has been a dichotomy of commercial and artistic endeavors. Born into a family of scientists and corporate executives, he has lived more than a few lives trying to reconcile the psychological influences of his upbringing and the artistic aspirations of his soul. His father received his Ph.D. in civil engineering from Stanford and had a notable career as an aerospace engineer. His mother graduated Phi Beta Kappa and summa cum laude from Stanford and went on to be politically involved in California. “I’m the only one who, though later in life, took the artistic route,” Stivers says.

Stivers was born in 1953 in Palo Alto, California. Up until his graduation from UC-Irvine in 1976, he fulfilled the educational expectations of his family. Not long after entering a Masters program in the Science of Administration, he discovered a passion for dance, dropped out, and moved with his girlfriend to New York City. Within two years he was dancing with the Joffrey Ballet. But, his career in dance ended when he sustained a traumatic back injury in ballet class.

Caught in a downward emotional spiral after his injury, Stivers gravitated back to what he knew in hopes of regaining a sense of place. He became a licensed stockbroker/life insurance agent, but that career only accelerated the decline of his emotional state. He also earned a Masters at NYU in Arts Management and tried to run a dance company. “I thought that would be fulfilling,” he confesses. “It wasn’t.” After several more years of changing careers and also traveling through Europe, Stivers returned to L.A. where he met a couple of commercial photographers and became a self-taught rep. “I didn’t think I would actually ever pick up a camera myself. I just knew that I liked being around it. It was my introduction, through the back door, to photography.”

There is a Taoist saying about judgment that a good man is a bad man’s teacher and a bad man is a good man’s job. “Of the people I represented, one man in particular led me straight into bankruptcy because I put so much money into him but failed to ever get him work. But, he also taught me about photography, studio lighting, and printing. So ironically, I’m very grateful to him.” In the fall of 1987 Robert got serious about photography and took a workshop at UCLA under the instruction of famous art photographer Joanne Callis. Shortly thereafter, he quit repping.

“The events of my personal life and becoming a photographer are definitely related,” he says. “I didn’t choose to do photography because I thought I could make a living at it – I did it because I had to do it. It was a decision of, ‘this is my soul, this is my voice, this is my medium, and this is how I’m going to explore my relationship to the world, to the spirit, and to my life.'”

Since then, Stivers has rapidly emerged as one of the foremost contemporary photographers of our day. The fact that he started shooting at the relatively late age of 34 makes his accomplishments even more exceptional. Stivers’ work has been acquired by some of the most prestigious museums and institutions in the world. Among them are the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the L.A. County Museum of Art, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, The Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, and the Bibiliotheque Nationale in Paris. In New York, the galleries that have represented Stivers are the Throckmorton Fine Arts Gallery, the Yancey Richardson Gallery, and also Messineo/Wyman Projects in Chelsea, where he is currently on exhibition. Stivers has also produced two Monographs in three years, “Robert Stivers, Photographs” in 1997 and “Listening to Cement” in 2000, both published by Arena Editions of Santa Fe. Pentimento

Since then, Stivers has rapidly emerged as one of the foremost contemporary photographers of our day. The fact that he started shooting at the relatively late age of 34 makes his accomplishments even more exceptional. Stivers’ work has been acquired by some of the most prestigious museums and institutions in the world. Among them are the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the L.A. County Museum of Art, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University, The Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, and the Bibiliotheque Nationale in Paris. In New York, the galleries that have represented Stivers are the Throckmorton Fine Arts Gallery, the Yancey Richardson Gallery, and also Messineo/Wyman Projects in Chelsea, where he is currently on exhibition. Stivers has also produced two Monographs in three years, “Robert Stivers, Photographs” in 1997 and “Listening to Cement” in 2000, both published by Arena Editions of Santa Fe. Pentimento

In the galleries, Stivers’ work starts, unframed, at $1200 and goes up to $6500 for his large-scale prints mounted on anodized aluminum. “I make my living from the sales of my personal work,” he says. “I just bought my first home which is very exciting to me.”

While Stivers’ career is well established and his clientele strong, the commercial potential of his work beckons him like one of his own ghostlike images.

“I am interested in pursuing commercial photography simply because I like to explore things that are unfamiliar to me,” he says. “I’m very intrigued with the notion of recontextualization – giving my personal work a commercial application.”

n other words, having his existing images be used as a perfume ad, for example, or the cover of a book or music CD. “I don’t want to be precious about how my work is seen,” he says. “I think once the print is made it exists outside of me and it says something to somebody that I can’t argue with.”

Given his background in dance and developed understanding of the body and how it moves, it’s not hard to imagine Stivers crossing over to the fashion or music industry. I asked him what clients he sees himself shooting for. “I think they would have to be fairly enlightened,” he says seriously. “I’ve worked so hard in creating bodies of work, I can’t imagine anyone even approaching me unless they love what I do. The only difference between one of my images and the cover of a music CD or a fashion photograph is context.”

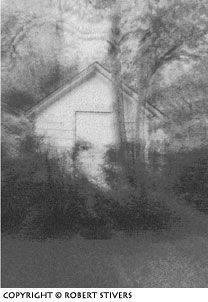

In his fine art career, Stivers’ images are as haunted as they are haunting. Like his own ghosts that never quite seem to settle, Stivers’ work continually reappears for him in shifting forms, tones, and meaning. “There’s a book that I’ve always assimilated into my life by playwright Lillian Hellman called “Pentimento,” which are reflections of her past. The word pentimento means “artist’s remorse” and is an art term for the process of painting over a picture many times over the course of many years until the original picture begins to show through,” he explains. “I think of photography in that way, which is why I like to explore old negatives. The meaning of my work shifts for me from day to day and even more so over the course of a few years when I have other work I can reference it to. I like observing how my early work bleeds through to the present. I see it as a metaphor for the layering of life and of how we paint over old experiences with new ones until our original experiences begin to show through.”

With his self-referential style, Stivers pays homage to memory, pain, and loss through his work while embracing renewal, change, and self-transformation. The results are darkly romantic, sensual, and erotic images bordering on aberrations. Stivers’ early work was especially emotive, raw, and visceral. His first body was a very direct and probing studio portraiture series of fellow dancers and friends. “It was an unleashing of sorts, like pulling my finger out of the dike emotionally,” he says. “It was primarily about the healing of myself.”

After a series of work inspired by artists such as Diane Arbus and Joel Peter Witkin, Stivers finally turned the camera directly at himself, creating a body of confrontational and powerful images that earned him his first artistic recognition. Among these early images are photographs of Stivers lying naked on a bed of nails pointing a gun at his chest, of himself drowning in a river wearing a straight jacket, and sitting with an erection holding a gun – symbolic of Stivers’ need to destroy his old self so that a rebirth could occur. “Stivers exposes his anxieties and desire for transcendence more poignantly than just about any other living artist,” writes John Stauffer, photo critic and professor of English, history and literature at Harvard University.

Series 5 In 1991, Stivers moved from Los Angeles to Santa Fe, New Mexico where he resides and works today. It was there that he completed Series Five, the body of work that solidified his reputation as a leading fine art photographer. “Series Five is probably Robert’s most profound body of work,” says gallery co-owner Helene Greenberg-Wyman of Messineo/Wyman Projects. “Especially his black and white gelatin silver prints of twisted and contorted bodies in which he really pushes the human form.” Series Five also marks the production of Stivers’ first monograph, “Robert Stivers Photographs,” as well as his break from straight photography. “Before Series Five I let all the drama unfold within the frame, using the negative as it appeared without cropping. With this body of work I began to allow what was initially on the negative to be transformed into something greater than itself,” he says. “The content of that work is still very much about self-exploration but is completely different visually from anything that came before.”

A prolific and ever evolving creator, Stivers moved from his acclaimed Series Five into his next body of work with an explosive, almost out of character expression of color.

“After working primarily in black and white silver prints for so long, I was ready to let the pendulum do its counter point. I worked in Cibachrome and let my palate of color go right off the charts with reds and blues, pinks, greens, and yellows – far beyond what my taste is really,” he admits. Many of the subjects in this series are preserved animals from the Museum of Natural History in New York. Somewhere between the cropping and intensity of color, his muses come alive in a startling semi-nightmarish reverie of brilliance. “A lot of these images come from black and white prints which I photographed with color transparency film and took into the darkroom to explore all over again.”

“After working primarily in black and white silver prints for so long, I was ready to let the pendulum do its counter point. I worked in Cibachrome and let my palate of color go right off the charts with reds and blues, pinks, greens, and yellows – far beyond what my taste is really,” he admits. Many of the subjects in this series are preserved animals from the Museum of Natural History in New York. Somewhere between the cropping and intensity of color, his muses come alive in a startling semi-nightmarish reverie of brilliance. “A lot of these images come from black and white prints which I photographed with color transparency film and took into the darkroom to explore all over again.”

After Stivers’ Color Series he embarked on a body of work that became his second book, “Listening to Cement.” With it, he began to work with different imagery, juxtaposing the human figure with architecture and elements such as water and clouds. “Anything that could symbolize the unconscious,” he says.

Stivers appears to be experiencing his own pentimento with his return to the human form in his latest body of work. “I’m back to where I began exploring myself vis a vis portraiture. My latest series, still in development, will include anything from eroticism to portraiture.”

The Fine Art of Alchemy

While several great commercial photographers have crossed over into fine art such as Helmut Newton, Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, going the other way is trickier business depending on the nature of the artist. “Right now we represent a commercial photographer who is doing his fine art work on the side,” says Greenberg-Wyman who has known and worked with Stivers for over a decade. “He is the flip-side of Robert, a different animal in many respects. He meets our deadlines like a trained seal. But Robert is the quintessential artist on all levels. He’s moody and temperamental. You can’t push him to deliver what you want,” she says, “you have to let him be.”

Greenberg-Wyman places Stivers among such well established and highly regarded photographers who have adopted a soft-focus approach as Adam Fuss and Bill Jacobson. “Robert comes from the school of pictorialist, as opposed to hyper realist, but, like Jacobson, he is more extreme and pushes the boundaries of that style,” Greenberg-Wyman explains. Stivers agrees that his work is not so neatly defined – pictorialism with a twist. “Unlike pictorialism, my work is much less idealized,” he says. “It’s less about romanticizing and more about mystifying.”

The mystification process of every Stivers’ piece is a timely and complicated one. “Robert is like an alchemist,” Greenberg-Wyman explains. “He uses lens based photography and handles materials flipping things back and forth – sometimes overexposing, sometimes underexposing depending upon what’s going on with him. Then he might re-shoot a print he’s already made and manipulate it further in the darkroom by enriching the tone of the gelatin silver print with more selenium or another kind of polytoner. That’s how he performs, like in a lab.”

Stivers’ magic does not occur in camera but by his hands in the darkroom – his images so manipulated that each one is a unique print. “The cameras I use don’t play an important part in my work,” he says. “I’ve only ever had an old Hasselblad 500 CM and lighting equipment that I bought used when I first began. I’m not very savvy with computers. The manipulation and transformation of the negative or transparency to a print happen in the darkroom. For today I really like getting my hands dirty, the craftsmanship, and the hands-on feel of making something. Although, like everything I do, I’m sure that will shift.”

Stivers’ Waking Dream

Regarding Stivers’ shift from the world of fine art into commercial photography, I asked him how he feels about working under the constraints of another’s ideas and deadlines. “To tell you the truth, the idea of that stresses me out a little bit. Working under my own pressure is pressure enough. It would be a tough challenge.” And if he were to be paid upwards of $30,000 for a nice day of advertising? “That could be some incentive,” he answers without hesitation. “But, my desire to work with a commercial client is not just about the money. It’s the idea of working with a client that loves what I do that excites me most. Ideally, I would like to have a client who gave me a certain amount of autonomy and let me do my thing. Now that would be fun.

“I have to feel passionate about and enjoy what I do,” Stivers adds. “When I fell in love with photography the way I had with dance, I realized I didn’t have to compromise. If commercial work made me miserable, it wouldn’t be worth the money for me. ”

“What links Robert’s fine art work to fashion is his exploration of the human form,” says Greenberg-Wyman. “I think Robert can bridge the gap to fashion if he wants to.” Considering the commitment and determination with which Stivers has embraced photography, and the amount of success he has acquired in a relatively short amount of time, anything is possible.

“I’m a great believer that anyone can accomplish whatever they are willing to show up for,” he says. “I still believe in 10% inspiration, 90% perspiration. I have been relentless in showing up for my work. And I think I’ve had to learn a lot of humility because it has been tough being older in this industry. Things don’t happen solely on their own momentum,” he says. “I am not passive in my career. I don’t wait for people to come to me or I would definitely have to have another job supporting myself.”

The completion of Stivers’ next series is imminent and he recently received a call from his San Francisco gallery saying that Edition Stemmle, a leading contemporary photography publishing house in Zurich, is interested in his work. How exactly his work will evolve from here depends on where in life Stivers finds himself next. “I let the work talk to me rather than me talking to the work,” he says. “And I think the work is beginning to tell me that I’m coming out of the reverie that I’ve been in for the last few years and coming more to a concrete conscious world.

by Rebecca Klein

Leave a Reply